In Search of the Third Bird Kenneth Morris and the Three Unusual Arts

In his ecstatic poem of rebirth, “Starting from Paumanok,” the great bearded bard of mad beauty and love-bombast, Walt Whitman, suddenly calls out to the past: “And you precedents!” he cries, calling for their attention. What does he want from them? He wants those “precedents” to “connect lovingly” with his own work, his own creations, his poems. In one sense, this is odd. The stuff of the past cannot embrace us, or the things we make. It is dead. But in another sense, the longing that the embrace with history should be mutual is by no means insane. In the essay that follows, Easter McCraney (who is not insane) arranges for just such a mutual embrace. The result is disorienting. But, in its way, full of truth. It is the truth of a poem, which is always the product of the labor of a reader who works with a rich and redolent (if also, generally, ambiguous) text. In this sense, Easter has written a kind of history-poem.

— D. Graham Burnett, Series Editor

September 7, 2016

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Reginald Machell's highly allegorical painting The Path (ca. 1895), which was used as the cover of the Theosophical Path for many years — Source.

The Theosophical Path (1911-1935), formerly called Century Path, was one of a number of periodicals edited by Katherine Tingley (1847-1929) during her tenure as head of the Theosophical Society in the United States. Its readership comprised, but was not necessarily limited to, those in residence at Lomaland, the Theosophical community at Point Loma, California, founded by Tingley in 1900, and first conceived as a School for the Revival of the Lost Mysteries of Antiquity.

The SRLMA included a “Raja-Yoga” school, where young boarders of diverse backgrounds were grouped into “Lotus Houses” and given comprehensive training in the arts of the human mind, body, and spirit, in keeping with the final perfectibility of humankind and the ambition of universal excellence. A latter day chronicler provides a suggestive and compact explanation of the mission of the Lomaland school:

To grasp the guiding principles that determined the policies and programs of the Point Loma schools, it is necessary to understand the term raja yoga, the “royal or kingly” method used in the eternal battle of the human soul to control its weaknesses and earn its way to union with its inner god. Students on this path must become aware of the inner god that is their teacher, and of the body as the temple of the spirit, to be kept strong and fit. They must learn that the gentle promptings of the divinity within are best recognized in moments of silence and attentiveness.1

On the verdant Lomaland grounds and in its atria and auditoria, students performed the works of Aeschylus and Shakespeare, learned musical instruments, raised crops, baked bread, studied the minute wonders of nature, and practiced self-sufficiency. The Lomaland press, as well, with the help of its photo and engraving department, produced many periodicals for both adults and children over the lifetime of the community, full of instruction and optimism for the future, often in the pedagogically earnest tone of one’s maiden piano teacher assigning finger exercises.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.The buildings and grounds of the Raja Yoga Academy at Point Loma, ca. 1915 — Source.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Children at Raja Yoga Academy, Point Loma, ca. 1915 — Source.

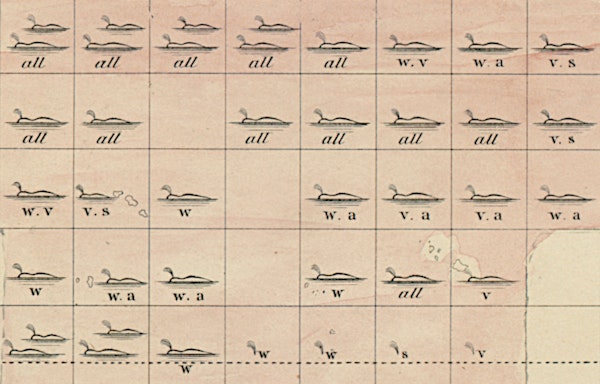

In the October 1916 issue of The Theosophical Path appears an essay titled “The Birds of Lomaland”. The piece is oddly placed — amid articles on the tripartite structure of the human soul and the freedom of the will — enough that it seems, for all its good cheer, to demand a suspicious reading.

