The Beast of Gévaudan (1764–1767)

In the 1760s, nearly three hundred people were killed in a remote region of south-central France called the Gévaudan (today part of the département of Lozère). The killer was thought to be a huge animal, which came to be known simply as “the Beast”; but while the creature’s name remained simple, its reputation soon grew extremely complex. Not only was the Beast of Gévaudan said to prefer attacking women and children (and above all small girls), according to firsthand accounts published in the press it often “removed the victim’s head and drank all her blood”, leaving nothing behind but a pile of bones.

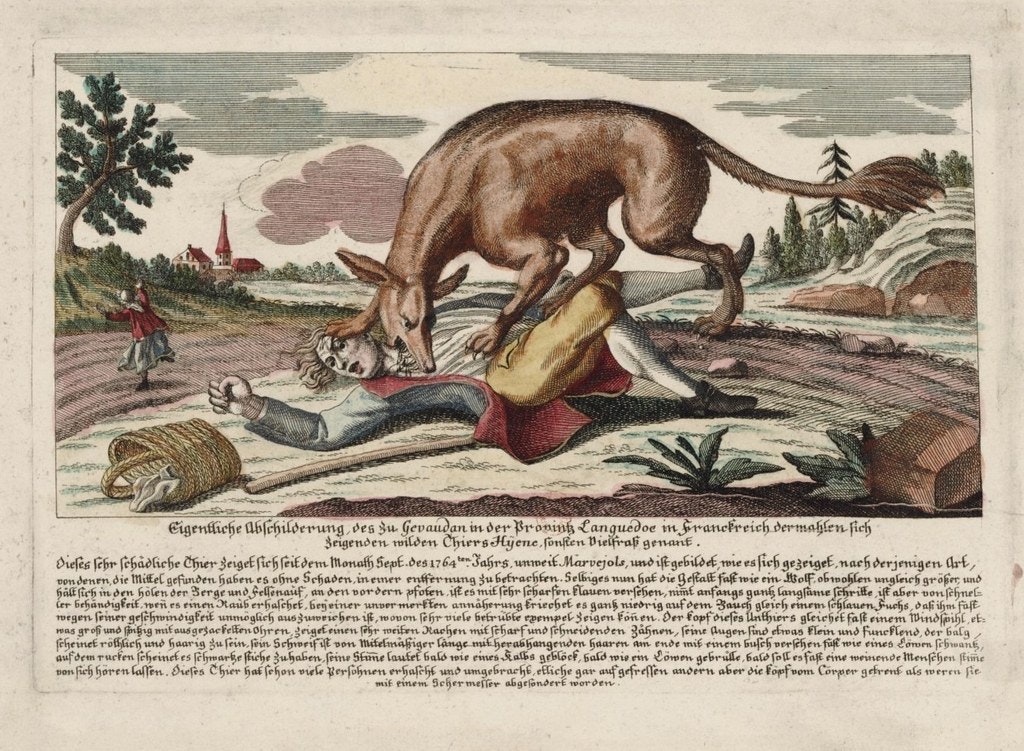

Illustrators had a field day representing the Beast, whose appearance was reported to be so monstrous it beggared belief. One poster, printed in 1764, described it as follows:

Reddish brown with dark ridged stripe down the back. Resembles wolf/hyena but big as a donkey. Long gaping jaw, six claws, pointy upright ears and supple furry tail — mobile like a cat’s and can knock you over. Cry: more like horse neighing than wolf howling.

