In Hollywood with Nathanael West

Today the works of Nathanael West enter the public domain in many countries around the world. Marion Meade, author of Lonelyhearts, a new biography about West, takes a look at his life in Hollywood and the story behind his most famous work, The Day of the Locust.

January 1, 2011

Hollywood has served as a novelist’s muse for almost a century. The list of writers who found inspiration there includes the likes of Fitzgerald, Mailer, Schulberg, Bukowski, Chandler, Huxley, Waugh, and O’Hara, among plenty of others. But the gold standard for Hollywood fiction remains The Day of the Locust.

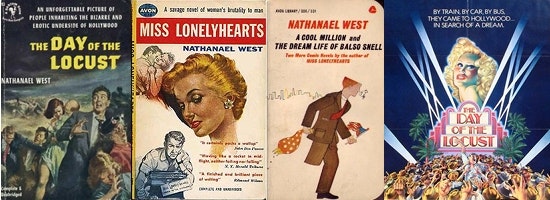

Nathanael West—novelist, screenwriter, playwright—was one of the most original writers of his generation, a comic artist whose insight into the brutalities of modern life would prove remarkably prophetic. In addition to The Day of the Locust he is the author of another classic Miss Lonelyhearts (1933) as well as two minor works, The Dream Life of Balso Snell (1931) and A Cool Million (1934).

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Seventy years after publication, The Day of the Locust is still the most significant novel ever written about Hollywood. Beyond that, West’s story examines America during the Great Depression, revealing a diseased country being stained by corruption, hypocrisy, greed, and rage.

Movie stars who get their faces on the screen did not excite West. Neither was he dazzled by Hollywood as the glitz and glamour capital of the world. Instead, his tale goes backstage to focus on the raw inner workings of a byzantine business and the working stiffs who write scripts, design sets, and appear in crowd scenes.

In the novel’s opening scene, a mob of fake infantry and cavalry is being herded away to fight the fake Battle of Waterloo.

“Stage Nine—you bastards—Stage Nine!” a second unit director shouts hysterically through his megaphone.

West’s heroes are the cheated ones dredged up from the sea of extras and bit players, the menial assistant directors and lowly writers.

Buzzing in the background, meanwhile, are the locusts, the plagues of angry migrants disconnected from Middle America, seduced by the promise of California sunshine and citrus. (The Grapes of Wrath showcases some of the same displaced folks.) Battered by hard knocks, these ragtag bands hang out at movie premieres to gawk at celebrities and sometimes they freak out and start busting balls for no apparent reason. In The Day of the Locust, they are first responsible for a bloody murder, then they riot and start setting fire to the city.

By paying homage to the Hollywood machine and its invisible workers, West was able to illuminate the film business from the bottom up. There is not much beauty to be found in what he called the “Dream Dump,” or in his chronicle of American life in the Thirties. It’s all violence all the time, with sickening scenes that still retain the power to shock. W.H. Auden would call West’s people “cripples.” They weren’t cripples to West, who lovingly described his excitable characters as “screwballs and screwboxes.” His original title for the book, The Cheated, accurately reflected their frustration.

A native New Yorker, West spent his early life managing Manhattan hotels and writing in his spare time. His first three novels earned a pathetic total of $780, hardly a living wage even during the Depression. Losing confidence in himself as a novelist, West in 1935 moved to Hollywood where he found a screenwriting job at one of the poorest studios, Republic, whose biggest stars were horses and singing cowboys. At the same time that he was learning the craft of movie writing, he was forming the ideas for his next novel.

1939 was a very good year for fiction. John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath immediately went off the grid, creating heat and noise when it shot onto the best seller list and won a Pulitzer. (Soon the book would become a movie classic starring Henry Fonda.) Unfortunately, The Day of the Locust was eclipsed by Steinbeck’s blockbuster when it was published a few weeks later. Like his previous books, it was unbought, unread, and clobbered by most literary critics, including some of West’s own friends like Edmund Wilson who took an unexpected swipe at the novel. (It did not measure up to Miss Lonelyhearts, Wilson thought.)

Writing to his friend F. Scott Fitzgerald, West sounds like a slugger who’s been knocked out: “So far the box score stands: Good reviews—fifteen percent, bad reviews—twenty five percent, brutal personal attacks, sixty percent.” Even worse, he fretted, “ Sales: practically none.”

He went on to tell Edmund Wilson that “the book is what the publisher calls a definite flop.” This was a blow because its brilliance had impressed Random House and the publisher Bennett Cerf. As a result, pre-publication prospects could not have been brighter. Turning on a dime, a vexed Cerf failed to promote the title and went on to grumble that he never wanted to see another novel about Hollywood. This proved a bit of an exaggeration because he would shortly publish Budd Schulberg’s What Makes Sammy Run? Who said the book business was soft-hearted?

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.West, devastated, was trying his damndest to sound cheerful. In truth, he felt awfully confused. “I seem to have no market whatsoever,” he said.

The Day of the Locust would be West’s last book. In December 1940 he and his wife Eileen were killed in a car crash in the middle of the lettuce fields near El Centro, California. He was 37, she was 27. That he should perish dramatically on the highway came as no surprise to his friends, because he was known to be one of the world’s worst drivers.

Despite West’s claim to be writing another novel his effects included only a few notes for a story that sounds similar to Miss Lonelyhearts. During the last year of his life he finally began achieving success as a screenwriter, a highly paid profession in the Thirties. Had he lived, I believe he would have continued to work in Hollywood as a screenwriter, director, or producer. He enjoyed the nice Southern California weather, not to mention a nice fat bank account. Would he have written more novels? Maybe. Then again, maybe not.

In the decade following his premature death, West’s fiction was pretty much ignored until it made a comeback in the 1950s. Now The Day of the Locust is a classic and its author considered one of America’s premier novelists.

Ironically, it took thirty-five years for a screen adaptation of West’s masterpiece. In 1975, John Schlesinger directed a big-budget production, whose spectacular finale showed rioters going on a rampage and setting fire to Los Angeles. Probably West would have got a kick out of seeing his screwballs and screwboxes on the screen.

Marion Meade is the author of Lonelyhearts; The Screwball World of Nathanael West and Eileen McKenney (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010). She has also written biographies of Dorothy Parker, Woody Allen, Buster Keaton, and Eleanor of Aquitaine, as well as two novels about medieval France.