The Lancashire Witches 1612-2012

Not long after ten Lancashire residents were found guilty of witchcraft and hanged in August 1612, the official proceedings of the trial were published by the clerk of the court Thomas Potts in his The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster. Four hundred years on, Robert Poole reflects on England's biggest witch trial and how it still has relevance today.

August 22, 2012

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Woodcut of witches flying, from Mathers’ Wonders of the Invisible World (1689) and used in an 18th-century pamphlet about the Lancashire witches.

Four hundred years ago, in 1612, the north-west of England was the scene of England’s biggest peacetime witch trial: the trial of the Lancashire witches. Twenty people, mostly from the Pendle area of Lancashire, were imprisoned in the castle as witches. Ten were hanged, one died in gaol, one was sentenced to stand in the pillory, and eight were acquitted. The 2012 anniversary sees a small flood of commemorative events, including works of fiction by Blake Morrison, Carol Ann Duffy and Jeanette Winterson. How did this witch trial come about, and what accounts for its enduring fame?

We know so much about the Lancashire Witches because the trial was recorded in unique detail by the clerk of the court, Thomas Potts, who published his account soon afterwards as The Wonderful Discovery of Witches in the County of Lancaster. I have recently published a modern-English edition of this book, together with an essay piecing together what we know of the events of 1612. It has been a fascinating exercise, revealing how Potts carefully edited the evidence, and also how the case against the ‘witches’ was constructed and manipulated to bring about a spectacular show trial. It all began in mid-March when a pedlar from Halifax named John Law had a frightening encounter with a poor young woman, Alizon Device, in a field near Colne. He refused her request for pins and there was a brief argument during which he was seized by a fit that left him with ‘his head . . . drawn awry, his eyes and face deformed, his speech not well to be understood; his thighs and legs stark lame.’ We can now recognize this as a stroke, perhaps triggered by the stressful encounter. Alizon Device was sent for and surprised all by confessing to the bewitching of John Law and then begged for forgiveness.

When Alizon Device was unable to cure the pedlar the local magistrate, Roger Nowell was called in. Characterised by Thomas Potts as ‘God’s justice’ he was alert to instances of witchcraft, which were regarded by the Lancashire’s puritan-inclined authorities as part of the cultural rubble of ‘popery’ — Roman Catholicism — long overdue to be swept away at the end of the county’s very slow protestant reformation. ‘With weeping tears’ Alizon explained that she had been led astray by her grandmother, ‘old Demdike’, well-known in the district for her knowledge of old Catholic prayers, charms, cures, magic, and curses. Nowell quickly interviewed Alizon’s grandmother and mother, as well as Demdike’s supposed rival, ‘old Chattox’ and her daughter Anne. Their panicky attempts to explain themselves and shift the blame to others eventually only ended up incriminating them, and the four were sent to Lancaster gaol in early April to await trial at the summer assizes. The initial picture revealed was of a couple of poor, marginal local families in the forest of Pendle with a longstanding reputation for magical powers, which they had occasionally used at the request of their wealthier neighbours. There had been disputes but none of these were part of ordinary village life. Not until 1612 did any of this come to the attention of the authorities.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Illustration from James Crossley’s introduction to Pott’s Discovery of witches in the County of Lancaster (1845) reprinted from the original edition of 1613.

The net was widened still further at the end of April when Alizon’s younger brother James and younger sister Jennet, only nine years old, came up between them with a story about a ‘great meeting of witches’ at their grandmother’s house, known as Malkin Tower. This meeting was presumably to discuss the plight of those arrested and the threat of further arrests, but according to the evidence extracted form the children by the magistrates, a plot was hatched to blow up Lancaster castle with gunpowder, kill the gaoler and rescue the imprisoned witches. It was, in short, a conspiracy against royal authority to rival the gunpowder plot of 1605 — something to be expected in a county known for its particularly strong underground Roman Catholic presence.

Those present at the meeting were mostly family members and neighbours, but they also included Alice Nutter, described by Potts as ‘a rich woman [who] had a great estate, and children of good hope: in the common opinion of the world, of good temper, free from envy or malice.’ Her part in the affair remains mysterious, but she seems to have had Catholic family connections, and may have been one herself, providing an added motive for her to be prosecuted. She was, along with a number of others named by the children, rounded up, and by the time of the trial in August the Pendle accused had been joined in the dungeons of Lancaster Castle by other alleged witches from elsewhere in the county.

