Seeing Joyce

The "Bloomsday" of 2012 - 108 years after Leopold Bloom took his legendary walk around Dublin on the 16th June 1904 - was the first since the works of James Joyce entered the public domain. Frank Delaney asks whether we should perhaps now stop trying to read Joyce and instead make visits to him as to a gallery.

June 12, 2012

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

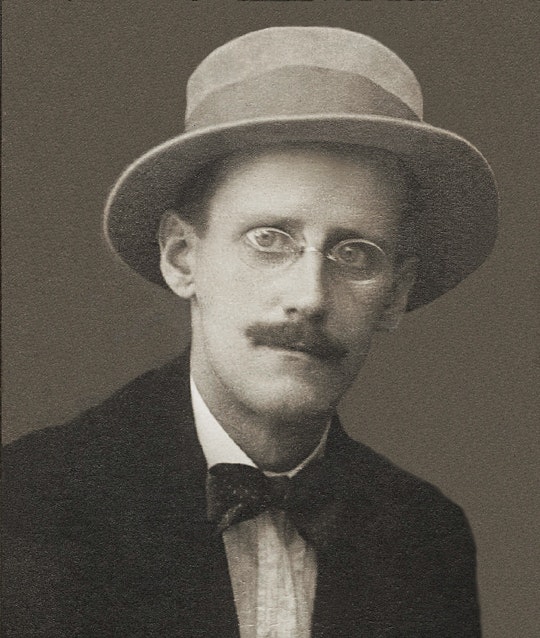

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Photograph Joyce had made in Zurich, 1915, and sent to Michael Healy, Nora’s uncle. Source: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University.

In 1931, Stanislaus Joyce wrote to his older brother, James, a letter that echoed with many voices.

I cannot read your work in progress. The vague support you get from certain French and American critics I set down to pure snobbery . . . What is the meaning of that rout of drunken words? . . . You want to show that you are a superclever superman with a superstyle.

It wasn’t the younger sibling’s first complaint, nor even the most bitter; as brother of the more famous Jim he had spoken out far more abusively at earlier, similarly “obscure” moments in the Joycean career. Nor was Stanny’s the only such complaint; in fact such allegations and dismissals would become more or less general. This time, the “work in progress” became Finnegans Wake (1939), a book that has defeated most of its would-be readers wholly and all partially, but that same frustrated opprobrium had begun with Ulysses (1922) and in due time would discolour everything that Joyce wrote.

To accept the general impeachment of James Joyce is never to know vast delight. The majority has ruled for a long time — Joyce is “difficult,” Prince of the Unintelligibles, out-Steining Gertrude and that’s that, no further argument.

If, out of sensitivity, out of respect, you find yourself reluctant to blame the artist himself, you could, if you wished, turn on the academics. Sneer at them, “Well, they certainly took Joyce at his word when he said ‘My work will keep the professors busy for three hundred years’.” Indeed. Hammer them further; didn’t they then make him exclusive, intensify his arcane reputation, isolate him from the common reader because they were hunting down all those recondite doctorates in his thickets? And, as every dog and Derrida knows, the more obscure the thesis the more summa the cum laude.

However, why yield to either frustration or cynicism, especially in the face of such great art? Since Joyce believed that his writing both synthesized and transcended other disciplines, specifically painting and music, why not look for him somewhere over there? Indeed, why not wonder whether Joyce only needs a little pathfinding, a little extra scrutiny?

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Joyce playing the guitar in Trieste, 1915. The photograph is by Ottacaro Weiss, a friend who was apparently “scandalized” by his Joyce’s guitar playing skills. The guitar is now on display at the James Joyce Museum in Martello Tower.

There’s a lot to be gained when you (sort of) set a thief to catch a thief. An artist from one discipline can refresh how we see a fellow-artist from another. Shaw on Rheingold; “Let us not forget that godhood means to Wagner infirmity and compromise, and manhood strength and integrity.” Henry James remarked upon Sir Christopher Wren’s “insincere recesses and niches” at St. Paul’s.

James Joyce attracted painters. Brancusi painted a portrait of the artist as an older man — one slender whorl and some thin tangential lines (prompting Joyce’s father to say, “Well — Jim has changed a bit since I saw him”). Matisse provided stunning illustrations for an edition of Ulysses (though by taking his inspiration from Homer he annoyed Joyce — who probably didn’t stop to think about Matisse’s language skills).

