Brilliant Visions Peyote among the Aesthetes

Used by the indigenous peoples of the Americas for millennia, it was only in the last decade of the 19th century that the powerful effects of mescaline began to be systematically explored by curious non-indigenous Americans and Europeans. Mike Jay looks at one such pioneer Havelock Ellis who, along with his small circle of fellow artists and writers, documented in wonderful detail his psychedelic experiences.

July 25, 2019

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

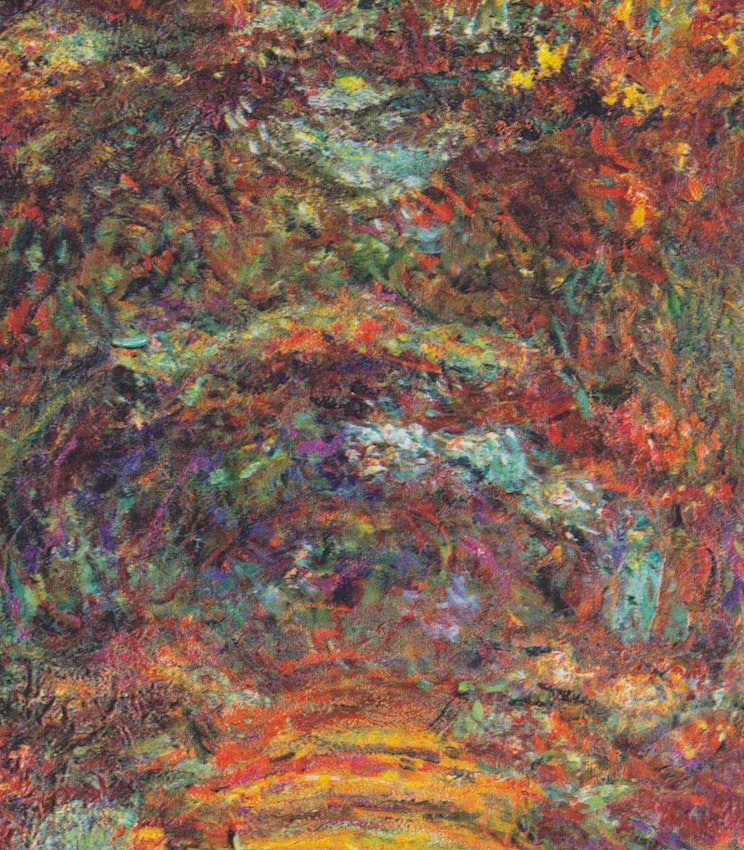

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Detail from The Rose-Way in Giverny (ca. 1920) by Claude Monet — Source.

On Good Friday of 1897, the art critic and littérateur Havelock Ellis wrote, “I found myself entirely alone in the quiet rooms in the Temple which I occupy when in London, and judged the occasion a fitting one for a personal experiment.”1 Ellis was staying, as he often did, in the rooms rented by his friend Arthur Symons, the literary critic and decadent poet, in Fountain Court, a red-brick mansion block by the Thames among the barristers’ chambers with which the area is still associated. The experiment in question was the first in Britain with the hallucinogenic peyote cactus, from which a German chemist named Arthur Heffter was at this moment isolating the first psychedelic drug known to science, mescaline.

Ellis had been alerted to peyote’s “brilliant visions” by a vivid report from America’s leading neurologist, Silas Weir Mitchell, which appeared in the British Medical Journal in December 1896.2 He was intrigued enough to seek out the cactus and discovered that its dried buttons could be obtained from Potter & Clarke, the London pharmacists best known for “Potter’s Asthma Cure”, a greenish powder that contained the dried leaves of the highly toxic datura plant.