Its author describes the beauties and behaviors of birds commonly found on the Lomaland grounds, from the California towhee to the housefinch to the Brewer’s blackbird. However, certain twists of expression lead the reader to suspect that in fact specific people in the Lomaland community, not their feathered friends, are being allusively described. The very scrupulosity of the descriptions shadows them with double entendres. One bird — a colleague whose eccentricities are fondly known to the magazine’s readers? — is a “pitiless tyrant to one who has once come under his sway”; he is prone to display a “simulated anger” with his “wife”, but to either her sorrow or glee, he is “never happier than when rustling about under the protective branches of some low-growing shrub”. Startling set pieces abound as well, particularly those describing the behavior of the Lomaland birds in groups. An array of goldfinches descends upon a “dead weed”, for example, in a strangely “undulating flight and a chorus of low twittering” that recalls a ritual dance of temporary resurrection.

Were it not for a further network of clues and allusions scattered throughout the remainder of this particular October 1916 issue of this humble publication, one would have to leave things here — since there is only so far that one can spin stories and speculations about birds. But traces of a deeper, or at least an other, meaning are clearly discernible to the interested eye, particularly in their relation to a writer, amateur historian, and Theosophist by the name of Kenneth Morris (1879-1937), who lived and taught at Point Loma for two decades, from 1908 to 1929. Though Morris’ work is still anthologized and reprinted from time to time, quite nearly his entire oeuvre played itself out on the pages of the various Point Loma periodicals edited by Katherine Tingley, to be read by members of the Lomaland community or by committed Theosophists, and survives largely, if at all, in the archives of the American branch of the Theosophical Society now located in Pasadena.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Portrait of Kenneth Morris, date unknown — Source.

In this issue of The Theosophical Path, however, Morris is ubiquitous. He is the author not only of one short, impassioned poem titled “Mater Implacabilis” and an article on Islamic history titled “Golden Threads in the Tapestry of History”, but also a Taoist parable, “Red-Peach-Blossom Inlet”, under the pseudonym Hankin Maggs. Morris, who was fond of pseudonyms, may easily have been responsible for other pieces in the issue as well. And even if the “Percy Leonard” who composed the “Birds of Lomaland” feature, for example, is most likely identical to the better-known Theosophical writer H. Percy Leonard, might Morris have had a hand in its composition or editing? It may be significant in this regard that a 1912 issue of the Tingley-edited Lomaland youth publication Raja Yoga Messenger, which also heavily features Morris’ work, also contains an article titled “The Birds of Lomaland” (this time by a “Cousin Edytha”), which cryptically notes that “Lomaland is getting to be a real bird land”, and that birds “have not hesitated to build [nests] right under our very noses, so to speak”.

More tellingly, and more than once in the Messenger, a piece by Morris is preceded or followed by one with birds somewhere in the title — in one case (March 1914), “The Bird as Omen”. The Raja Yoga Messenger also printed Morris’ story “Sion ap Siencyn”, which bears a strong resemblance in structure and theme to “Red-Peach-Blossom Inlet”.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Illustration for Morris' "Red-Peach-Blossom Inlet", featured in the October 1916 issue of The Theosophical Path — Source.

The latter concerns a young man who abandons the world of ambitious “cheaters and thumpers” to seek tranquility and inner peace. But even his favorite meditative activity, fishing, is too much a cause of distraction, and he can only continue it after carefully straightening his fish hook. (One cannot but see Morris himself, patiently straightening his own literary hook, renouncing fame, pursuing his own spiritual ends.) One day, adrift, and quite by accident, the fisherman discovers the realm of the immortals. But he is cast out of paradise — or casts himself out — at the moment he wishes to see his enlightenment and his perfected state reflected and registered in the world of ambition that he has abandoned. “Sion ap Siencyn” is the story of a man who wanders into the realm of Rhianon (or Rhiannon, more commonly), a figure of Welsh myth, and encounters the so-called three “Birds of Rhianon” which, though mentioned in the Welsh source material with which Morris was deeply familiar, are in their greater detail entirely his invention. One encounters them in “Sion ap Siencyn” — but also elsewhere, as we see below — as the white bird of pleasure and cease of sorrow; the blue bird of transfiguration; and the rainbow bird of wisdom and wonder.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Note the bird that features in this image depicting a state of close, even trancelike attention, from “Sion ap Siencyn” in Raja Yoga Messenger (July 1921) — Source.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

