The Secret History of Holywell Street Home to Victorian London’s Dirty Book Trade

Victorian sexuality is often considered synonymous with prudishness, conjuring images of covered-up piano legs and dark ankle-length skirts. Historian Matthew Green uncovers a quite different scene in the sordid story of Holywell St, 19th-century London's epicentre of erotica and smut.

June 29, 2016

Tentative warning: the essay includes some mildly explicit content, both text and image, which may not be suitable for all ages and dispositions!

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

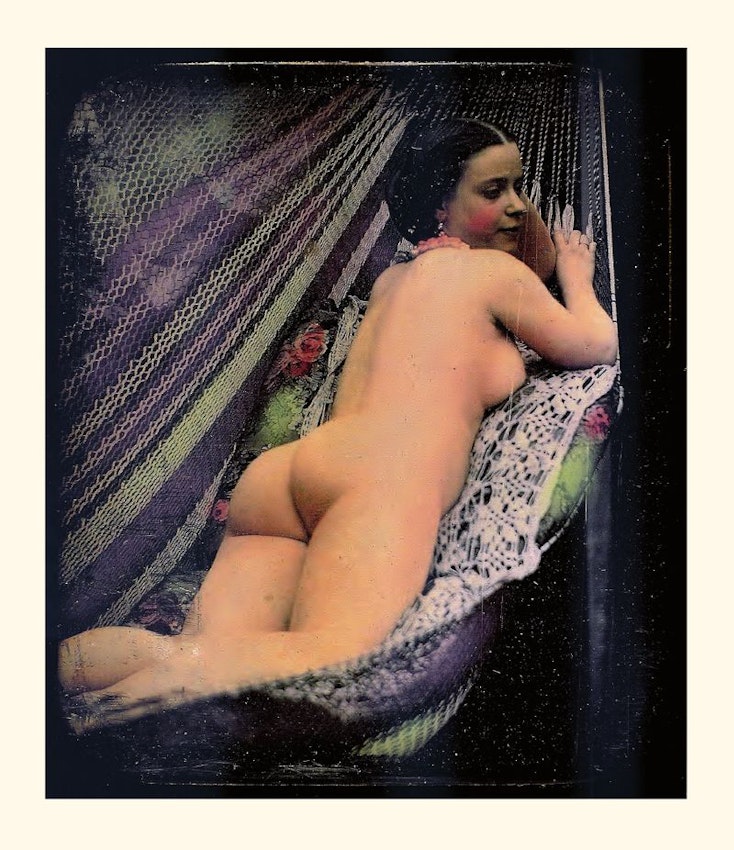

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.19th-century “French postcard” from the personal collection of the German-Austrian psychiatrist and early sexologist Richard Freiherr von Krafft-Ebing — Source.

At the eastern end of the Strand, opposite the Royal Courts of Justice, William Gladstone stands atop a plinth. Four times Queen Victoria’s Prime Minister, this eminent, emblematic Victorian is flanked by four female effigies testifying to the virtues of education, inspiration, courage, and brotherhood. Gladstone himself looks stately and solemn, as is fitting, but also mildly outraged, all clenched fists and frowns.

Well might he: he’s staring straight down what was, in his day, variously described as “a foul sink of iniquity”, “a place where dirt and darkness meet and make mortal compact” and, in the words of the Times, “the most vile street in the civilized world”. This was Holywell Street, the meridian of London’s booming pornography trade and, throughout the century, a byword for the dirty book trade long before Soho. It was the very antithesis of the noble and apparently rock-solid values embodied by Gladstone’s effigy companions and an affront to his own Christianity, which saw him scouring London’s streets late at night to rescue fallen women.

Today, the street has vanished. If you rest your back against Gladstone’s plinth and look down the Strand you have colossal Australia House in front of you; the grimy Church of St Mary Le Strand a little further down, lost amidst swirling tides of traffic; and to your right, dreary Aldwych curving towards Holborn. But from exactly the same vantage point in Gladstone’s day the scene would have been very different: two narrow, rambling streets squirrelling into the distance. One, to the right, was Wych Street; the other, tucked directly behind the Strand, was Holywell Street.