Having acquired his sample, Ellis proceeded to make a liquid decoction of three buttons which he drank slowly in Symons’ apartment over two hours. He began to feel faint, his pulse weakened, and he lay down to read. As Mitchell had done, he first noticed the visual effects as they impinged on the note-taking process: “a pale violet shadow floated over the page around the point at which my eyes were fixed”. As evening closed in he was gradually enveloped, just as Mitchell had been, by “a vast field of golden jewels, studded with red and green stones, ever changing.” From this point on “the visions continued with undiminished brilliance for many hours”.3

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

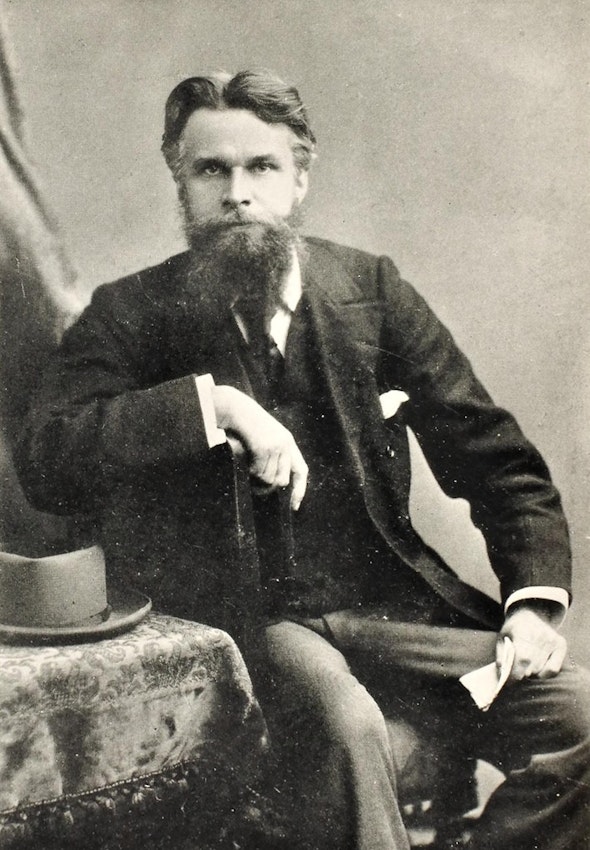

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Photograph of Ellis in the year he published “Mescal: A New Artificial Paradise”, from Havelock Ellis: A Biographical and Critical Survey (1926) by Isaac Goldberg — Source.

Ellis was a qualified doctor, and his first report on peyote was a short article in the 1897 June issue of the Lancet that concentrated on its physical effects. But his interest in the experiment extended well beyond medicine. He was an example of the modern Renaissance man he had called for in his 1890 book The New Spirit, the manifesto for a movement in which the arts, sciences, politics, and religion would all be reinvented and rejoined. He was in the process of writing, in correspondence with the art historian and advocate of “male love” John Addington Symonds, the taboo-shattering multi-volume study of sex that would become his enduring achievement. He was an individualist and a feminist, a member of the Progressive Association and an intimate of London’s tightly-knit fin-de-siècle artistic coterie. The much longer account of his peyote trip that he published in January 1898 in a progressive literary quarterly, the Contemporary Review, presented the aesthetes of the fin de siècle with an original and exquisite portrait of the psychedelic experience.

