Fabre’s Book of Insects (1921)

In the first chapter of this condensed and beautifully illustrated English version of his ten-volume series on insects, Jean-Henri Fabre (1823–1915) introduces the reader to his workshop — which is to say his home — located on a pebbly expanse of land near the Provençal village of Sérignan du Comtat, “where hardly any plant but thyme can grow”. This might seem an unpromising setting for a naturalist, but for Fabre nothing could have been more suitable than this “happy hunting-ground of countless Bees and Wasps”.

Never have I seen so large a population of insects at a single spot. All the traders have made it their centre. Here come hunters of every kind of game, builders in clay, cotton-weavers, leaf-cutters, architects in pasteboard, plasterers mixing mortar, carpenters boring wood, miners digging underground galleries, workers in gold-beaters’ skin, and many more.

If you have already lost track of whether Fabre is talking about insects or people here, you are not alone. His ten-volume Souvenirs entomologiques, or Entomological Memoirs, made Fabre famous in France and abroad not only as a populariser but as a humaniser of insect life. He was respected as an ethologist (one who studies animal behaviour) by his fellow scientists: Charles Darwin, whose theory of evolution Fabre would vociferously oppose, cited him as an “inimitable observer” in both The Origin of the Species and The Descent of Man. But he was beloved by readers and writers: Victor Hugo dubbed him the Homer of the Insect World.

Like Jacques Cousteau in the twentieth century, Fabre’s greatest accomplishment was perhaps to have brought out the beauty and drama in the lives of creatures that had hitherto been regarded with horror, if regarded at all. He turned his attention not just to bees, whose praises have of course been sung since the classical era, but to wasps, weevils, ants, glow-worms, caterpillars, and cicadas. He also sometimes wrote about wild flora and fauna, and in one rare chapter about his cats — all in prose characterized, a little like Cousteau’s, by a well-informed wonder at the natural world, appealing to both children and adults:

Few insects enjoy more fame than the Glow-worm, the curious little animal who celebrates the joy of life by lighting a lantern at its tail-end. We all know it, at least by name, even if we have not seen it roaming through the grass, like a spark fallen from the full moon. The Greeks of old called it the Bright-tailed, and modern science gives it the name Lampyris.

Fabre’s Book of Insects, however, is geared specifically toward children. The texts here have been taken from Alexander Teixeira de Mattos’s unabridged translations of the Entomological Memoirs and “retold” (abridged and significantly revised, if not outright bowdlerized) for a young readership by Mrs Rodolph Stawell — the author of, among other things, Fairies I Have Met.

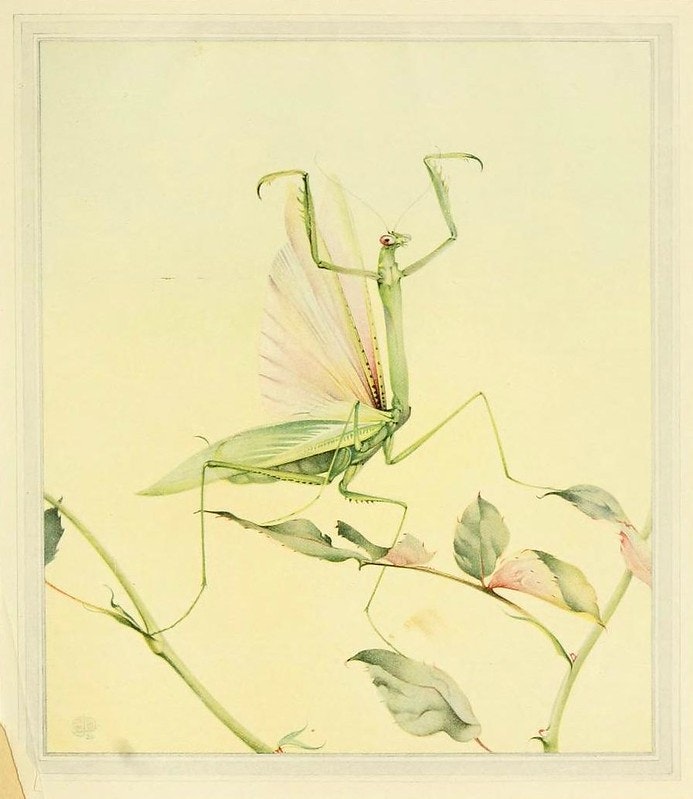

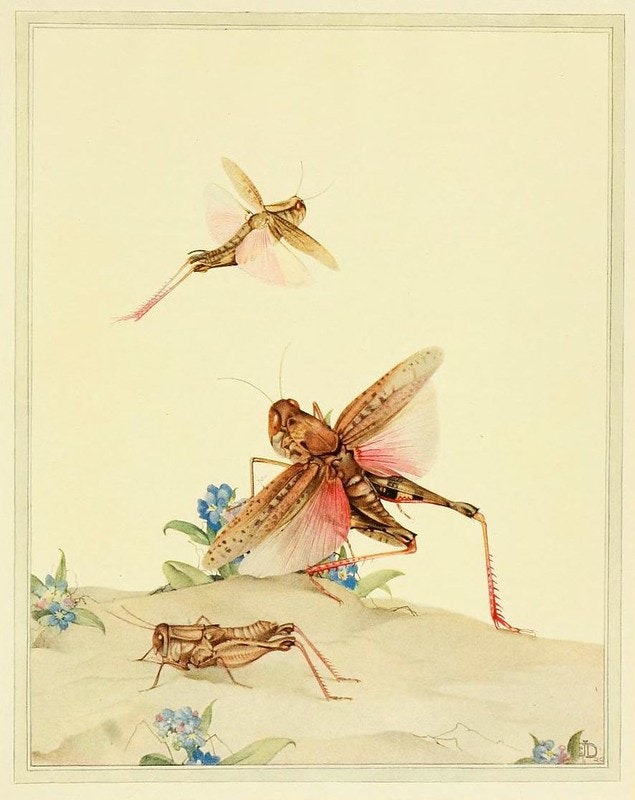

The illustrations by E. J. Detmold (who also provided pictures for Maeterlinck’s The Life of the Bee and W. H. Hudson’s Birds in Town and Village) likewise emphasize the whimsy in Fabre’s accounts of our six-legged neighbours. The “Sacred Beetle” is shown working “in partnership with a friend”; the praying mantis is depicted in the middle of her deathly dance; and an Italian locust, with very long legs, appears to be enjoying herself enormously as she buries her eggs in the dirt.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.The Sacred Beetle

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.The Praying Mantis

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Italian Locusts

You can find more of Detmold’s illustrations below, and discover all of Texeira de Mattos’s (unabridged) translations of Fabre’s Entomogical Memoirs here.

The Anthrax Fly

The Sisyphus

The Field Cricket

Common Wasps

The White-Faced Decticus

The Spanish Copris

Pelopaeus Sprifex

The Cicada

Jul 4, 2019