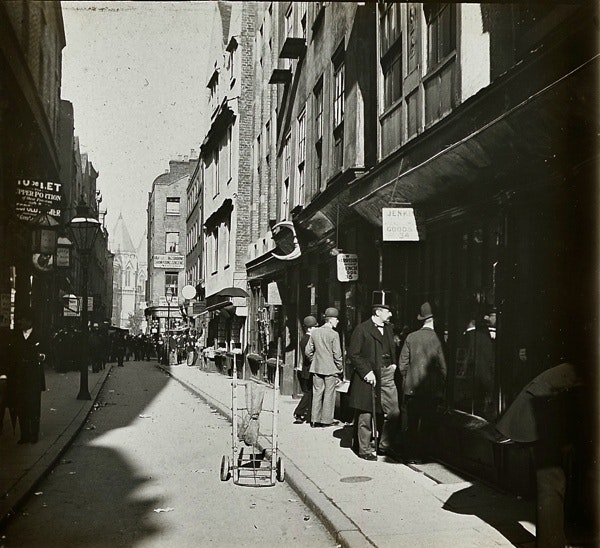

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Photograph looking west from the Church of St Clement Danes with Holywell Street to the left and Wych Street to the right — Source.

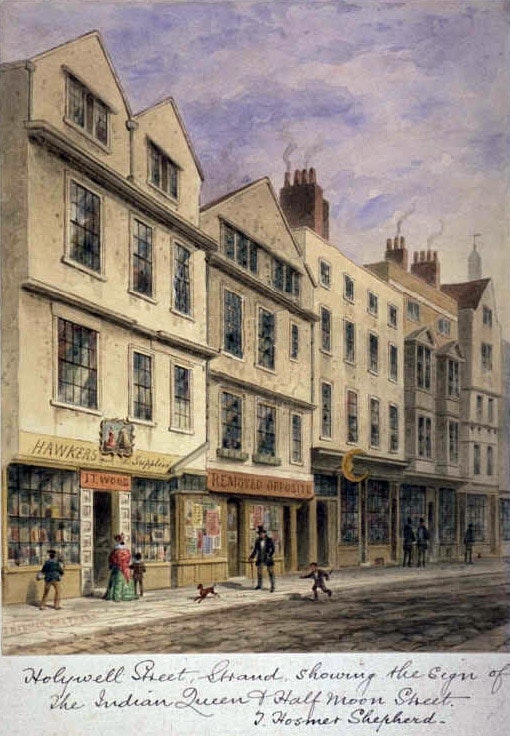

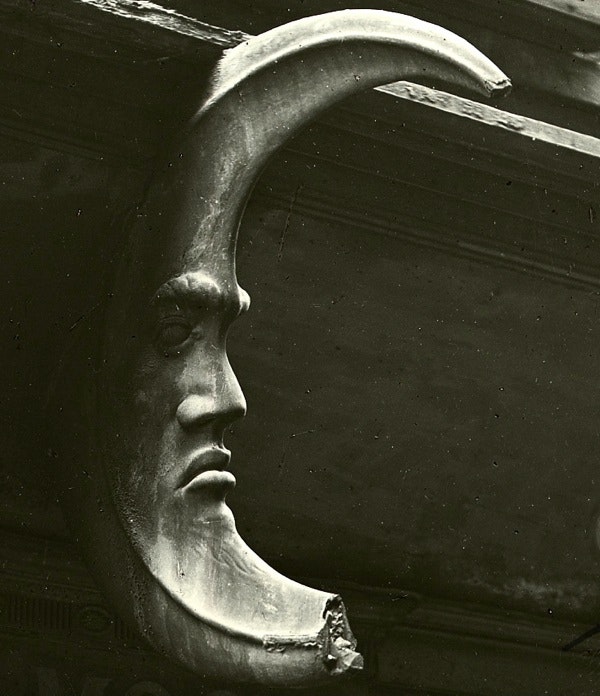

If, when it comes to the pleasures of the flesh, we are accustomed to think of the Victorians as a prudish and repressed breed, a trip down Holywell Street in the late nineteenth century would be an eye-opening experience. It was unusual in appearance. There were crooked timber-framed houses with gables lurching over the street, blocking out the light, as though caught in a time warp from medieval London. In some senses this gave it an antique, picture-postcard charm. But many of the old wooden-fronted, deep-bayed buildings were grimy and semi-dilapidated — sleazy, even. Books abounded, stuffed into sooty shop windows, spilling onto trestle tables on the pavement, and being forever unloaded from horse-drawn carts. Above one second-hand bookshop, at number 37, was a golden crescent moon with pouting lips, thick eyebrows, a fine nose, and sad, sulky eyes — reportedly the oldest shop sign in London, one that features prominently in contemporary paintings. It guarded the entrance to Half-Moon Passage, a dark alley reeking of urine, down which pedestrians could see swarms of vehicles and people on the Strand framed in a piercingly bright aperture as though caught in the lens of a camera obscura.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Painting of a picturesque-looking Holywell Street from 1864 by Thomas Shepherd. Note the bulging bay windows, overhanging storeys and the olden sign of the golden crescent moon — Source.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.A closer look at the sulky crescent moon above number 37 Holywell Street, one of the oldest shop signs in Victorian London. It can still be seen in the Museum of London — Source.

Situated on the cusp of Fleet Street, the nerve centre of the biggest publishing industry in the world, Holywell Street was originally the terrain of radical pamphleteers and printmakers. But following a government crackdown on subversive print in the 1810s, maverick publishers diverted their revolutionary impulses from radical politics into lucrative pornography, and the street became a powerhouse of the dirty book trade.