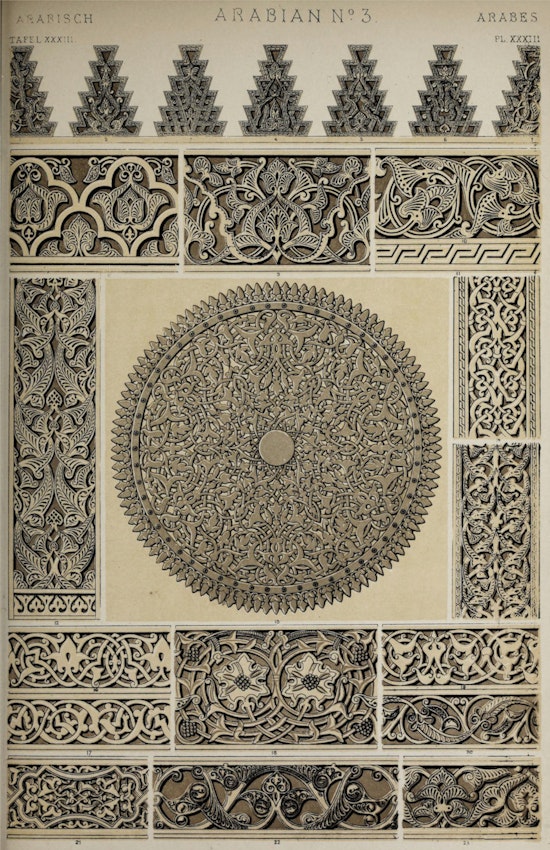

Its title, “Mescal: A New Artificial Paradise”, announced its line of descent from Charles Baudelaire’s 1860 essay on hashish, Les paradis artificiels — along with the masterwork of Baudelaire’s hero Thomas De Quincey, Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, the nineteenth century’s most admired literary account of a drug experience. The previous year Ellis had written a paper on “The Colour Sense in Literature”, comparing the imagery invoked by authors such as Shakespeare, Chaucer, Coleridge, Poe, and Rosetti.4 Now he brought a similar sensibility to bear on the peyote cactus. Every part of the colour spectrum competed in his visions, he wrote, and yet “there was always a certain parsimony and aesthetic value” in their combinations. He was “further impressed, not only by the brilliance, delicacy, and variety of the colours, but even more by their lovely and various textures — fibrous, woven, polished, glowing, dull, veined, semi-transparent”. He compared the patterns that formed and dissolved to the “Maori style of architecture” and “the delicate architectural effects as of lace carved in wood, which we associated with the moucrabieh work of Cairo”. They were “living arabesques”, constantly in flux yet with “a certain incomplete tendency to symmetry, as though the underlying mechanism was associated with a large number of polished facets”.5

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.“Arabian Ornaments of the Thirteenth Century from Cairo”, plate 32 from Owen Jones’ The Grammar of Ornament (1865) — Source.

