The Music of Light: Emily Noyes Vanderpoel’s Colour Analysis Charts (1902)

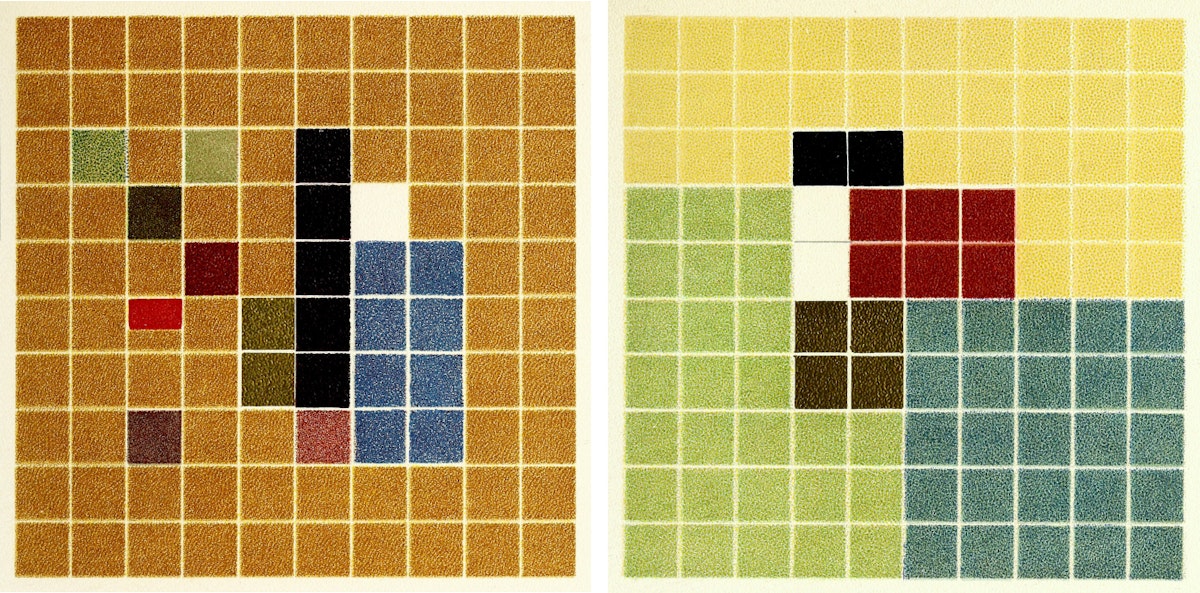

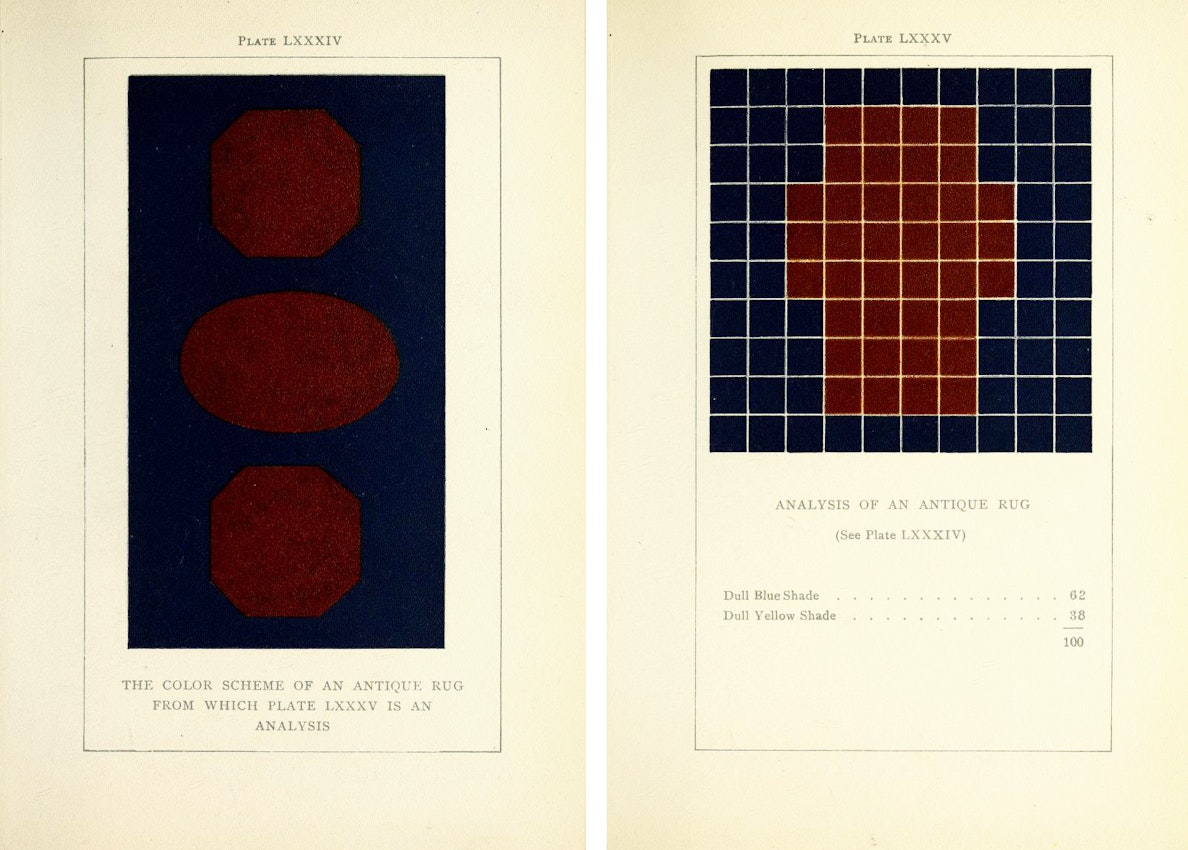

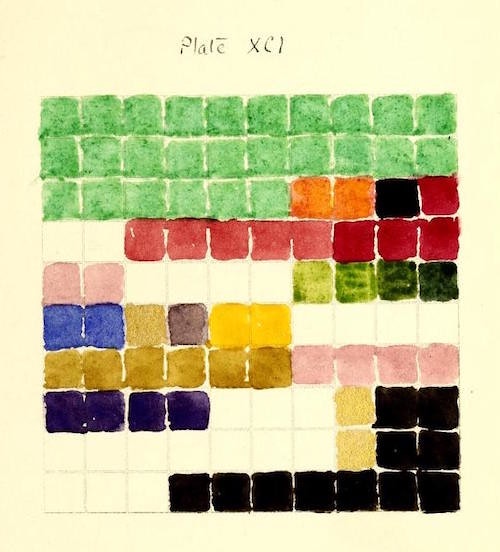

Looking at times like some kind of strange fusion of De Stijl abstraction and Tetris, these wonderful color charts are taken from Color Problems: A Practical Manual for the Lay Student of Color, a book by the American artist Emily Noyes Vanderpoel (1842–1939). Following her ruminations on color theory, she presents 117 plates featuring color analysis of various crafted objects, such as Assyrian tiles, Persian rugs, and Egyptian mummy cases, but also things from the natural world, including a stone and butterfly.

Vanderpoel does not explain in detail how her analyses were created. Instead, she simply places an image of an antique rug next to its abstraction, stating (with a fair degree of optimism) that from this example the student “will see how these and the other plates have been made”. Throughout Color Problems, Vanderpoel employs similar rhetorical maneuvers, splitting language off from the knowledge accessible through visual perception. As John Ptak notes, she “sought not so much to analyze the components of color itself, but rather to quantify the overall interpretative effect of color on the imagination”. Recognizing that “color cannot be fully appreciated by any written description”, Vanderpoel decides to keep her text “as brief as possible” and let the “full and elaborate” plates speak for themselves. Nevertheless, her writing offers a spectrum of poetic and scientific insights into color, which she calls the music of light. There are discussions of Chevreul, Goethe, and Ruskin; diagrams of how light enters the retina’s cones and rods; and lovely second-hand anecdotes: young women in Algiers, we are told, embroider with boxes of butterflies beside them, so that “from their harmonious blending of colors they may gain fresh enthusiasm and inspiration for their work.”

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Vanderpoel’s grids are best understood as relational fields. In her appendix, she defines her technique as “a systematic arrangement of colors in a geometrical design such that every variation and combination of hue, tint, and shade is in its proper place and in correct relation to all other hues, tints, and shades.” While it remains somewhat opaque what exactly she deems proper and correct, this “systematic arrangement of colors” not only anticipates later abstractions in the visual arts, but seems abreast of her modernist contemporaries’ experiments with relational systems. In a way, Vanderpoel did for light what Gertrude Stein would do for language twelve years later in Tender Buttons, which begins with a description that echoes Vanderpoel’s own: “an arrangement in a system to pointing”.