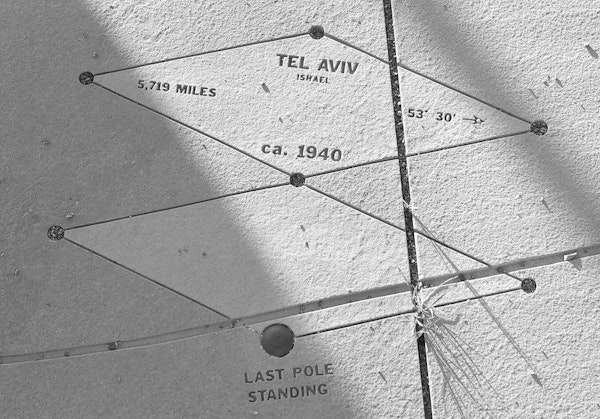

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.An image of a bird also appears at the end of the story, accompanied by “Wise Sayings” — Source.

Morris’ third text in this issue of The Theosophical Path (or fourth, if the “Birds of Lomaland” are as much his own confection as the revised Birds of Rhianon), “Golden Threads in the Tapestry of History”, is an account of the alleged betrayal of the true and “inner Islam” by those who elected the Prophet’s father-in-law Abu Bakr leader of the faith instead of his cousin and son-in-law Ali the “Lion of God”. (This approach, to say the least, begs a number of rather fraught questions, as current events will attest.) The article locates a “true” Islamic strain oddly congruent with the salient doctrines of Theosophy — these being “reincarnation, the divinity in man, the existence of a secret school of Initiates, and their appearance as Teachers from age to age among men”.

One of the doctrines of Theosophy is that the human heart is “godlike in its higher aspects” — and only in its godlike aspects is it able truly to hear the subterranean roar, like a “heartbeat”, of the river of Sacred Truth as it “plunges into its caverns measureless”, beneath the well-mapped hills of history. This special sense of hearing is something, perhaps, like the averted, peripheral vision that allows one to glimpse the fainter, more distant stars, for esoteric truths can only be glimpsed, never directly verified. The Prophet, writes Morris, “never preached Theosophical doctrines at large [...]. No; or they would have ceased to be esoteric.”

As far as history itself is concerned, Morris begins his essay by assuring the reader that “we are not concerned here with history ‘as she is wrote’ by omniscient western pundits; omniscience is always a bore, especially when it deals in negations”. The historian’s task is to:

be prepared to venture boldly: using intuition and imagination; directed by a splendid faith at all times; tied down by no limitations of the brain-mind, nor hoppled with quidnuncs and quiddities [...] boldly reject whole volumes of apparent evidence; which is the most tricky thing in the world, and can be forged liberally or buried wholesale.

History, Morris concludes, is simply a kind of “jugglery”. What he demonstrates is that Theosophy, in order to follow its own golden thread through history, must first loosen it up, like an icebreaker pushing through sea ice. Historical matter is neither created nor destroyed, only displaced, jostled, buckled, set adrift.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Bird logo, from Raja Yoga Messenger (January, 1920) — Source.

What we have here, in summary, is a morsel of historical matter which, in its esoteric obscurity, might as well be invented — in the form of an issue of a Theosophical magazine intended for the brothers and sisters of a long-dissolved utopian commune, dominated by a single author using one or more pseudonyms, and concerned not only with the means of discerning an other world within our world, and an other history within our history, but featuring birds (rather, “birds”) performing strange rituals, rapt before the Fields of Being. But what of it, really?

Suffice it to say that it is my belief, as part of the research consortium known as ESTAR(SER), that Kenneth Morris was either a member of, or otherwise affiliated with, the highly secretive, fugitive, acephalous body of practitioners known as the Order of the Third Bird, the submontane passages of whose history ESTAR(SER) exists to map and indeed to forge; and that Morris, with or without Tingley’s knowledge and involvement, was using this issue of The Theosophical Path — and possibly other issues, and other Lomaland publications — to address members of the Order who were constellated throughout the Point Loma community, like a hidden nerve system. It is likely, consulting the existing (though sparse) literature, that there was already a high concentration of “Birds”, as members of the Order call themselves, in the United States Theosophical community — especially given the strong arguments for this being the case regarding the Theosophical Society headed by Henry Steel Olcott and Annie Besant based in Adyar, India.

