A Family Tree: Hippolyte Hodeau’s Trench Art (ca. 1917)

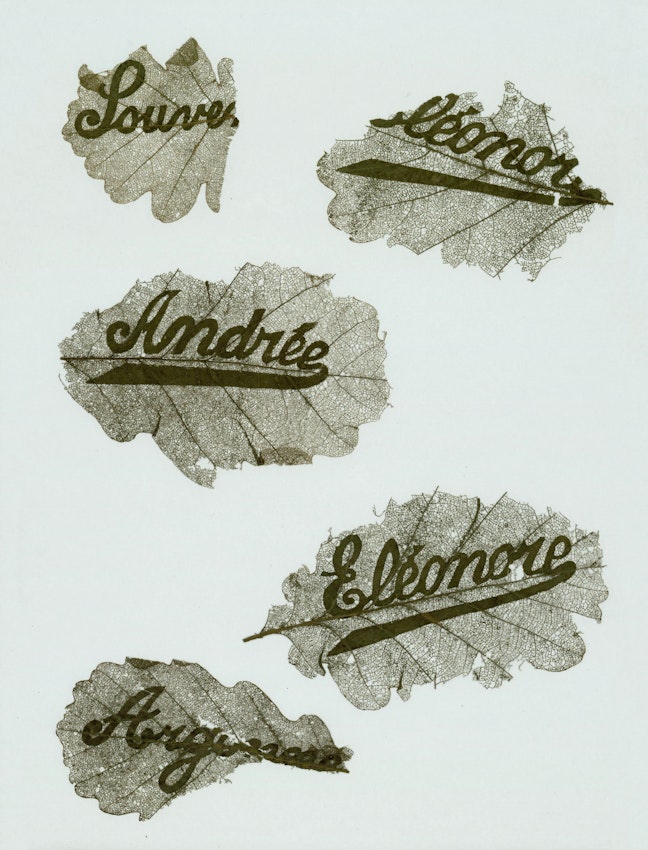

Thierry Dornberger’s family keepsakes include a memento exceptionally delicate. His great-grandfather, Hippolyte Hodeau, was a World War I private who served in Argonne. As Dornberger relates, Hodeau “made the trenches and was gassed. Following the dull sound of a shell falling . . . he was wounded in the ear.” Like many soldiers, Hodeau spent hours huddled in these muddy channels. In order to kill time, perhaps, or lift his spirits, he gathered leaves from an oak tree — elongated, striated, forest green — and used a form of relief carving to inscribe the names of his daughters, Andrée and Eléonore, as well as the word “souvenir” and what looks like “Argonne”.

“Trench art”, as it’s called, wasn’t necessarily fashioned in dugouts and wasn’t usually so fragile. Collectors seek out letter openers made of shrapnel; crucifixes made of bullets; and artillery shells fashioned into everything from bracelets to clocks to candelabras. Wooden walking sticks were festooned with intricate carved heads, and tiny valentine pillows sewn and beaded for sweethearts back home. Hodeau’s engraved leaves are part of this resourceful genre, but there is another artistic tradition to which they also belong — that of arborglyphs, or tree carving. Humans have long regarded trees as witnesses. Basque sheepherders in the American West wrote poetry on birch, Confederate Civil War soldiers graffitied their names in trunks, and various Aboriginal Australian tribes honored the dead on bark. Whereas these gestures leave a bit of the human in the landscape, Hodeau’s engravings take a bit of the landscape with the human. “I was here” says one; “I was there” says the other.

As unique as his objects may seem, Hodeau was not alone in carving leaves. The art form flourished during World War I as a way to enhance letters home with a unique lightweight enclosure. Soldiers used a needle or knife to whittle between the oak and chestnut veins, leaving only words or, sometimes, an image. Due to the partial opacity of perforated leaves, the carvings are especially enchanting when lit from behind; sometimes they’re called “feuilles de poilus”, or “tree leaf lace”.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