One denizen of Holywell Street was William Dugdale, one of the most prolific publishers of dirty books. He was a wily man, full of subterfuge. Some of his favourite tricks included passing off very old books as brand new simply by changing the title, or sometimes claiming new books were vintage, giving them an unjustified kudos. He also liked to rip chapters out of other people’s books and pass them off as original short works, add racy and suggestive subtitles to completely innocent novels, and write his own advertising copy, praising the brilliance of works he had himself written.

In 1857 the government passed the Obscene Publications Act, threatening pornographers with ruinous prison sentences and transforming Holywell Street into a wellspring of illicit erotica. Dugdale had to operate under at least four fake names and from several different addresses. He had managed to evade custodial sentences for some time (brazenly threatening a jury with a knife at one point) but a decade later, his luck ran out. Finally convicted, he died a lonely death in the Clerkenwell House of Corrections in 1868 having received a sentence of hard labour which, at his age, was tantamount to a death sentence.

But in spite of the draconian law, shopkeepers proved resourceful and Londoners could still find, dotted among the clothes-men’s stalls and the more respectable second-hand bookshops, dollops of pornography. “At present the sale of [illicit books and prints] is only partially suppressed”, declared the authoritative Survey of London in 1878. Of a typical day on Holywell Street, there would have been swarms of men — sometimes women too — hovering outside certain shop windows and occasionally vanishing inside to sink their teeth into the forbidden fruit of Victorian London. Suggestive title pages and obscene engravings in the window were indicative of a pornographic presence within. A mid-century Daily Telegraph article decried members of the weaker sex “furtively peeping in at these sin-crammed shop windows, timorously gloating over suggestive title-pages, guiltily bending over engravings as vile in execution as they are in subject”.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.A crowd of shoppers pore over the “sin-crammed shop windows” of Holywell Street in the late 19th century. Note the antiquated half-timbered buildings lurching over the street — Source.