Vanderpoel ends her 122-page treatise by widening her focus on “harmony” from an artistic practice that happens on the easel to a way of being in the world:

No woman has a right to say she has no influence, conscious or unconscious, on the world around her. Does not much of the influence for good or ill come from a woman’s dress? It may be cheap, it may be plain, but it should be, and can be, in good taste and harmony with the character and position of the person who wears it, and knowledge of one’s own coloring and of that suited to it is one of the most important details.

Published when Vanderpoel was fifty-nine years old, Color Problems, as the subtitle implies, was aimed at the amateur colorist — not artists, but decorators, shop assistants, and gardeners: all who could improve their lives and crafts with attention to the complementary aspects of color. She believed that every gradation of light leads back to nature, and agreed with F. W. Moody that “There is hardly anything in nature that is not perfect in color. A dead sparrow would enable you to arrange the marquetrie of a cabinet with faultless harmony.” As in her discussion of feminine dress above, Vanderpoel sought to further democratize who was “bidden to go to nature for the abundant secrets she is ready to reveal”, asking that “workers” be sent to the same fount of inspiration that students in art and science seek out.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Although she wrote other critical works on art, such as American Lace & Lace-Makers (1924), Vanderpoel was, for a long time, better remembered for her artworks — she primarily worked with watercolors and oils, and held the position of vice president of the New York Watercolor Club — and for her historical writing, until a recent revival of interest in her color analyses. She was the first curator of the Litchfield Historical Society, writing a two-volume history on the town’s Female Academy, titled Chronicles of a Pioneer School. Out of print for more than a century, Color Problems was recently republished by The Circadian Press in a beautiful new edition (sadly sold out). Also check out this digital tool for generating Vanderpoelian analyses from your own images, and this related color bot, automated by Liza Daly, inspired by our original post on Color Problems.

Imagery from this post is featured in

Affinities

our special book of images created to celebrate 10 years of The Public Domain Review.

500+ images – 368 pages

Large format – Hardcover with inset image

Mar 15, 2016