The facts remain, as they perhaps must, slippery and treacherous, as ice floes that dip and plunge. But incrementally and over decades of steady endeavor by the researchers of ESTAR(SER) and occasionally by others, it has become clear that the Order of the Third Bird has existed for some period of time, and that it has a propensity to multiply itself, constantly sending out new shoots and branches, as well as a tendency to appear where it is least expected — and always, for that matter, where it is most expected. Its influence, silent where it runs deepest, is most often discernible only in those hints and traces which it has been the habit of ESTAR(SER) to decipher, eyes slyly averted to catch their dim signal. But while ESTAR(SER)’s historical speculations and archival reconstructions often remain, for lack of sufficient documentation, just that, practitioners of the Order can also be seen today, in any museum or street, standing completely still in groups of four or five, swatches of telltale saffron peeking from pockets and belt loops, their gazes formidably, unwaveringly fixed on a single object, most often a work of art.

Although here is not the place to fully lay out what is known of the Order and its practices in all contextual fullness — since more always remains to be said — a few basics can be established. The Order derives its name from one of the fragmentary epyllia ascribed to the fourth-century Latin rhetorician Ausonius, an embellished retelling of Pliny’s well-known story of Zeuxis and the painting of the child carrying grapes. Pliny recounts the great painter’s frustration that birds pecked at the fruit in the picture, since he took this as proof that the boy was less well executed than his harvest: “if I had done a better job on the figure”, he declares, “the birds would have been too frightened to approach”. The pseudo-Ausonian prose translation continues as follows:

It is said that Zeuxis went back to work on the painting, in the hopes of improving the child, and that when he put this new work outside to dry, he hid himself in the bushes to watch. And we are told that he saw three birds approach. One, making for the grapes, seemed suddenly to notice the boy and flew off with a squawk. The second, similarly drawn to the fruit, disregarded their guardian entirely, and pecked furiously at the illusory meal. But the third stopped before the tablet and stood in the sandy courtyard, looking fixedly at the image, and seemingly lost in thought. “What a curious bird!” mumbled Zeuxis, but the bird did not move.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Engraving depicting Pliny's tale of Zeuxis and Parrhasius, from Den gulden winckel der konstlievende Nederlanders (1613), a book by Joost van den Vondel — Source.

This story famously reflects the central preoccupation of the Order, which is to collectively engage in practices or “protocols” of sustained attention and “practical aesthesis” upon works of art and/or other material phenomena made to be seen (though this last phrase is often open to interpretation). The very simplicity of its aim is what gives rise to the great cornucopia of experiential, social, and metempsychotic exercises and traditions that compose the Order’s history.

Little in Morris’ life story directly points to his affiliation with the Order. Kenneth Morris came to Point Loma originally from Wales, but a detailed biography on the website Daily Theosophy indicates that Morris first encountered Theosophy as an adolescent abroad in Ireland, where he “joined a group of the most prominent Irish thinkers and authors of these days, among which were Standish O’Grady, Æ, [and] William Butler Yeats”. Around this time he also began to write poetry and short stories, all of which were published in Theosophical periodicals. His prior interests in Celtic myth and tradition secured his growing devotion to the cause, and only a year after he met Katherine Tingley, he settled at Lomaland for what was nearly the rest of his life (he returned to Wales only when she died) giving lectures on Celtic literature at the Raja Yoga School. He also began work, soon after he arrived, on a retelling of part of the thirteenth and fourteenth-century Welsh myth cycle known as the Mabinogion. Titled The Fates of the Princes of Dyfed — and inspired by his Theosophical faith as well as by the sui generis, druidic “scriptures” of the great Welsh antiquarian and forger Iolo Morganwg (1747-1826) — it was first published in 1914 by the Theosophical Press at Point Loma, and reissued in 1978 as part of the Newcastle Publishing Co.’s Forgotten Fantasy series, alongside works by Lord Dunsany, H. Rider Haggard, and William Morris.