And what kind of scene would have greeted customers? A dark and musty interior. The obligatory quotient of youths snout-deep in greasy books, a faint sheen of perspiration on their upper lips. A hawker arriving every so often to buy or sell. The shopkeeper eying each new customer with suspicion lest they be an undercover policeman, the bane of their existence.

Say you visited in the 1890s: staring down at you would be a range of titillating titles like The Power of Mesmerism: A Highly Erotic Narrative (1891), The Seducing Cardinal (1830), and The Lustful Turk (1864). You might also find, a little further into the shop, Captain Stroke-All’s Pocket Book! (1844), An Experimental Lecture by Colonel Spanker (1878), and The Amatory Experiences of a Surgeon (1881). Customers wouldn’t want to miss, either, The Autobiography of a Flea (1887) and Revelries! and Devilries!! (1867). The latter has a lascivious frontispiece showing two naked women with birches ready to lash a pair of bare buttocks.

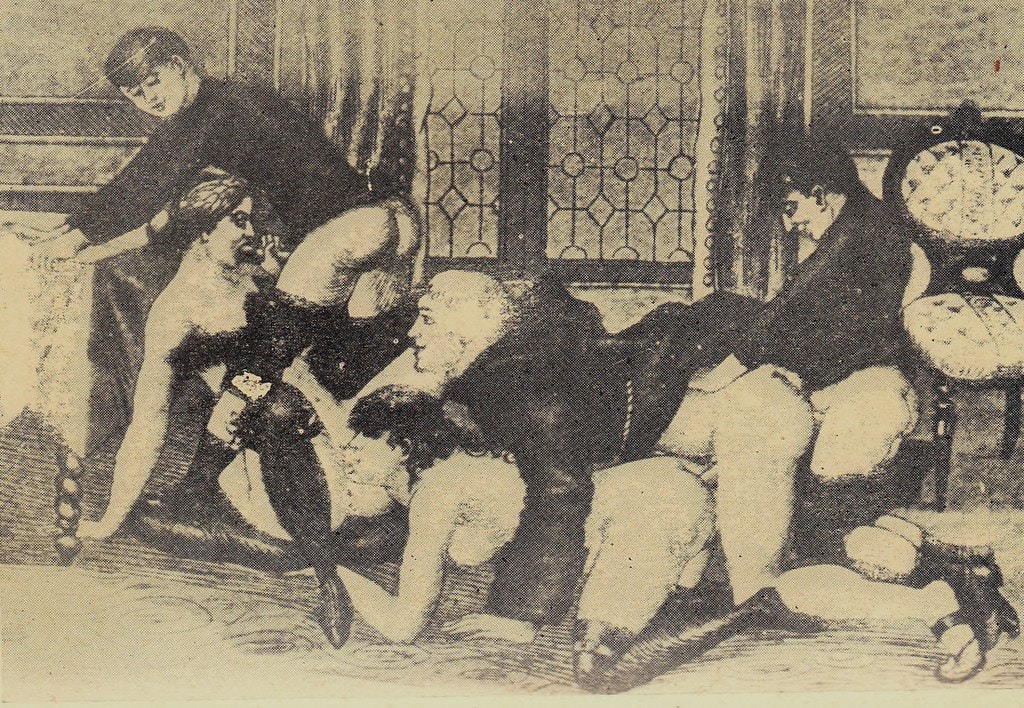

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.No orifice is wasted in this charming depiction of a drawing room gang-bang from The Autobiography of a Flea (1887) — Source.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.A friendly catch-up (with mass masturbation) from The Autobiography of a Flea — Source.