All nineteen were tried in the space of two days, amid dramatic courtroom scenes. Ten of them were hanged the next day on Lancaster Moor, high above the town and overlooking Morecambe Bay. It was probably the first time any of them had seen the sea.

Alice Nutter and several other defendants defied convention by refusing to offer any confession on the gallows. To many of those present at the hanging this would have seemed like proof of innocence, and it may have been such rumblings about the trial that prompted the trial judges to ask the clerk of the court, Thomas Potts, to take the unusual step of publishing an account of it. In truth Potts had already had a large hand in organising the trial itself and may well have suggested the publication in the first place. He certainly used it to curry favour with King James I, whose book Demonology he cited several times, proclaiming how the authorities had followed the King’s advice on uncovering cases of witchcraft in the Lancashire trial. The Lancashire trial was then cited from the 1620s onwards as the legal precedent for using child and ‘supergrass’ evidence in witchcraft cases. Indirectly, the trial of the Lancashire witches may have influenced the notorious ‘witchfinder-general’ trials of the 1640s and even the Salem witch trials of the 1690s in New England.

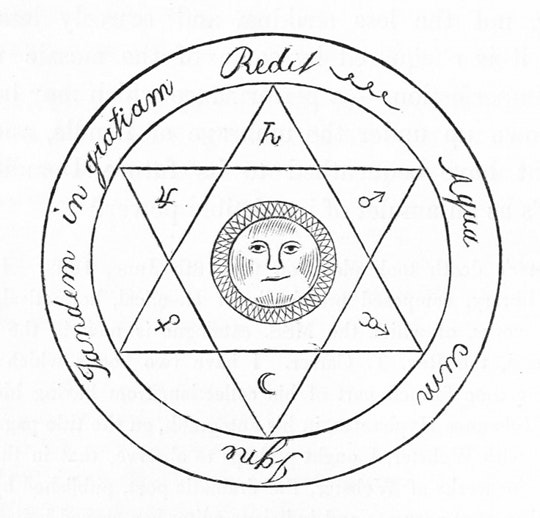

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Thomas Potts as he was imagined in Harrison Ainsworth’s The Lancashire witches, a romance of Pendle Forest (1850), illustrated by Sir John Gilbert.

The modern fame of the Lancashire witches is down to the publication in 1849 of an imaginative novel by Harrison Ainsworth, a friend of Charles Dickens with local connections and one of the bestselling Victorian novelists. His novel The Lancashire Witches has never been out of print, and it was successful in part because to drew on an edition of Potts’ original book published in 1848 by Ainsworth’s friend James Crossley, the Manchester antiquarian. Ainsworth has in turn inspired many other publications and theories. The trial began to receive serious academic attention in the 1990s, pulled together in a book of essays which I edited for Manchester University Press, The Lancashire Witches: Histories and Stories. In 2012 an international conference at Lancaster University, Capturing Witches, will bring together the latest work, both factual and fictional. No fewer than five new novels have appeared, most notably Jeanette Winterson’s At Daylight Gate, as well as a book of verses by Blake Morrison, A Discovery of Witches, and a BBC documentary, The Pendle Witch Child.

The remarkable range of new work testifies to the richness of historical themes thrown up by the trial, but I would like to single out one in particular: children and witchcraft. Much of the key evidence in the trial of 1612 was given by two children, James and Jennet Device, aged about nine and twelve. Caught up in a terrifying web of charges and arrests they panicked, and their stories, designed to clear themselves, ended up in the deaths of most of their own family members, and indeed of James himself. In some parts of the world, children continue to be accused of witchcraft and to suffer horrific maltreatment as a result. A case of a Nigerian child in London, tortured and murdered by their own family for being a witch, recently hit the national headlines. Lancaster, home of the 1612 trials, is also home of Stepping Stones Nigeria, a campaigning charity dedicated to protecting children from accusations of witchcraft and other abuse. It has been adopted as the charity of the Lancashire Witches 400 programme. There could be no better way of marking the anniversary of the Lancashire witches trials than to visit their website and learn more about how witchcraft remains a live issue, four hundred years on.

Robert Poole is the author of The Wonderful Discovery of Witches in the County of Lancaster (Carnegie, £7.95), and the editor of The Lancashire witches: Histories and Stories (Manchester UP, £14.99).