The Myth of Blubber Town, an Arctic Metropolis

Though the 17th-century whaling station of Smeerenburg was in reality, at its height, just a few dwellings and structures for processing blubber, over the decades and centuries a more extravagant picture took hold — that there once had stood, defying its far-flung Arctic location, a bustling urban centre complete with bakeries, churches, gambling dens, and brothels. Matthew H. Birkhold explores the legend.

July 10, 2019

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.The Whale-oil Refinery near the Village of Smerenburg (detail), showing various installations with smoking chimneys and large groups of workmen — Source.

Perched on a desolate island in the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard — 1,500 kilometers north of the Arctic Circle — sits the settlement of Smeerenburg. Founded by Dutch whalers in 1619, Smeerenburg — literally “Blubber Town” — was once the busiest polar site for rendering oil from blubber. As new hunting grounds and technologies rendered land-based processing obsolete, the outpost became unnecessary. Faraway Smeerenburg was abandoned by 1663. Despite its brief existence, myths of a bustling Blubber Town lived on. Sailors recounted streets lined with churches, shops, and bakeries. Other tales described the clubs and brothels forlorn whalers could visit. Respected scientists and historians, including William Scoresby and Fridtjof Nansen, repeated the stories, claiming tens of thousands of people dwelled on the icy island. In reality, no more than fifteen ships carrying four hundred men visited the site.

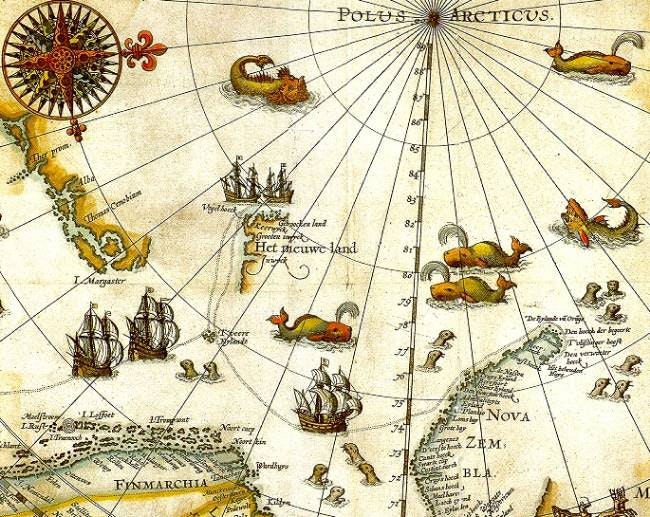

Smeerenburg began with a happy accident. Searching for a Northeast Passage in 1596, famed navigator Willem Barentsz (1550–1597) stumbled upon the Svalbard islands. Here, along the rocky coasts, he found countless bowhead whales and saw an opportunity. The Dutchman planted a flag and claimed the lucrative waters for the United Provinces.

For the next century, the Dutch ruled the whale trade, supplying almost all of Europe with oil for lamps and whale bones for corsets and hoop-skirts. The peerless Dutch navy safeguarded sailing routes against English, German, and French interlopers as Dutch whalers asserted exclusive rights to the best hunting grounds in the Arctic. The resulting near monopoly allowed Dutch companies to keep prices artificially high and further gild their coffers. The legacy of this Golden Age dominance is recorded in our language: in addition to maritime words like “maelstrom”, “skipper”, and “cruise”, the terms “iceberg” and “walrus” also stem from Dutch exploits in the Arctic.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Detail from Dutch explorer Willem Barentsz’s 1598/9 map of the Arctic in which Spitsbergen, here mapped for the first time, is indicated as “Het Nieuwe Land” (Dutch for “the New Land”), center-left — Source.

In 1614 an alliance of Dutch cities created the Noordsche Compagnie as a whaling cartel, which sent ships north each June. Following a three-week journey, the ships arrived to what they called Spitsbergen and remained until September or October, when the growing ice threatened to trap them. At the time, whales were hunted near the coasts and in fjords.

Harvesting the “gold of the seas” was arduous. Bowhead whales were the favored target of Dutch speculators because they are slow swimmers and possess vast quantities of blubber. They can grow up to 60 feet and weigh more than 100 tons. The whip of a tail could spell death. Once a whale was spotted, men hurried to small boats and rowed toward the beast. A successful throw would lodge a harpoon behind the whale’s eye, causing it to dangerously thrash and flee, dragging the craft through freezing waters. Once they exhausted the whale, the crew could repeatedly pierce it. A final lance to the organs would kill the animal, which would roll over, ready to tow back to the ship floating belly up.