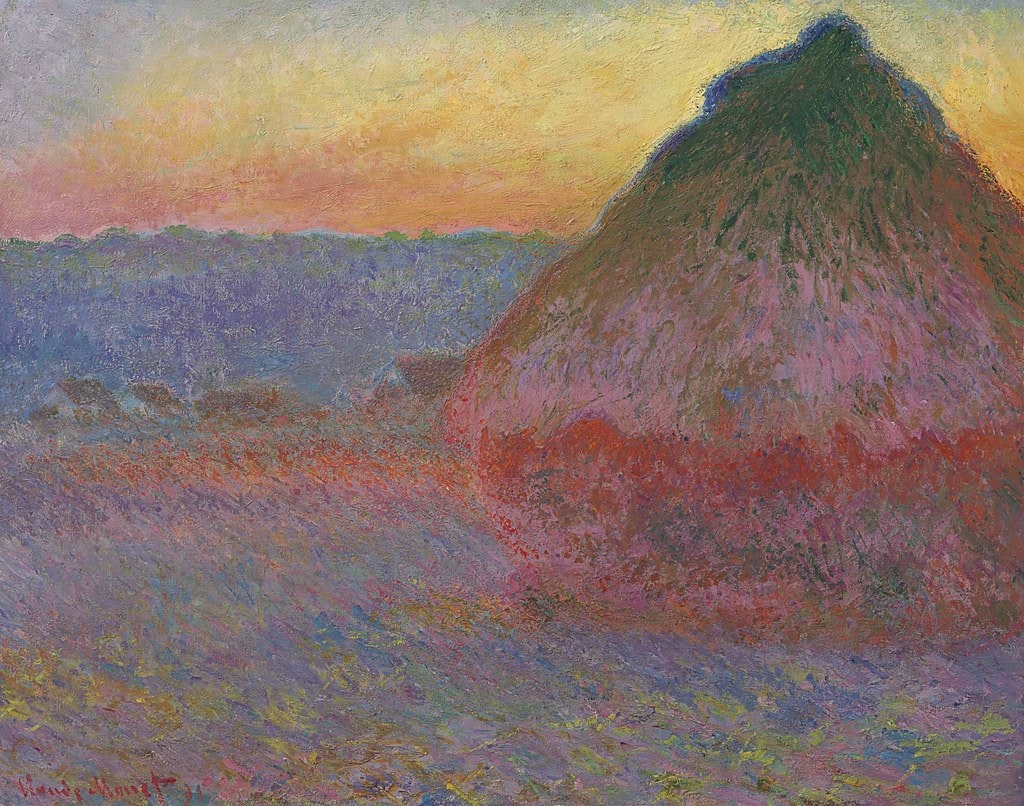

When Ellis became exhausted by the visions in darkness, he turned on the gas light. The shadows that leapt to life reminded him of the “visual hyperaesthesia” of Claude Monet’s paintings. Peyote was a feast for the eyes, and an education for them. Writing up the experience some months later, he maintained that “I have been more aesthetically sensitive than I was before to the more delicate phenomena of light and shade and colour”.6

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Grainstack in the Sunlight (1891) by Claude Monet — Source.

Ellis’ report was the flowering of a tendency that established itself immediately in western encounters with psychedelics: to describe their effects primarily in visual terms. This “ocularcentricity” has been seen as a characteristic of western modernity in general — it is far less prominent in indigenous descriptions of peyote — but it was also a specific response to the fin-de-siècle moment at which peyote made its appearance. The critic and philosopher Walter Benjamin, who would himself take mescaline in a clinical trial in 1934, wrote that the nineteenth century “subjected the human sensorium to a complex kind of training.”7 Visual illusions — from kaleidoscopes to magic lanterns to photography — made the transit from dazzling novelties to staples of mass culture. Magicians, mediums, and psychic investigators all probed the limits of the real, blurring the line between optical trickery, the subconscious mind, and the spirit world. At the moment when Ellis made his experiment, the world was being exposed for the first time to X-ray images and the cinematograph. “Visual hyperaesthesia” was a symptom not only of peyote but of the culture in which he was consuming it, and to which Monet and the impressionists were responding.

