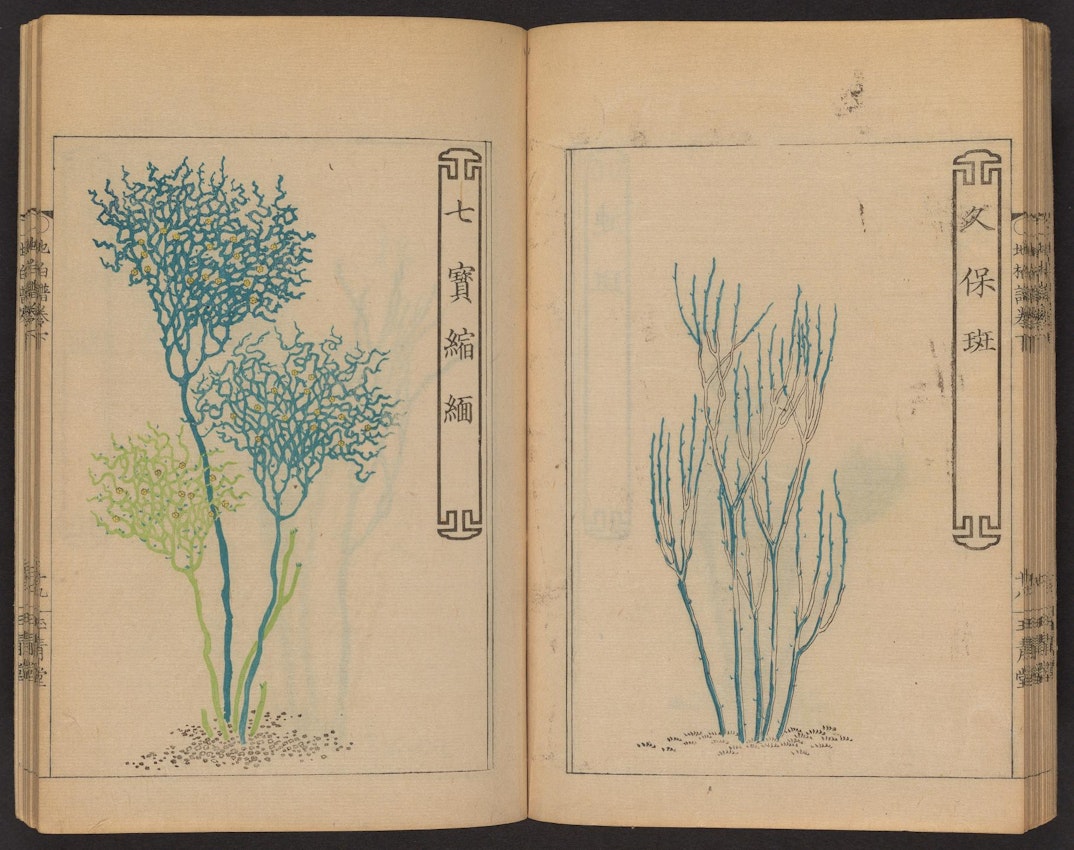

A Careful Selection of Whisk Ferns (1837)

Of the aesthetic imperfections to be avoided by any serious practitioner, the 1989 guide Classic Bonsai of Japan lists kuruma-eda (“branches that originate from a single point”) and karami-eda (“branches . . . whose lines cross each other”), as well as vessels that are too-showy, attempts to make species like the gingko curve as they grow, and improper balance in the “twin-trunk style”. Such modern handbooks find their ultimate antecedents in the Tokugawa Period, when fans of these miniature trees included even the era’s namesake warlords — indeed, a five-needle pine said to have been nursed by the shōgun Tokugawa Iemitsu himself is still living to this day (despite its near-totally hollow trunk) and has been declared a national treasure by the Japanese state. Robert J. Baran, researcher and historian for the Phoenix Bonsai Society, writes that the earliest catalog of bonsai was likely Chōseisha Aruji’s Manual on Arboriculture (Kinsei jufu), published in 1833. The appearance of these books on the market accompanied both a terminological and a categorical shift: from hachi-no-ki (literally, tree in a pot) to the name we now know today, and from a merely decorative role to something that took on the physical and philosophical rigors of artistic practice.

Contemporary books on the subject were accompanied by delicately rendered illustrations of thick foliage, curved branches, and rugged trunks, with particular care lavished on the exquisite ceramic pots from which bonsai itself (the first character of which means tray) takes its name. In contrast, this curious two-volume illustrated book on bonsai from 1837 dispensed not only with the vessels but with the trees themselves. That set, A Careful Selection of Whisk Ferns (Seisen Matsuranfu), is devoted instead to the cultivation of the titular rootless, branchless, leafless genus, whose smooth stems are stippled here and there with globular yellow outgrowths called enations. The images dedicated to these minimalist beings, in lime and emerald green, seem to reduce bonsai to its sparest visual elements. The result is something alien, algal — hardly recognizable as a plant at all.

Whisk ferns — Psilotum to botanists, matsubaran in Japanese — belonged to a category of plants called kihin, curious and rare specimens for which there was a fad among collectors during the latter part of the Tokugawa Shogunate. Printed illustrations could forever freeze these unique cultivars in the moment of their highest flowering or fullest leaf. But publishers of books who fed into the kihin craze sometimes ran afoul of the period’s harsh sumptuary laws, which strictly regulated the consumption and display of luxury items according to one’s social status. Such is the case for Catalogue of Extraordinary Plants (Sōmoku Kihin Kagami), whose unfortunate editor, Kinta the Gardener, had his property seized and his woodblocks burned before being banished from the capital forever — fitting punishment, so it was apparently thought, for promoting such dangerous indulgences.

Sep 19, 2023