To get hold of the most illicit publications, a discreet word with the bookseller might have been necessary, and even then it may have depended on whether he was on good terms with the porn king of the day. Some, like The Story of a Dildoe! — privately printed in 1880, obscenely illustrated (you can imagine how) and limited to a print run of 150 — were very rare, passing from hand to hand much like illuminated manuscripts in medieval London. Others, like Randiana, or Excitable Tales; Being the Experiences of an Erotic Philosopher (1884), were so salacious they were kept behind the counter. In this, readers are treated to a potpourri of sexual encounters featuring orgies, ecclesiastical buggery, and lesbian sex scenes complete with gutta-percha dildoes brimming with warm oil and milk.

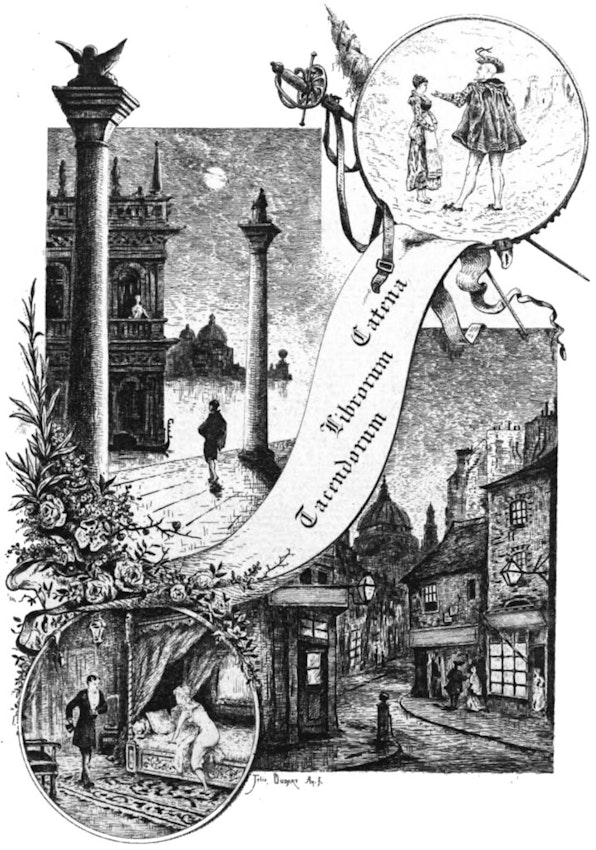

We know about these books which were readily available in Holywell Street thanks to the existence of the first pornographic bibliography in the English language, which can stake a claim to being one of the most thrilling — and longest — bibliographies ever compiled. It was published in three parts in the 1870s and 1880s by pornography connoisseur Henry Spencer Ashbee under the pseudonym Pisanus Fraxi. Ashbee was the biggest collector of pornography in nineteenth-century Europe; he would have been on first-name terms with many of the booksellers of Holywell Street. The first volume of his bibliography, published in 1877, is called the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, mocking the Catholic Church’s Index of Banned Books and fittingly so, for most of the works featured were printed privately or secretly — they were just the kind of books the police would destroy. The word bibliography doesn’t really do justice to the originality and brilliance of Ashbee’s endeavour. Part précis, part review, part critical analysis with absurdly long footnotes giving it an illusory academic quality belying the sheer filth of many of the titles, it was patently designed to stimulate as much as to inform, and is striking testimony to late Victorian London’s booming pornography industry.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Frontispiece to Catena Librorum Tacendorum (1885), the third and final volume of Henry Spencer Ashbee’s superb pornographic bibliography — Source.

The kinds of books available on Holywell Street, as listed by Ashbee, range from the fairly innocuous to the downright obscene. Ashbee describes An Experimental Lecture by Colonel Spanker, for instance, as “the most coldly cruel and unblushingly indecent of any we have ever read”. It is a sadistic account of the whipping of a young girl for the edification of the Mayfair Flagellation Society. The passages in which the victim is tied up, whipped, and penetrated tread a thin line between masochistic sex and outright assault. The self-avowed theme of the colonel’s live-action lecture was “the pleasures to be derived from crushing and humiliating the spirit of a beautiful and modest young lady”. Flagellation looms large in Victorian erotica as though a fitting punishment for protagonists so flagrantly breaching the moral codes of society.

