The Art of Swimming (1587)

During a 1934 lecture to the Sociéte de Psychologie in Paris, Marcel Mauss, “the father of French ethnology”, admitted frustration. What interested him most about culture was often filed away under “miscellaneous”, for his subject matter did not readily reveal its significance: “I was well aware . . . that the Polynesians do not swim as we do, that my generation did not swim as the present generation does. But what social phenomena did these represent?” Everard Digby's 1587 De Arte Natandi (The Art of Swimming), considered the first English treatise on the practice, makes a perfect case study for Mauss’ question, revealing how seemingly innate human practices can be cultural techniques, which ebb and flow over time, like the beautiful freshwater bodies within which its woodcut figures wade.

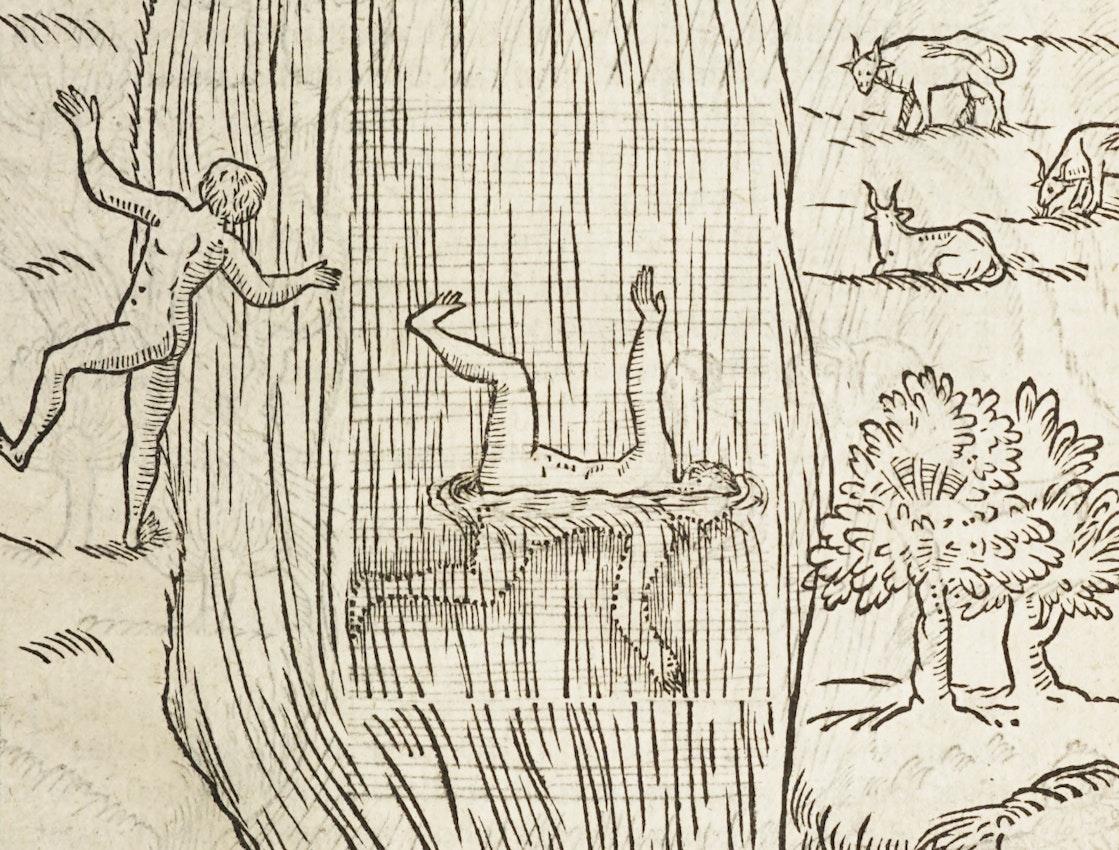

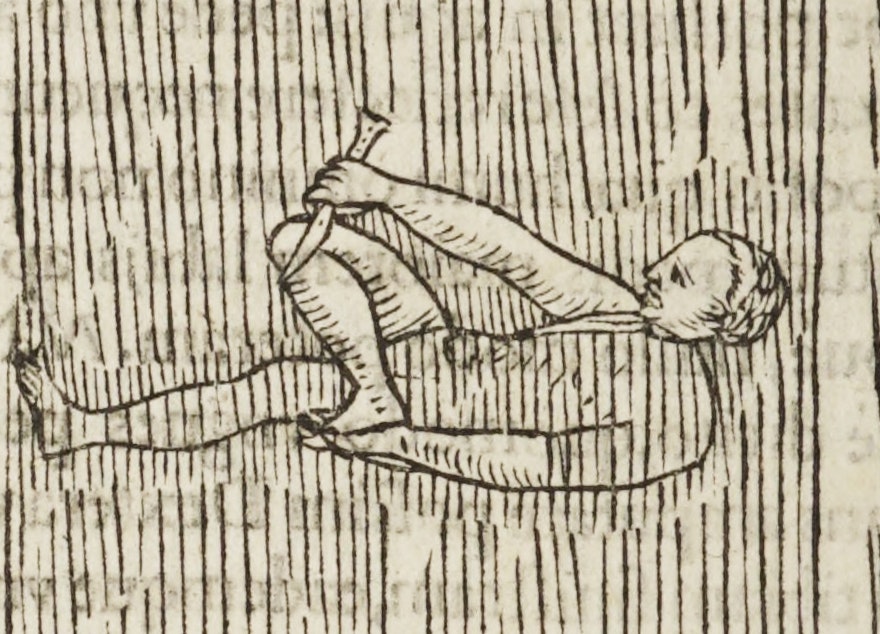

Divided into two parts, the first is largely theoretical, written in a baroque, allusion-heavy Latin that, in John M. McManamon’s words, has “bedeviled readers” ever since. (Digby’s work would be translated into English by Christopher Middleton eight years later.) The second part is concerned with practical demonstration borne out in a series of forty-two beautiful woodcuts, all composed from five landscape blocks into which swimmers in various positions have been placed. The work was hugely influential. In Ocean (2020), Steve Mentz calls Digby’s work the “central historical text marking the upsurge of interest in swimming in early modern England”. Its fame came not just from providing a practical guide to staying afloat and different strokes, but also from its attention to issues of safety.

The techniques range from the common backstroke and doggy paddle — “To swimme on the back”; “To swim like a dog” — to fanciful practices like aquatic toe-nail clipping and gestures now associated with synchronized swimming: “To pare his toes in the water”; “to stroake his legge as if he were pulling on a boote”. Some instructions are comically terse. How does one swim like a dolphin? You simply breathe: “This is nothing els, but in diuing to lift his head aboue the water, & when he hath breathed, presently diue down againe, as afore.” Much more detailed are the descriptions of best practices for safe swimming. As the Wellcome Library Blog discusses: “The work is alive to the dangers of swimming outdoors: Digby makes careful note of the safest methods of entering rivers, warning against jumping in feet first (particularly if the water has a muddy bottom to which your feet would stick) and advocating a slow and patient entry.”