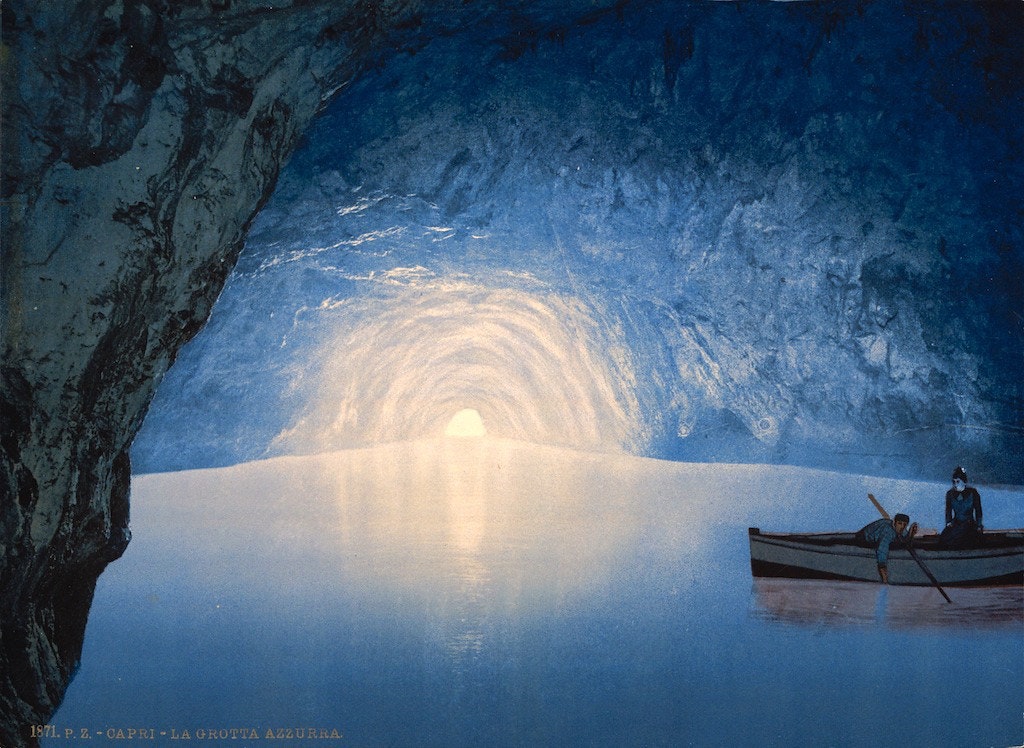

Ellis’ immediate circle exemplified this hunger for visual sensation, and his enthusiasm brought into being mescaline’s first informal artistic and literary scene. Curious as to what an artist would make of mescal, he persuaded one of his acquaintances to try it. The first dose was too weak and the second far too strong, inducing, in his friend’s words, “a series of attacks or paroxysms, which I can only describe by saying that I felt as though I was dying.” Visions alternated with strange and disturbing physical sensations, and sometimes combined with them: when Ellis passed him a piece of biscuit to relieve his nausea, it “suddenly streamed out into blue flame”, an electric conflagration that spread across the right-hand side of his body. “As I placed the biscuit in my mouth it burst again into the same coloured fire and illuminated the interior of my mouth, casting a blue reflection on the roof. The light in the Blue Grotto at Capri, I am able to affirm, is not nearly as blue as seemed for a short space of time the interior of my mouth.”8

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Blue grotto, Capri Island, Italy (ca. 1900), from the Detroit Publishing Company — Source.

Ellis made a further experiment on himself to test the effects of music, and found that when a friend played the piano “the music stimulated the visions and added greatly to [his] enjoyment of them.”9 He also “made experiments on two poets, whose names are both well known” and can be identified with reasonable certainty as his friends W. B. Yeats and Arthur Symons. Throughout 1896 Symons had edited the short-lived but influential Savoy magazine, with Aubrey Beardsley as illustrator and both Ellis and Yeats among the contributors. While Ellis was reading Weir Mitchell’s account of peyote in December 1896, the pair were taking hashish together in Paris.

The first subject, presumably Yeats — a poet “interested in mystical matters, an excellent subject for visions” — was impaired by a weak constitution. “He found the effects of mescal on his breathing somewhat unpleasant; he much prefers hasheesh”. But Symons, on a modest dose of a little under three buttons, was transported. “I have never seen such a succession of absolutely pictorial visions with such precision”, he reported. Dragons balancing white balls on puffs of their exhaled breath swept past him from right to left. Playing the piano with closed eyes, he “got waves and lines of pure colour”.10

Late in the evening, Symons walked from Fountain Court down to the Thames embankment. As he gazed across the river at the south bank, he found himself “absolutely fascinated by an advertisement of ‘Bovril’, which came and went in letters of light on the other side of the river”.11 The brilliance of electricity was a recurring metaphor for peyote’s scintillating visions: the very first subject in the initial scientific trials in the United States in 1895 had compared them to the dazzling electric illuminations he had witnessed at the Chicago World’s Fair two years previously. But it was a literal stimulus too. It seemed that nothing delighted the eye of the modern mescal eater so much as the new electrical sublime. They arrived together as avatars of a future world of visual spectacle, equal parts scientific discovery and aesthetic delight.

Mike Jay has written extensively on scientific and medical history and contributes regularly to the London Review of Books and the Wall Street Journal. His latest book is Psychonauts: Drugs and the Making of the Modern Mind, and his previous books on the history of drugs include Mescaline, High Society, and The Atmosphere of Heaven.

This essay has been adapted from a section in Mike Jay’s Mescaline: A Global History of the First Psychedelic published by Yale University Press in 2019.