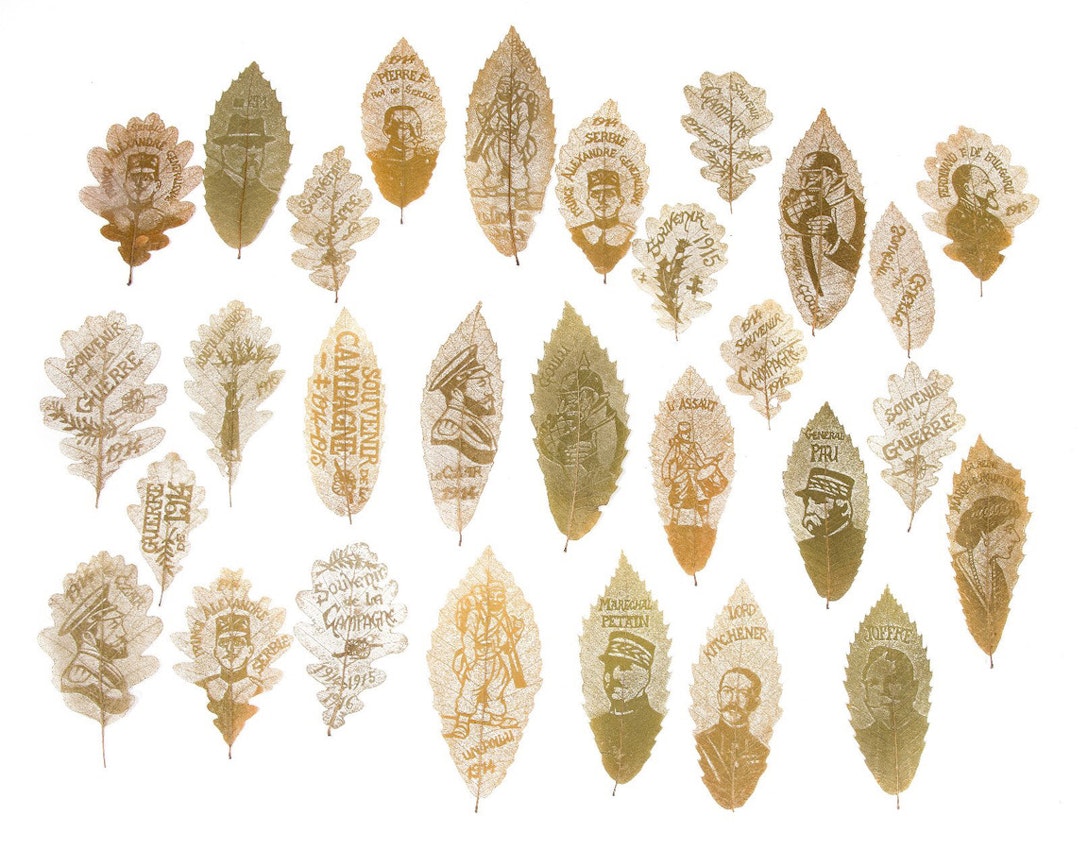

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.“Feuilles de Poilus” exhibited by the In Flanders Fields Museum in 2022 — Source (not public domain).

Little has been written about this kind of memorialization, but French military history forums brim with amateur investigators and collectors. The user “GillesR”, for instance, reports tracing a leaf that reads “Souvenir Alsace” to an infantryman named Bringuier, who was left for dead on the battlefield in 1914, captured by the Germans, and subsequently released as unfit for combat after the amputation of his left arm. Andre Dupuis of the 52nd Territorial Infantry Regiment emblazoned “CapNap” in 1915, whereas Alfred Laperrière was fond of writing longer, more complicated phrases — “Souvenir de Serbie” (Serbian souvenir); “Je pense à toi” (Thinking of you); “Ton mari aimant” (Your loving husband).

Words predominate, though there are startling exceptions. The Jardin Botanique de Nancy claims to have unearthed a silhouette of a soldier in profile, perhaps a self-portrait. Bernard Dauphin’s website gathers an assortment of leaves reading “Souvenir”, “Helene”, and “Yvonna” (the last enclosed in a heart), and tells of meeting a Frenchman who was deported to Germany during World War II under the service du travail obligatoire and who survived by traded carved leaves for sausage. Other specimens have no author, and no story. It seems that these type of leaves have only recently been gathered for exhibition. A 2022 show at the Halle Saint-Piere in Paris apparently included a “mémoire végétale de la Grande Guerre” (botanical memorial of World War I), while the In Flanders Fields Museum in Ypres, Belgium, exhibited a remarkable collection of leaf portraiture in that same year.

This eco-trench art might have quietly composted were it not for Europeana’s 1914–1918 project, which drew attention to the phenom by soliciting information from the public and digitizing thousands of fragile artifacts.

Mar 26, 2024