Back on shore, men stood atop the giant carcass and flensed the blubber from the muscle, ending up hip-deep in blubber and blood. The process could take hours or days, depending on the size of the whale, the skill of the crew, and the weather. In the seventeenth century, the extracted blubber was cut into manageable pieces and boiled in enormous iron ovens to render oil. After cooling in wooden casks, the oil was funneled into barrels and loaded onto ships to be sold on the European market. Besides alleviating the potential fetor of rotting blubber aboard, producing oil on shore saved space in the hold and thus increased profits.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.The Whale-oil Refinery near the Village of Smerenburg (detail), showing the flensing of a whale — Source.

During their first expedition in the Arctic, ships from the Noordsche Compagnie set up camp on a narrow promontory off a small island near the northwest coast of Spitsbergen. They named it Amsterdam Island. The whalers returned to the same site each summer with canvas tents and makeshift ovens. In 1619, they arrived with timber, brick, and peat from home to create a permanent whaling station. The settlement came to be called Smeerenburg — a fitting name given the heaps of blubber (smeeren) carved up at the site. As more ships arrived each year, additional oil cookeries were built as well as storehouses and dwellings. The buildings were named for the cities that owned them: Delft, Enkhuizen, Hoorn, Middelburg, and Veere among others.

Word of a booming Blubber Town spread among whalers in the Arctic. There was no agreement on how large it had grown and when it was deserted. Most believed it was a bustling place. Written accounts corroborated the whalers’ yarns for a broader public. Jacob Segersz van der Brugge, for instance, published his journal shortly after returning home from whaling in 1634. He describes the lodgings — the Middelburg “tent” he occupied measured 21 by 16 feet — and catalogues his diet, including fresh meat from reindeer, foxes, and birds. Van der Brugge even claims to have repeatedly eaten salads. The German naturalist Friedrich Martens (1635–1699) visited in 1671 traveling aboard a ship christened Jonah in the Whale. His 1675 report of the journey, Spitzbergische oder Groenlandische Reise-Beschreibung, included the first scientific description of the flora and fauna of Svalbard and became an oft-cited reference work. In Martens’ eyes, Smeerenburg was a “village”.1 Chronicles escalated from there, particularly as their authors ceased visiting the settlement themselves.