And there was one other artist, admittedly minor, who, for those seeking to understand Joyce, made the greatest of all differences. In 1918, an English painter, Frank Budgen (1882-1971), met James Joyce at a party in Zurich. Both were aged 36 and within their first conversation Joyce responded to Budgen’s natural sensitivity and felt safe with him. Rare compliment, he then showed Budgen his work in progress of the day — the first three chapters of Ulysses, four years before the book would appear in print.

If there can be a natural kinship between painters and writers, Budgen, the perfect reader, proved it. To Joyce’s “difficult” material he brought his own sense of how any artist must render life. In a memoir, James Joyce and the Making of Ulysses (1934), he described the great modernist’s prose from his own artistic vantage: “It is like an impressionist painting. The shadows are full of colour; the whole is built up out of nuances instead of being constructed in broad masses; things are seen as immersed in a luminous fluid; colour supplies the modeling and the total effect is arrived at through a countless number of small touches.”

Seen thus, Joyce’s work changes for ever. No longer do we have to read what multiple critics called “tormented prose.” The myriad disdainers, whose negatives ranged from “vulgar” and “foul” to “psychic disintegration” — they fail. As Budgen saw him, Joyce’s higher purpose gleams like dawn.

Through Budgen’s lens, not only may we now excuse Joyce the dense layers of reference, often six deep in the use or placement of a single word, we may relish them. Instead of fighting him phrase by phrase, we can trust him image by image as we see one art relating to another — literature rendered as painting. It’s like stumbling into a field of diamonds — hard, brilliant flashes of light everywhere. In short, Frank Budgen alters James Joyce’s state by making him a writer whom we see rather than merely read.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

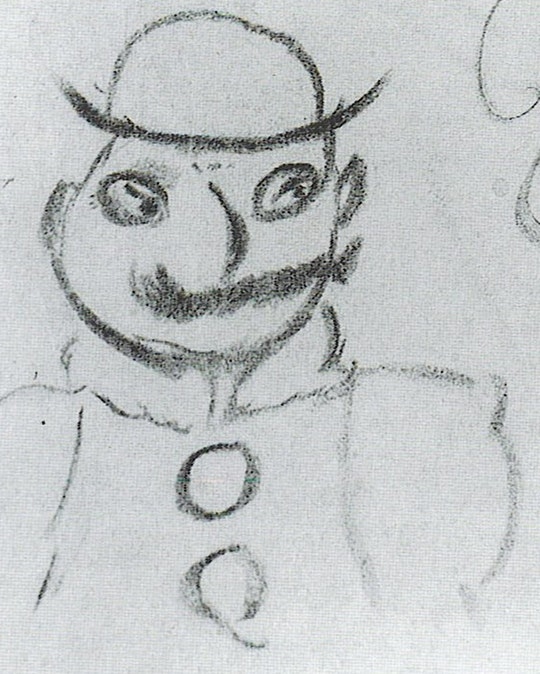

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Sketch of ‘Poldy’, Leopold Bloom, from Joyce’s notes.

That Joyce was ever thus can be discerned early. The first paragraph of his first generally published work, ‘The Sisters’, in Dubliners (1914) contains this sentence, a painting in itself: “If he was dead, I thought, I would see the reflection of candles on the darkened blind, for I knew that two candles must be set at the head of a corpse.”

Every story in the collection offers similar illustrative prose; “When she got outside the streets were shining with rain and she was glad of her old brown raincloak” (Clay). The head of a man who has fallen lies in “a dark medal of blood” (Grace). Or, straight from Renoir, “She was a slim, growing girl, pale in complexion and with hay-coloured hair.”

It’s possible to pass off the many bright phrases in Dubliners and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916) as “Show: Don’t Tell,” the creative writing school ideal. The impressionism doesn’t truly kick in until Ulysses; thereafter it dominates and does so in ways both brilliantly technical and artistically profound — and occasionally parodic. For example, in a technique vital to painting, the shift between light and shadow, Stephen Dedalus, under the sunny daylight of the most famous June morning in literature, walks along Sandymount Strand — with his eyes closed. Once the image is in place, literature then takes the meaning up, up and away — “walking into eternity,” thinks Stephen.

And yet, when the book was published in February 1922, and was at the moment the most famous book in the world, that same ‘Proteus’ chapter, with its now-notorious “ineluctable modality of the visible,” was the downfall of so many would-be readers.

