“Though Silent, I Speak”: A Book of Sundial Mottoes (1903)

When thought needs a muse, it claims an evocative object. Long ago, love found hearts; secrets found keys; discovery found light; change found rivers. For many centuries this list would have had to include time finding sundials. Even the earliest sundials were inscribed with text, suggesting that a sundial was always both a way of telling time and a focal point for reflecting on its nature. Time has no voice, but sundial inscriptions pretend otherwise.

In 1737, Charles Leadbetter published an instructional book called Mechanick Dialling: or, the New Art of Shadows about how to build a sundial. He included a selection of three hundred mottos, of which, he suggested, builders should choose one as the finishing touch on their project. The mottos were a small part of Leadbetter’s book, but as sundials entered their twilight of obsolescence, the mottos took on a life of their own. Other sundial enthusiasts began assembling and publishing collections of inscriptions, and reprinting Leadbetter’s. The task had a poetic hook: What can we learn about time from a timekeeping device made obsolete by its passage?

Several books were ultimately published, among them Alfred H. Hyatt’s 1903 A Book of Sundial Mottoes. Hyatt selected sixty inscriptions, all drawn from Leadbetter, to which he added various quotes about sundials from famous writers, and his own ode-like introduction. It’s a small gift-type book, geared toward gardeners — sundials had by then become part of English country garden design.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

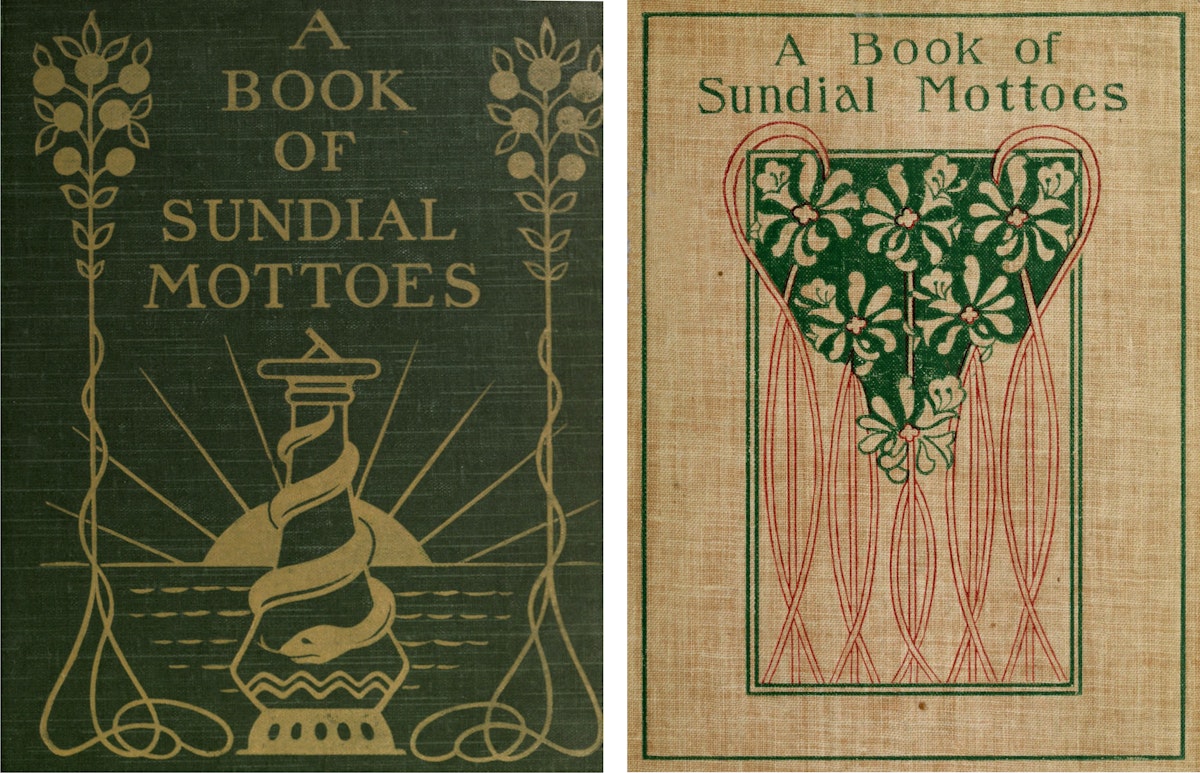

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Front covers of two 1903 editions of Sundial Mottoes

The book is awash in nostalgia, but the mottos less so. Most are bracing and hawkish. “This Dial Says Die”, for instance, makes the reader sit up straight, as does “Either Learn or Go”. Others deliver solid, if terse, advice, for example: “Do Today’s Work Today” and “Learn to Value Your Time”.

A few are inscrutable, at least to this reader. “The Time Thou Killest Will in Time Kill Thee” might be a reference to harmful leisure habits, or it could darkly refer to all time, wherein time passed while living equals time killed. I was perplexed by “Opportunity has Locks in Front and is Bald Behind”, until my editors pointed out that the aphorism condenses a longer proverb, about Opportunity’s distinctive hairstyle. (“Opportunity has hair in front, behind she is bald; if you seize her by the forelock, you may hold her, but, if suffered to escape, not Jupiter himself can catch her again.”) Sundial advice is usually dispensed as generic wisdom, but occasionally the speaker reveals himself. One patriarch used his sundial to wag a finger at his progeny: “Remove Not the Ancient Landmark which Thy Father Hath Set Up.”

The eeriest sundial inscriptions are written in the first person, as if the sundial is ventriloquizing time itself. What sorts of things does time say? Mostly ominous, haunting things, what one might expect from a hooded ghost with a scythe, not a sundial in an English country garden: “Look Upon Me. Though Silent, I Speak. For the Happy and the Sad, I Mark the House Alike. I Warn as I Move. I Steal Upon You. I Wait for None.” And also, stop looking at this sundial and get on with your life: “Begone About Your Business.”

Apr 25, 2023