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.“To pare his toes in the water”

Born in 1550, Digby was an academic theologian at Cambridge University, where he may have taught Thomas Nashe how to swim. As Mentz records, “the images in his book resemble local aquatic hunts along the River Cam”. In 1587, the same year as his swimming treatise was published, Digby was expelled from St John's partly due to his habit of blowing a horn and shouting around the College grounds.

As a historical document, De Arte Natandi’s avoidance of the crawl-like strokes provides an early example of the longstanding European resistance to this technique and its variations — that is, swimming with one’s head submerged in water. In 2022’s Shifting Currents: A World History of Swimming, Karen Eva Carr tracks how colonial Europeans associated the overhand crawl with “uncivilized” indigenous American and African practices well into the nineteenth century. As late as 1906, American coaches were claiming that, while the crawl was “the fastest of all known swimming strokes”, it was “almost useless, as it is very exhausting”. And yet, unlike later philosophers of sport who would try to defend human swimming as a civilized art in contrast to the wild movements of fish and waterfowl, Digby knew the practice to be perfectly natural:

The Fishes in the Sea, whose continuall life is spent in the water, in them dooth no man denie swimming to be the onely gift which Nature hath bestowed vpon them, and shall wee thinke it then artificiall in a man, which in it dooth by many degrees excell them, as dyuing downe to the bottoms of the deepest waters, and fetching from thence whatsoeuer is there sunck downe, transporting things to and fro at his pleasure, sitting, tumbling, leaping, walking, and at his ease perfourmeth many fine feates in the water, which far exceeds the naturall gifts bestowed on Fishes? nay so fit is the constitution of mans body . . .

Below you can browse selections of the woodcuts, courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.

Aug 28, 2014