D. A. Rovinskii’s Collection of Russian Lubki (18th–19th Century)

The origins of the Russian prints called lubki (singular lubok) appear to stretch back to the 1500s, when the art of block printing was introduced to Russia from Eastern Asia, around the same time German Hanseatic merchants brought the first printed books to Moscow. As Adela Roatcap remarks:

The Biblia Pauperum, the Ars Morendi, the Piscator Bible, the 1514 Wittenberg Bible, or the Nuremberg Chronicle, and engraved prints by Lucas Cranach, Albert Dürer and other Western European artists, supplied inspiration for the earliest lubki.

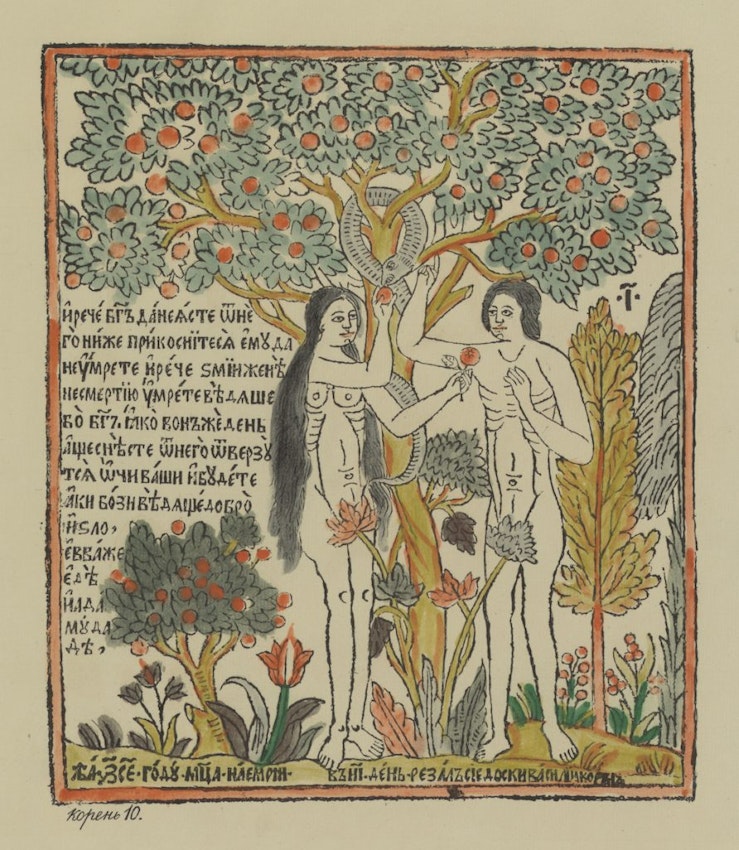

The oldest surviving lubki, according to Roatcap, were printed in Kiev (present-day Ukraine) in 1625 and depicted Orthodox religious figures and scenes. Indeed, lubki are thought by many scholars to have first gained popularity as a cheap substitute for religious icons and were used by people of the lower and middle classes to decorate the walls of homes and taverns.

The lubki featured here are from the collection of Dimitrii Aleksandrovich Rovinskii, a high-ranking jurist in nineteenth-century Moscow, who devoted his spare time to his greatest passion, Russian folk art. In 1881 he published the first instalment of his twelve-volume Russian Folk Pictures, displaying reproductions of his collection along with commentary — a book which has now been digitized and made available online by the New York Public Library. In the book, unsurprisingly, one finds no small number of religious themes.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing."Kartiny iz Biblii i Apokalipsisa, raboty mastera Korenia" [Painting from the Bible and the Apocalypse, by Master Root]