It is not the details of his life, as it turns out, but a further reading of his oeuvre — a reading, specifically, of The Fates of the Princes of Dyfed — that threatens to transform the teasing out of esoteric meanings into the laying forth of exoteric fact. For it is here that Morris tells his tale of three birds, in the section titled “The Story of Rhianon and Pryderi, or The Book of the Three Unusual Arts of Pryderi fab Pwyll”. The second, five-part “branch” of this section is devoted specifically to the freeing of the imprisoned Birds of Rhianon by a young man named Gwri Gwallt Euryn, who does not yet know that he is Prince Pryderi, the son — abducted at birth — of Rhianon herself. What he does know, however, are the three “Unusual Arts” taught him by his mentor and guardian Teyrnion (or Teyrnon): the art of war in the midst of peace; the art of peace in the midst of war; and the spell of the wood, the field, and the mountain. He will use these arts to locate and liberate the three birds, who are named Aden Lanach, Aden Lonach, and Aden Fwynach.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

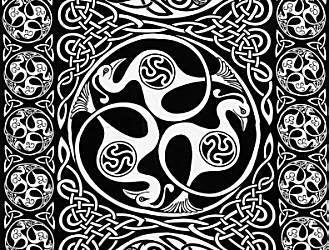

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Modern image by the artist Jen Delyth — Source (not public domain).

The interlocking and — to borrow a term from Celtic art — triskelionic structure of Morris’ narrative is as complex as that of his source material, and its recursive patterns are densely colored with Theosophical allegory. The nature of the three birds and the circumstances of their liberation, however, can be described in basic outline as follows. The First Bird of Rhianon, Aden Lanach (also simply Glanach) is white as “the color of the sunlight on the snowflake”, and her singing is “awakenment, and the passing of sloth into valor”. She is imprisoned in a fortress guarded by deeply slumbering giants, whose time has come to be rudely roused by the first Unusual Art, the art of war in the midst of peace. The hero, Gwri, quite literally teaches them warfare — and as their “valor” increases, the First Bird awakens and recovers her song.

The Second Bird of Rhianon, Aden Lonach (also Llonach) is “the color of the blue forget-me-not in the marshland”, and her singing is “a coolness upon all aching, and the passing of desire into peace”. She is held hostage amid a great host making uproarious warfare; unlike her sister, she begins to wake and sing as the sound of the sharpening of weapons, drawn out and nuanced in Gwri’s adroit hands, becomes music. This is the second Unusual Art, the art of peace in the midst of war.

As for the Third Bird of Rhianon, Aden Fwynach (or Mwynach) “there are better colors on her wings than in the rainbow”, and her singing is “the passing of the heart from its bondage, the fulfillment of the ultimate concerns of the soul”. She languishes in the Castle of Caer Hedd, a place of great feasting, heavy enchantment, and the spinning of gorgeous falsehood. Lost amid twittering throngs of beautiful birds, Mwynach has forgotten who she is, and the castle inhabitants claim never to have heard of her. The king of the Castle attempts to regale and distract Gwri with food, drink and story; to these three temptations in turn, Gwri responds with the three parts of the last Unusual Art: the Spell of the Wood, the Field, and the Mountain. The names of these “three places in Wales” have power to dissipate the mists of pleasant falsehood and specious pleasure. When the king, as a last measure, hands Gwri a harp, hoping the latter might ensorcel and beguile himself with the sound of his own singing voice and the charm of his own fictions, Gwri sings instead of the Third Bird, and of her troubling absence and silence. It is this song, finally, with each successive verse, that brings her fully to life and remembrance.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Artwork from Morris' The Fates of the Princes of Dyfed (1914) — Source.