Another striking book — not least because the writing seems so modern — is The Horn Book, or A Girl’s Guide to the Knowledge of Good and Evil (1899). Like much erotica, it takes the form of a dialogue, in this instance between a bored housewife, Maud, and her sexual tutor, Charlie, a “brilliantly healthy” and libidinous twenty-eight-year-old, and is at once a tale of sexual awakening and a vivid sex manual for practical use. It is divided up into instructive sections on the male and female sexual organs, intercourse, masturbation, sodomy, “gamahuching” (oral sex), and of course “how to fuck without danger of fecundation”. Charlie and Maud demonstrate sixty-three different sex positions including “dog-fashion flying”, “the sack of corn backwards”, “the cock horse”, and “the elastic cunt”. It contains some great pillow talk. “I should like, my angel,” says Charlie, “to crush my whole being into your sweet body; in your velvet mouth; your pretty rose-pink cunt; your delicious chocolate bum-hole, and I would squirt therein countless jets of thick, rich seed”.

In other books, it is the woman who is the sex monster, reflecting the traditional idea that women were intrinsically more lustful than men. The Delights of Love takes a “female rake” as its protagonist, an Italian widow who gives free reign to her passions and perversions after the welcome death of her impotent husband, and in The Story of a Dildoe!, “three young American ladies resolve to procure a dildo for their mutual gratification . . . then they all meet and deflower each other with this ladies’ syringe”.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Title page to an 1891 edition of The Story of a Dildoe! — Source.

If this veers into lesbian territory then The Sins of the Cities of the Plain (1881) is one of the first pornographic works to focus exclusively on male homosexual experience in which hardly anything is left to the imagination. At no point in this work — or in any of the works mentioned above — are the sexual escapades of the protagonists frowned upon; even the most depraved form of sexual activity is presented as licit, open-minded, and liberating, and the pacey, picaresque style in which many of them are written is suggestive of a certain playfulness and harmlessness much at odds with mainstream attitudes towards casual sex. Colonel Spanker, in his sordid lecture, invokes the Garden of Eden to prove that “a luscious indulgence in the arts of love” is the most natural thing in the world despite being “condemned by a hypocritical world as wicked and obscene”.

As this suggests, the Victorian establishment hailed pornographic books as evil incarnate, a corrosive threat to the very fabric of society. Ashbee describes society as being “at war” with the books; in 1856 Punch magazine wishes Holywell Street would be swallowed up by an earthquake; and one police inspector thought the “blackguard purveyors” of Holywell Street should be “taken and nailed by the ears to the nearest gatepost”. We have already noted too the deadly sentences meted out to some of the principal pornographers.