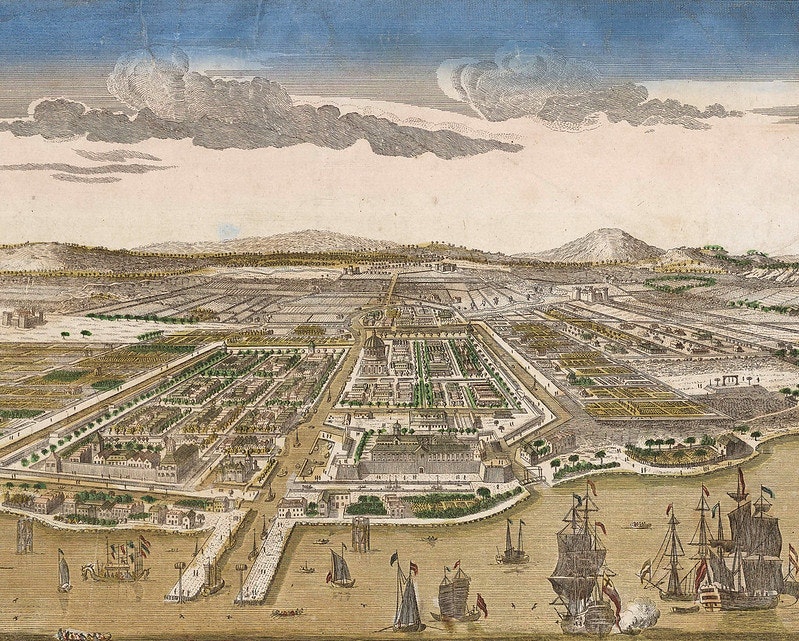

By the eighteenth century, written accounts make clear that Smeerenburg was abandoned, but the myth of its former grandeur continued. Cornelis Gijsbertsz Zorgdrager penned what is considered the first classic account, influencing dozens of authors. Writing in 1720, Zorgdrager assures his reader that he is using reliable information from informants whose kin sailed to the whaling station when the Noordsche Compagnie was master of the trade. Zorgdrager upgrades the settlement from “village” to a “half small city” with busy streets.2 In addition to the tryworks that contained the ovens and working platforms, dwellings, warehouses, and workshops crowd the peninsula in his telling. Peddlers offer a variety of wares including tobacco and spirits in street-side stalls. According to Zorgdrager, Smeerenburg was a destination to make a “good purchase”.3 Best of all, Smeerenburg was home to multiple bakers. Each morning, when they pulled their bread hot from the oven, a horn was blown to alert the weary whalers. For this reason, Zorgdrager is tempted to compare Smeerenburg with Batavia, then the humming capital of the Dutch East Indies, but demurs based on the number of anchored ships reported.

Over time, the purported size of Smeerenburg grew larger as the myth propagated. English explorer William Scoresby, whom Herman Melville’s Ishmael quotes in Moby-Dick, introduces false numbers into the legend. In his popular 1820 Account of the Arctic Regions, Scoresby (1789–1857) asserts “the place had the appearance of a commercial or manufacturing town.”4 Leaning on the Batavia comparison mentioned by Zorgdrager and elaborated upon by other writers, Scoresby has no problem repeating the invention of shopkeepers, artisans, and bakers, ultimately calculating the population between 12,000 and 18,000 people. For comparison, at the time of the American Revolution, Boston had 15,000 residents. Building on Scoresby’s description, other authors add churches, fortresses, wood-paneled houses in bright colors, and even enlarge the size of buildings to 80 by 50 feet. By the end of the century, the rocky coast was thought to have been packed full and the harbor teeming with ships.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Detail from a late 18th-century depiction of Batavia — Source.

The most colorful accounts come from the twentieth century. Surprisingly, the otherwise meticulous Norwegian scientist Fridtjof Nansen, famous for crossing Greenland, perpetuated and inflated the myth. In A Voyage to Spitsbergen (1920), Nansen claims:

Here was an whole town with booths and streets . . . . Some ten thousand people in the summer with the clamor of pack-stalls, and oil cookeries, and gambling halls, of smithies, and workshops, of peddlers, and dance halls. Along this flat beach, a mass of boats with seafarers just coming from the exciting whale-hunt, and of women in various colors who were on the man-hunt.5 Nansen likely read the earlier texts by Zorgdrager and Scoresby; though, it is unclear whether he had a source for the addition of lusty women and dance halls. Regardless, relying on Nansen as a respected researcher, others soon ran with the idea. Helge Ingstad, who with his wife Anne Stine discovered the remains of a Viking settlement in Canada, repeats the extravagant tale of Smeerenburg in his 1948 book The Land with the Cold Coasts. Ingstad discusses the shops, dwellings, and church and further adds a “house for loose women”.6 As late as 1984, the Norwegian Svalbard Society released a history of the archipelago that cited the bakeries of Smeerenburg and estimated its population reached up to 18,000 men.

In reality, Smeerenburg was never more than a desolate outpost. Thanks to the enduring myth, considerable archaeological work was conducted on Amsterdamøya between 1979 and 1981. Some estimate the maximum number of men to have been two hundred at any given time — and there is no evidence of women on the site. There may have been a total of nineteen buildings, including warehouses and workshops, where craftsmen, blubber cutters, and blubber cooks worked. At most there were eight oil cookeries. There was no church or gambling den. The focus was unambiguously on work and capitalizing on the short hunting season. The conditions were grueling. Men likely worked long hours, taking advantage of the endless Arctic summer days, often working through the night in rotation. Zooarchaeological analysis suggests the Dutch were primarily dependent on barreled beef in the seventeenth century. Transported from the Netherlands, the meat would have been cut into 25-centimeter portions, salted, and packed in casks. Jacob Segersz van der Brugge’s fox meat was the exception. And his much-rhapsodized “salad” was likely fistfuls of cochlearia officinalis. Better known as scurvygrass, the leafy plant did indeed ward off the disease, but had an impossibly bitter taste. Eventually, shelters were built by the ovens to protect workers from inclement weather. But death was not uncommon. 101 graves have been identified on the island.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Dutch Whalers near Spitsbergen (1690), by Abraham Storck — Source.