The basic ritual, or “protocol”, of sustained attention in universal use among practitioners of the Order of the Third Bird consists of three primary phases, which are called (with small variations) Attending, Negating, and Realizing.2 Rather than the three birds of Morris’ allegory corresponding, as one might expect, to the first, second, and third bird of the aforementioned pseudo-Ausonian parable, it seems they correspond to these three phases, in which practitioners ask in turn, of the Work before them, What Is, What Is Not, and What Shall Be. Attending — like the song of the First Bird of Rhianon and like the first Unusual Art — is a phase of awakening, to all that is before one and all that is — in which, also, what is immediately before one becomes all that is. Negating — like the song of the Second Bird of Rhianon and like the second Unusual Art, and like sleep — undoes all that is, and undoes those aspects of the self that greet and desire what is. Realizing — like the song of the Third Bird of Rhianon and like the third Unusual Art — is a phase of fulfillment, in which the inherent potential of what is breaks free in an act of paraphysical bardsmanship (or birdsmanship) that resembles storytelling, but is also the process by which storytelling becomes reality.

It is possible, in the end, that these mere comparisons and congruencies fail to convince. One wonders, for example, whether threes and birds — not to mention awakenings and realizations — are not simply native to Theosophy and to the spiritual traditions from which it draws. (Take, for example, the term Kalahansa — one name of Brahma and Sanskrit for the “swan of time”. As the First Cause of the universe, from this “Great Bird” emanate Three Logoi, moving from formless void to dawn to the light of consciousness.3) In this case it is not beyond possibility that practitioners of the Order, always syncretist opportunists, drew inspiration from Theosophy — but also that the twentieth-century practice of Theosophy, especially in the United States, drew inspiration from the Protocols of the Order. More research is needed.

Easter McCraney is an affiliate researcher with ESTAR(SER).

![[*Door creaks open. Footsteps*]: Fredric Jameson’s Seminar on *Aesthetic Theory*](https://the-public-domain-review.imgix.net/essays/mimesis-expression-construction/5448914830_cc288c2266_o.jpg?w=600&h=1200)

[Door creaks open. Footsteps]: Fredric Jameson’s Seminar on Aesthetic Theory

By meticulously translating his recordings of Jameson’s seminars into the theatrical idiom of the stage script, Octavian Esanu asks, playfully and tenderly, if we can see pedagogy as performance? Teaching and learning, about art — as a work of art? more

Chaos Bewitched: Moby-Dick and AI

Eigil zu Tage-Ravn asks a GTP-3-driven AI system for help in the interpretation of a key scene in Moby-Dick (1851). Do androids dream of electric whales? more

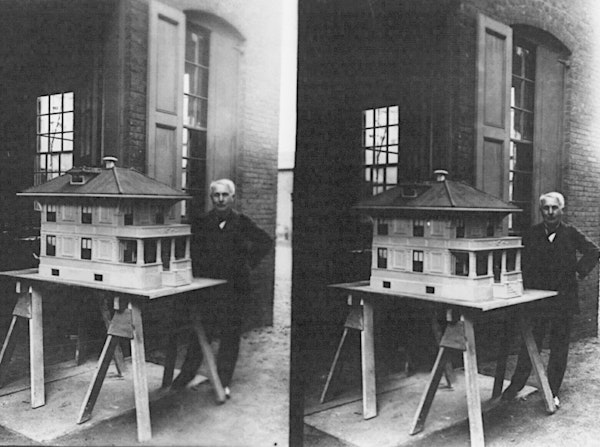

Concrete Poetry: Thomas Edison and the Almost-Built World

The architect and historian Anthony Acciavatti uses a real (but mostly forgotten) patent to conjure a world that could have been. more

In the affecting work of sensory history, Peter Schmidt uses the “strikethrough” as a kind of shadow-writing: his “Encyclopedia of Light” reveals little dark threads of undoing — marks of the second thought that endlessly cancels the first. more

Brad Fox tells a history-story that pulls on a life-thread in the tangle of things. But that only makes it all a little knottier, no? more