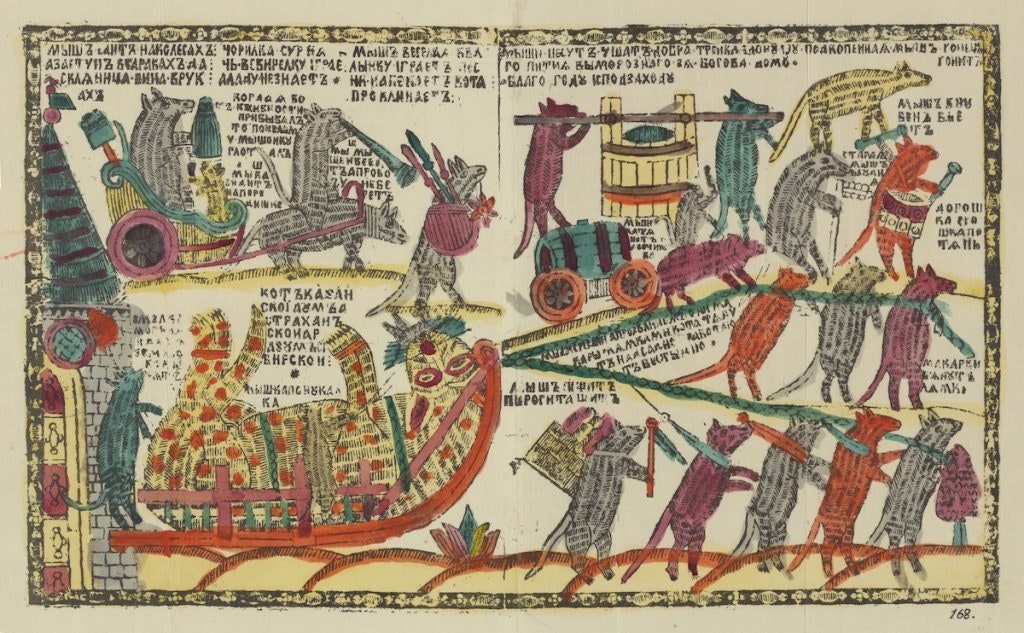

But there is also plenty of secular subject matter. Probably two of the most famous of these secular prints are of cats. The first is the 1760s lubok titled The Mice Are Burying the Cat — a carnivalesque scene making fun of Russia’s emperors and empresses. The caption above the cat reads: “The Cat of Kazan, the Mind of Astrakhan, the Wisdom of Siberia” (parodying the elaborate title of the Russian leader).

"Myshi kota pogrebaiut (graviura na dereve)" [The Mice Are Burying the Cat]

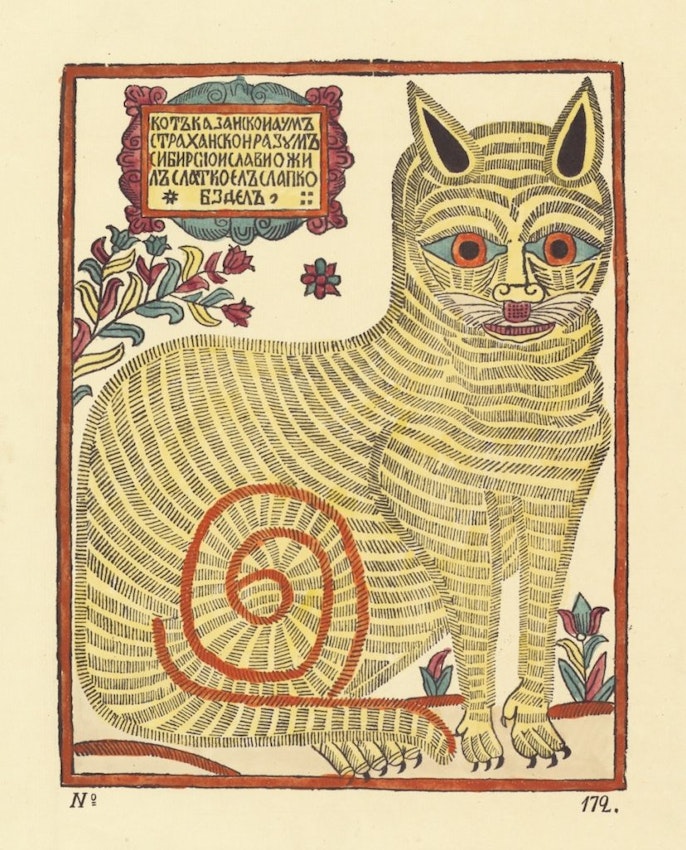

The second is titled simply Cat (or The Cat of Kazan) and is sometimes attributed to the artist Vasili Loren (see lead print above). Here, again, the subject is ostensibly one of Russia’s leaders — Peter the Great, who, after a trip to Louis XIV’s clean-shaven court, issued an edict forcing Russians either to cut off their beards or pay an annual tax. The caption above the creature’s head reads: “The Cat of Kazan, in the manner of Astrakhan, by reason of Siberia, lives gloriously, manages agreeably, and farts sweetly.”

The “spirit of medieval popular humor,” in the words of scholar Dianne Ecklund Farrell, permeates these colorful forerunners of comic strips. A fascination with animals, monsters, and caricatured human figures is everywhere evident. While we non-Russian-readers don’t always know exactly what’s going on in the prints, we are impressed and delighted by them nonetheless.

Scroll through our selection of Rovinskii’s lubki below, or browse the whole digitized collection here, in the NYPL Digital Collections.

"Gromadnyi kot." [Big Cat], 1881.

"Obez'iana uchitel' peniia." [Monkey Music Teacher [?]]

"Satira na vysokuiu prichesku." [Satire of a hairstyle]

"Izobrazhenie Satira, pokazyvavshagosia v Ispanii, v 1760 godu." [Satyr Shown in Spain, 1760; for more information on this image, see this blog post.]

Front cover of a Divination Book.

"Zhivotnoe, naidenoe v Ispanii, 27 Ianvaria 1775 goda". [An Animal Found in Spain, January 27th 1775].

"Raiskaia ptitsa Sirin". [Bird of paradise Sirin].

"Dva duraka vtroem." [Two Fools]

"Reitarsha na kuritse." [Chicken Rider], 1881.

Garpiia [Harpy]

Pomekha v liubvi. [A hindrance to love]

Baba- Iaga deretsia s krokodilom. [Baba Yaga fights a crocodile]

Imagery from this post is featured in

Affinities

our special book of images created to celebrate 10 years of The Public Domain Review.

500+ images – 368 pages

Large format – Hardcover with inset image

Nov 12, 2019