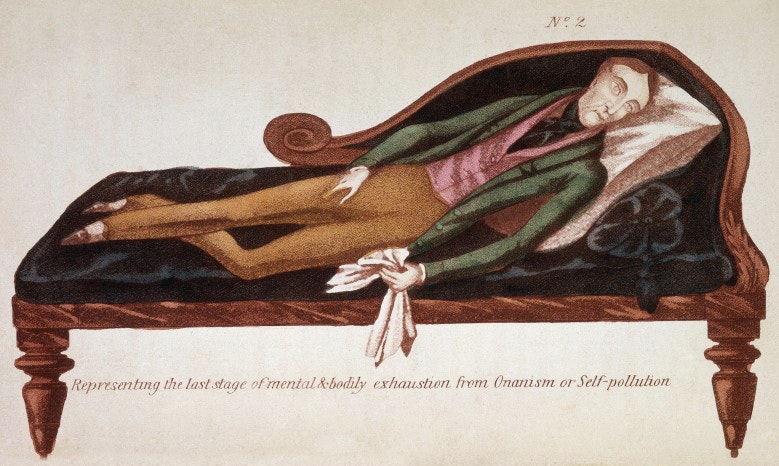

To understand why erotic novels engendered such outrage, we need to get our heads around Victorian sexuality. Male readers: imagine thinking of your body as a physiological economy with a finite amount of resources to “spend” (the most commonly used word for ejaculation in this era). Imagine being taught that every youthful sexual indulgence is an unmitigated evil which wastes your vital force and stunts your physical growth and mental development. Any kind of incontinence is dangerous, you believe, but none more so than masturbation, which will lead to jaundiced skin, eruptions of acne, a slouching gait, clammy palm, leaden eye, and the inability to look anyone in the eye. The fate of a compulsive masturbator is to become a drivelling idiot or insufferable hypochondriac. Even within the presumed safety of marriage, you will have to walk a tightrope between abstemiousness and gratification — have no sex and you’ll be ruined, but have too much and you’ll melt into a goo of despondency as the symptoms of “spermatorrhoea” (an umbrella term for diseases caused by a loss of semen) take hold, leading to heart disease and death.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.“Representing the last stage of mental and bodily exhaustion from Onanism or Self-pollution”, a coloured engraving from The Secret Companion, a Medical Work on Onanism (1845) depicting the deleterious effects of self-love stemming from a wanton waste of semen — Source: Welcome Library.

It’s even worse for women. Female readers, imagine thinking of yourself as a sexless baby-producing machine, almost entirely devoid of any erotic desire and actually incapable of it during pregnancy when your baby will suck away your vital force from within. You will surrender to your husband’s desires only occasionally. Like men, you believe that sex serves a practical purpose — the population of the earth — but beyond that it is profoundly dangerous. Continence is the key. Your sex life is likely to be a sore and bitter trial.

These ideas, so farcical and objectionable to twenty-first-century eyes, are lifted — sometimes word for word — from Dr William Acton’s Functions and Disorders of the Reproductive Organs (1857), no radical polemic but mainstream medical opinion. Anyone deviating one iota from his worthy advice (memorably described by historian Steven Marcus in The Other Victorians [1966] as “part fantasy, part nightmare, part hallucination”) is either indifferent to their health or just plain low. It is only after we get our head around Dr Acton’s alien sexual precepts that we can begin to understand the hysterical tone that united police, press, and politicians in lambasting pornography. For Victorian pornography was not just a foil to Dr Acton’s belief system but its antithesis, presenting as it does a world of sexual riches where women are game for anything and men are “limitlessly endowed with that universal fluid currency which can be spent without loss”, as Marcus puts it. Even Ashbee calls pornographic works “poisons” in the preface to his bibliography, warning that they must be distinctly labelled and “confined to those who understand their potency”. They are also, of course, an incentive to dreaded masturbation. That is why men like William Dugdale had to be destroyed in hard-labour camps.

The perversions of Holywell Street pornography sometimes spilled over into real life. “This literature amused me much, as did the pictures of fantastic combinations of male and female in lascivious play and coition”, writes “Walter”, a pornography connoisseur and pseudonymic author of My Secret Life. “I began to see that such things are harmless, though the world may say they are naughty, and saw through the absurdity of conventional views and prejudices as to the ways a cock and cunt may be pleasurably employed”. My Secret Life was an Odyssean sexual memoir privately printed from 1888 and running to four thousand pages across eleven volumes. With its vivid descriptions of deviant sexual behaviour, it reveals that not everyone adhered to middle-class sexual ideals, to put it mildly. The memoir is so frank that a British printer was sentenced to two years’ imprisonment for supplying it — in 1969! It still has the power to shock today with sentences like “while I fucked her, I hated her — she was my spunk-emptier” and “her cunt constricted . . . and sucked round my prick from tip to root moistening both itself and occupant, and my sperm shot out and filled it”.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.A cheerful illustration by French painter and lithographer Achille Devéria, ca. 1840 — Source.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Reluctant lovers in a pornographic postcard from the 1880s — Source.