By the 1660s, Smeerenburg was a ghost town. The Noordsche Compagnie dissolved in 1642 after Dutch free traders created too much competition for the cartel. Further precipitating the decline of Blubber Town, whales all but vanished from the coasts of Svalbard. The animals began avoiding the waters either due to shifting currents or learned wariness of the area. With whales further out at sea, it became unnecessarily difficult to drag them to shore — particularly to an island isolated in the upper reaches of the Arctic. Consequently, the Dutch abandoned shore whaling for pelagic whaling, flensing slain whales alongside ships and returning to port in the Netherlands with unprocessed blubber. Vaguely aware of this history, some chroniclers warned against tales of a bustling Blubber Town. Already in his 1874 study of the Noordsche Comagnie, Samuel Muller names them “fairytales”.7

Nevertheless, the myth persisted and grew over time. One explanation, of course, is simply bad history. Authors stopped visiting the settlement themselves and depended solely on first- and second-hand reports. Eventually, these sources disappeared. Writers had to rely on previous written accounts of Smeerenburg and a combination of misreadings and embellishments twisted into an elaborate yarn. A long series of even small exaggerations eventually produced imaginary dance halls and brothels.

Alternatively, it is possible that authors like Scoresby and Nansen strategically deployed the far-fetched stories to attract readers interested in the fantastic. This feels unlikely though. Whaling itself was exciting business, full of enthralling adventures (as Moby-Dick makes clear) — there would be no need to invent a town to capture the imagination of common readers. In any case, evidence indicates the earliest published sources relied on sailors’ tales; the myth was not simply the invention of profit-seeking scribes.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Facsimile of a woodcut in the La cosmographie universelle d’André Thevet (1574) — Source.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Facsimile of a woodcut in the La cosmographie universelle d’André Thevet (1574) — Source.

A more generous interpretation, perhaps, is that historians projected their current situation onto the past. After the disbandment of the Noordsche Compagnie in 1642, the number of Dutch whaling ships rapidly increased from some 35 to 70 in 1654 and 148 ships by 1670. Unregulated free whaling burst open the industry and the Dutch continued to outpace competitors until the second half of the eighteenth century. The whale trade itself did not slow down until the twentieth century. By 1840 there were more than seven hundred whaling ships throughout the world. It is possible that authors like Scoresby failed to appreciate how much the industry had grown after Smeerenburg’s abandonment, concluding the settlement must have been crowded when land-based processing was practiced in the seventeenth century. Others may have wrongly assumed all Dutch colonial ports were similar. Coincidentally, the Dutch East India Company razed Jayakarta and founded Batavia in 1619, the same year permanent dwellings were built on Amsterdamøya. Authors like Zorgdrager and Scoresby, who compared the whaling station with the still-flourishing Batavia, might also have sought to glorify the Dutch Republic’s reach and riches by inflating the size and splendor of Smeerenburg.

The sailors who spread stories about Blubber Town likely had a different objective. Throughout the years, whaling remained both tedious and dangerous. The shift to open-sea whaling meant most men did not step foot on land for months. Quarters aboard a typical ship were damp, crowded, and typically under five feet high. In such conditions, dreams of warm beds and quaint cottages would naturally fill even the most sober heads. Daily servings of barreled beef might conjure illusions of freshly baked bread. And the monotony of working with the same crew could inspire longings for gambling dens and dance halls to meet new people. The fantasy of a Blubber Town brothel requires no explanation. Especially for men tricked or coerced onto ships, as was not uncommonly the case, such an imaginary town enabled hopes of a getaway, particularly in the Arctic, where there was no place to flee. Stories about Smeerenburg might have been a foil that allowed later whalers to feel justified bemoaning their comparably harder lot. But ultimately, like many myths, Blubber Town was meant to entertain, to provide an escape for readers at sea and at home alike.

Surrounded by steep mountains, glacier walls, and deep fjords, Smeerenburg is now a popular stop for Arctic cruises. In 1973 its ruins became part of Norway’s Nordvest-Spitsbergen national park. Visitors are warned against walruses and then invited to wonder at the brick foundations of the tryworks. They can gape at the so-called “blubber cement” that still outlines the place where enormous cooking vessels once stood. The result of mixed whale oil, sand, and gravel, the asphalt-like substance is the most tangible remnant of Blubber Town. Otherwise, the busy streets, warm bread, and welcoming women populating Smeerenburg must continue to exist in our collective imagination.

Matthew H. Birkhold is the author of Characters before Copyright (Oxford University Press, 2019) and is currently writing a cultural history of icebergs. More at matthewhbirkhold.com.