Why didn’t they ask Budgen? Take the first of his three crucial remarks: “It is like an impressionist painting. The shadows are full of colour; the whole is built up out of nuances instead of being constructed in broad masses.” Use that observation to interrogate a later chapter in Ulysses, ‘The Wandering Rocks’.

It’s three o’clock in the afternoon. Lunch has been taken, Hamlet has been dissected within the Library and another landscape with figures is about to be painted. We’ve already had strong hints of this kind of canvas; Stephen steps away from a crowded bathing-place; a funeral proceeds across town; Mr. Bloom peregrinates among people and streets towards his lunch. Now, in ‘Wandering Rocks’, we are about to view the city as L.S. Lowry and his stick-figures. Or the Breughels or Averkamp, those Low Countries scenes of teeming villages. Or a Renoir afternoon.

Within the first few hundred words, we observe a grave and serious priest, who gives a blessing to a one-legged sailor, meets and greets the wife of an M.P., and chats to three little schoolboys.

Across the canvas strides a dancing teacher in “silk hat, slate frockcoat with silk facings, white kerchief tie, lavender trousers, canary gloves and pointed patent boots.”

Next we see Mrs. McGuinness, “stately, silver-haired,” with “a fine carriage . . . like Mary, Queen of Scots.” And on it goes; more schoolboys, “satchelled” this time; shopkeepers; a police constable; “two unlabouring men” lounging against the window of a pub; “a bargeman with a hat of dirty straw” — the book at this moment almost ceases to have characters; rather they become members of a painted day.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Colourised photograph of Sackville Street in Dublin, circa 1900. As I was Going Down Sackville Street was a novel by Joyce’s friend (and inspiration for Ulysses’ Buck Mulligan), Oliver St. John Gogarty — titled after an Irish Ballad which Joyce sang for Gogarty in 1904.

In 1920, for Carlo Linati, the Italian translator of his play Exiles (1918), Joyce produced The Linati Schema, a breakdown of the chapter’s nineteen segments, in which many characters recur. He listed the chapter’s concerns as “Objects, Places, Forces, Ulysses,” called the “technic” of the chapter a “shifting labyrinth between two shores,” and defined the “organ” of the piece “as “blood.” All through the ‘Wandering Rocks’ chapter the corpuscles of Dublin’s lifeblood pulse along the veins and arteries of the city.

In general, Joyce threw down many deliberate, almost sadistic challenges, not least to the “formal,” that is to say, sequential use of language. But if Ulysses is Impressionism, it can’t drag you back to its old ways. As such, it passes all Budgen’s tests, not least “the whole is built up out of nuances instead of being constructed in broad masses.” Few characters in most chapters receive great dramatic roles, and yet they all tell the story of the sixteenth of June 1904 in Dublin. Yeats wasn’t meaning to condescend when he referred to the book’s content as “the vulgarity of a single Dublin day” — he also meant vulgus, the crowd.

Twenty years before Joyce was born, the American painter, Thomas Eakins (1844-1916), wrote to a friend, “In a big picture you can see what o’clock it is, afternoon or morning, if it’s hot or cold, winter or summer, and what kind of people are there, and what they are doing, an why they are doing it.” Eakins, not an impressionist, rather a near-complete and Rembrandt-ish realist, might have been writing about all of Dubliners, a great deal of A Portrait of the Artist and many if not most of the eighteen chapters in Ulysses.

When Joyce published his two largest works, critical attention went to the monologue intérieur in Ulysses and the dream-capturing of Finnegans Wake. The former settled down as his book of the day, the latter his book of the night. All that dismay at Ulysses gave way to the desperation at “the Wake.” This was truly beyond everything.

Yet Finnegans Wake takes care of the rest of Budgen’s observations. The book behaves differently — same painter, different technique; yet again “the whole is built up out of nuances instead of being constructed in broad masses.” Budgen may have thought that he was referring to Ulysses, but the Wake was already under way when he wrote his invaluable memoir. And that novel (if such it is) is truest of all to the third part of Budgen’s opinion — “things are seen as immersed in a luminous fluid.”