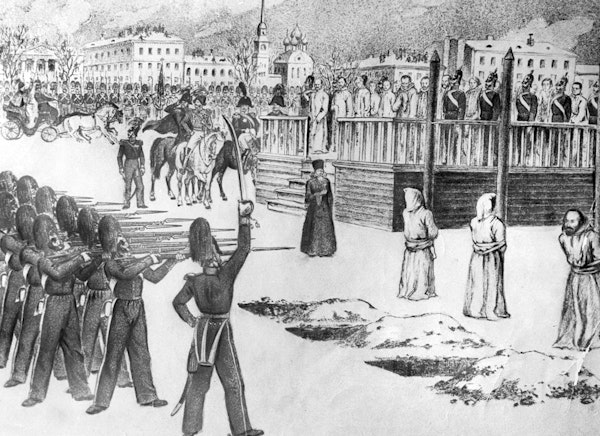

A second life? To live again? Fyodor Dostoevsky survived the uncanny pantomime of his own execution to be “reborn into a new form”. Here Alex Christofi gives these very words a kind of second life, stitching primary source excerpts into a “reconstructed memoir” — the memoir that Dostoevsky himself never wrote. more

In this affecting photo-essay, Federica Soletta invites us to sit with her awhile on the American porch. more

.jpg?w=600&h=1200)

At the intersection of surfing and medieval cathedrals, from the contents of a suitcase, Melissa McCarthy stages a plot that walks its way across paranoia, language, and the pursuit of knowledge. more

Food Pasts, Food Futures: The Culinary History of COVID-19

A criti-fictional course-syllabus from the year 2070 — a bibliographical meteor from the other side of a “Remote Revolution”. more

Titiba and the Invention of the Unknown

In this lyrical essay on a difficult and painful topic, the poet Kathryn Nuernberger works to defy history’s commitment to distance, to unsettling effect. more

In Praise of Halvings: Hidden Histories of Japan Excavated by Dr D. Fenberger

Roger McDonald on the mysterious Dr Daniel Fenberger and his investigations into an archive known as “The Book of Halved Things". more

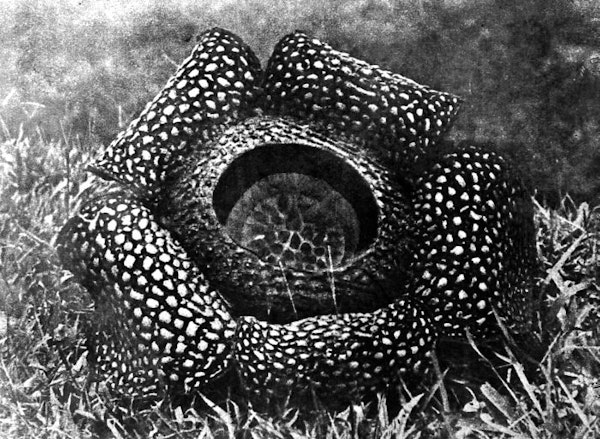

Weaving extracts from a naturalist’s private journals and unpublished sci-fi tale, Elaine Ayers creates a single story of loneliness and scientific longing. more

Remembering Roy Gold, Who was Not Excessively Interested in Books

Nicholas Jeeves takes us on a turn through a Borgesian library of defacements. more

Kant in Sumatra? The Third Critique and the cosmologies of Melanesia? Justin E. H. Smith with an intricate tale of old texts lost and recovered, and the strange worlds revealed in a typesetter's error. more

Lover of the Strange, Sympathizer of the Rude, Barbarianologist of the Farthest Peripheries

Winnie Wong brings us a short biography of the Chinese curioso Pan Youxun (1745-1780). At issue? Hubris, hegemony, and global art history. more

The Elizabeths: Elemental Historians

Carla Nappi conjures a dreamscape from four archival fragments — four oblique references to women named “Elizabeth” who lived on the watershed of the 16th and 17th centuries. more

Dominic Pettman, through the voice of a distant descendant of the Roomba, offers a glimpse into the historiographical revenge of our enslaved devices. more

Every Society Invents the Failed Utopia it Deserves

In a late 19th-century anarchist newspaper, John Tresch uncovers an unusual piece, purported to be from the pen of Louise Michel, telling of a cross-dressing revolutionary unhinged at the helm of some kind of sociopolitical astrolabe. more