Over the course of a million words, Dr Acton’s sexual worldview is capsized. In the text, men can philander away to their hearts’ content — they will suffer no adverse effects unless they catch a sexually transmitted disease, which is always a risk for men like Walter. Nor are women passive and sexually submissive in the least; all you need to do, in Walter’s world, is fill them up with wine and meat, “let the grub work”, and they’re anyone’s. And they enjoy it, women, as the many sex scenes ram home. Nor are men, contrary to Dr Acton, in their uninhibited state always sex machines. My Secret Life addresses the taboo of impotency. “My God! It was not standing, not a bit of swell or stiffness was in it”, writes a horrified Walter at one point, finding his genitalia reduced to “a sucked gooseberry, a mere bit of dwindling, flexible, skinny gristle”. Overall, Walter’s memoir is a violent reaction against the repressed nature of Victorian sexuality and a striking manifestation of the sort of sexual freedom glimpsed in pornography. The problem, it seems to be saying, lies with society not pornography.

In the latter part of the century, if customers wanted to get hold of pornographic prints or even stereoscopic slides (giving the illusion of depth to indecent images), they usually had to have a discreet word with the bookseller. Even then, they were likely to have been treated with suspicion. In 1880, a police inspector went undercover in search of a family-run mail-order enterprise that was corrupting Eton pupils by sending them indecent images unsolicited in envelopes marked “art studies”, in the hope that they would order more. The trail led straight to a Holywell Street bookshop. The officer found that risqué photographs could be purchased easily enough but to get his hands on some “choice specimens”, as he puts it in his Stories from Scotland Yard (1890), the police officer had first to earn the keeper’s trust before being led upstairs into “a dirty little place, which was part bed-room, part workshop . . . as filthy a hole as I have ever been into”. Here, he purchased some expensive hardcore pornography (for two guineas) — and left a shilling for the “little wretched piece of forlorn humanity” that was the shopkeeper’s baby. The pornographer’s suspicious wife followed him to the train station. The next day, the shop was raided, five thousand indecent photographs seized, and the man arrested. He was given two years’ imprisonment and the inspector rejoices in ending his “revolting trade”.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Erotic illustration by Achille Devéria, ca. 1840 — Source.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Hand-coloured erotic photograph, ca. 1855 — Source.

If the sight of the pornographic prints and slides aroused customers, they could walk to the end of Holywell Street and double back into Wych Street. In appearance, it was similar to Holywell Street: grimy, narrow and with gables toppling over the street, but here many of the buildings were brothels — some flagellation brothels. Holywell Street was not known for its houses of ill repute but many of its chemists stocked sex toys.

In spite of repeated police and government crackdowns, the pornographers of Holywell Street proved resilient. Every time one head honcho of the porn trade was arrested, another simply popped up in his place; the street’s shopkeepers were ever alive to the enormous commercial potential of smut. It began to look like the only way to suppress Holywell Street for good was to wipe it off the map. There had in fact been, throughout the course of the nineteenth century, a series of proposals to demolish Holywell Street and Wych Street, ostensibly to make the Strand wider and grander — it could become horribly congested between the churches of St Clement Danes and St Mary le Strand. But the prospect of exterminating the pornography trade gave the proposals added piquancy.

And, right at the end of the nineteenth century, that is exactly what happened. By 1901, both Holywell and Wych Street would be gone, flattened to make way for soulless Aldwych, which was completed just after the First World War. London’s pornography trade didn’t vanish with them of course; its centre of gravity simply shifted to the other end of the Strand, to Charing Cross Road, which became the new nucleus of erotic books, and, after that, to Soho where sex bookshops can still be found to this day.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Holywell Street, flattened, 1902 — Source.

Matthew Green is a historian and broadcaster with a doctorate from the University of Oxford. He writes for national newspapers, has appeared in many television documentaries, and is the author of London: A Travel Guide Through Time and Shadowlands: A Journey Through Lost Britain. He lives in London.