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

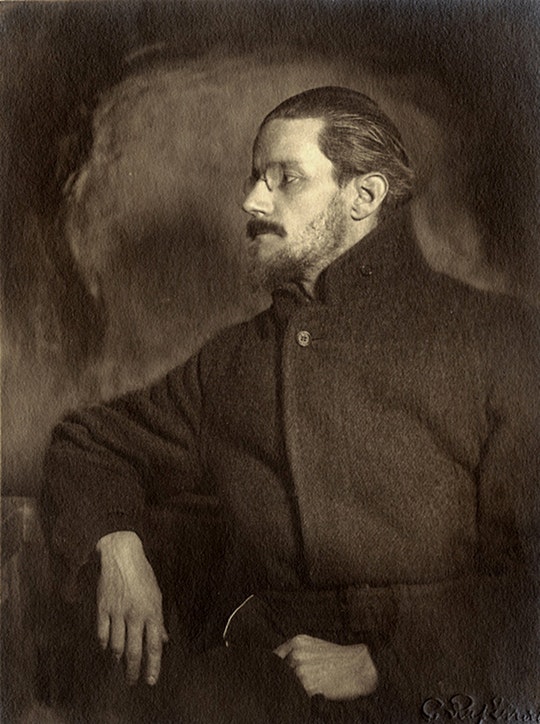

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Photograph taken of Joyce by C. Ruf. in Zurich, ca. 1918, the year he was to start work on Ulysses and met Frank Budgen.

This is where Budgen nails it. There is simply no point in trying to read Finnegans Wake by any conventional methods. Indeed, doing so would dishonor Joyce and his intention to capture the spirit’s nocturnal mechanisms, as Ulysses had the diurnal.

Best to take that phrase of Budgen’s at its face value and immerse oneself in the book’s fluid. When you read in the old way, even with conscious sound, the Wake (as Ulysses does) changes before your eyes. It becomes a dreamlike book of the dead, whose power inside Joyce’s spirit was so great that he had no choice but to use a dismembered language. Joyce was putting these sentences down on the page long before he knew of the world’s newest and widest-used language: call Finnegans Wake a binary code of literature.

But again, and at the risking of banging the drum too loud and too often, read it not as language; read it as, say, a gift of tongues or as music or as that benighted creature, the “prose poem.” And then as painting — and this time add Abstract to the Impressionists. It’s not just the sounds of the words; it’s the shapes.

Here are some examples of the text, plucked at random (Faber, 1975). The opening paragraph: “riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s, from swerve of shore to bend of bay . . .” can be a sweep of colour from the south of France. And who have we here — Jackson Pollock? “The fall (bababadalgharaghtakamminarronnkonnbronntonner- ronntuonnthunntrovarrhounawnskawntoohoohoordenenthur- nuk!) of a once wallstrait oldparr is retaled early in bed and later on life down through all christian minstrelsy.” Let’s have one more, the briefest of glimpses, a corner of a canvas and yet touchingly complete: “My great blue bedroom, the air so quiet, scarce a cloud. In peace and silence.” Taken together, this admittedly minuscule sample of three quotations is at least a sinew in Budgen’s argument.

Finally, poetry is the magnifying glass of literature’s art. Yeats called it “hammering my thoughts into unity.” Though he wrote so few, James Joyce’s verses distil his painterly claim. Read Pomes Penyeach (1927), his collection of “penny apples” (he couldn’t resist punning on pommes) and you can see his brushstrokes.

“He travels after a winter sun,/Urging the cattle along a cold red road”. Or, “A birdless heaven, seadusk, one lone star/Piercing the west”. And, hell, he’s almost pre-Raphaelite! “A waste of waters ruthlessly/Sways and uplifts its weedy mane”.

In the Carpaccio Room at the Venice Accademia, several gigantic canvases add up to nothing short of a massive literary work. Carpaccio could have called the collection, “Venetian Life and Other Stories.” Apply the same principles to Joyce and there aren’t rooms enough, nor galleries.

In the end it may all come down to the practical. Commentators have argued for Love as the one dominant element in everything Joyce wrote. There has even been a thought that if all the typos and misssteps in Ulysses could ever have been corrected, the central word in the text would be “love,” and intentionally so.

Perhaps — but Light trumps it. Page by page almost, we are never too far from the sun or the moon or the candle or the lamp or the air itself as a light source. And with good reason.

Throughout his life, Joyce suffered from poor and often painful eyesight. His eyes aged faster than he did and by his mid-forties he had endured multiple surgical procedures. In today’s terms, he’d probably qualify as legally blind. Did intensifying glaucoma impel him to his pen-dancing, pointillist-ism? Deformity, too, has its place in art.

Frank Delaney, writer and broadcaster, lives in the United States, where he deconstructs Ulysses in brief weekly podcasts on his website: www.frankdelaney.com.