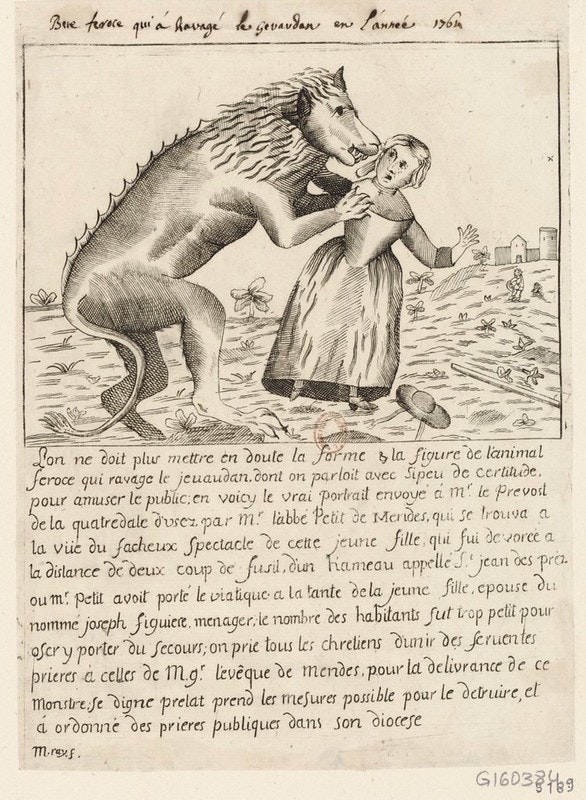

Another print (see below), probably published the same year, bears the caption: “Picture of the monster desolating the Gévaudan, This Beast is the size of a young Bull, it likes to attack Women and Children, it drinks their Blood, cuts off their Heads, and carries them off.” A reward of twenty-seven hundred livres is promised to whoever brings the animal down.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.“Picture of the monster desolating the Gévaudan", ca. 1764 — Source.

The rampage of the Beast of Gévaudan was one of the first international news stories. First breaking in the Courrier of nearby Avignon, it was quickly taken up by the papers of Paris and from there spread abroad. A German print from September 1764 shows the Beast, looking more like a quadrupedal kangaroo than a wolf or hyena, attacking an improbably well-dressed man in a rather Teutonic-looking landscape.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.German print of the Beast, 1764 — Source.

Many artists emphasized the goriness of the Beast’s eviscerating attacks, as in this French illustration published by Mondhare in Paris.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.18th-century print depicting the Beast — Source.

Many also emphasized the Beast’s preference for feminine victims. In this engraving by the French printer M. Ray, which depicts the beast as a semi-erect reptilian lion, the text assures us that “There can no longer be any doubt regarding the appearance of the ferocious animal ravaging the Gévaudan”.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.The Beast in a print by M. Ray — Source.

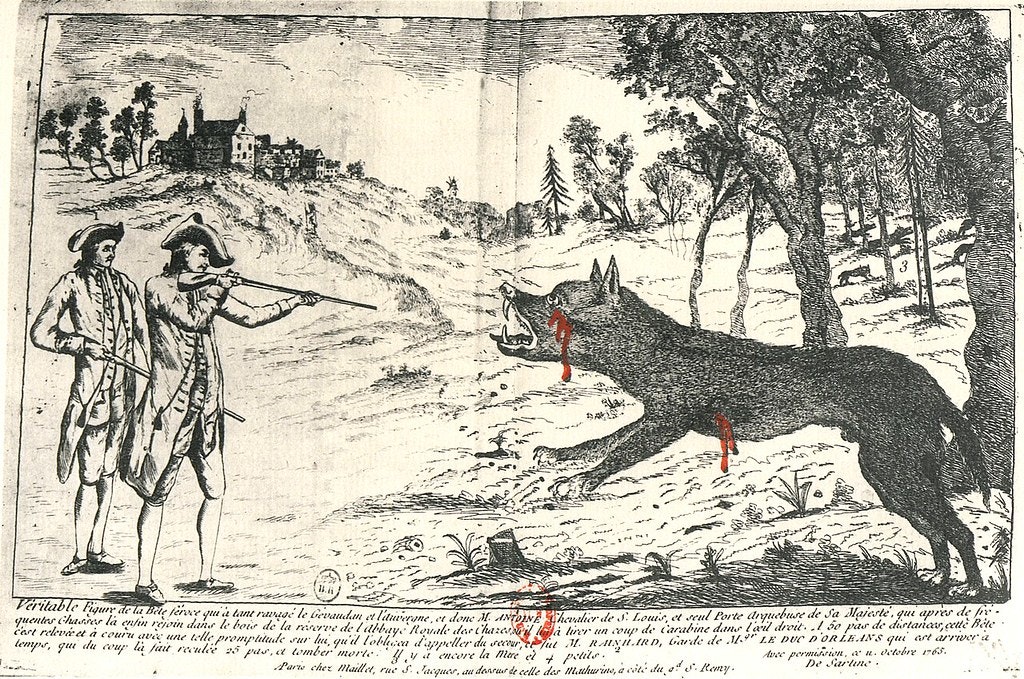

By the winter of 1764–1765, the attacks in the Gévaudan had created a national fervor, to the point that King Louis XV intervened, offering a reward equal to what most men would have earned in a year. Tens of thousands of hunters descended on the region. King Louis also deployed a dragoon captain, named Jean-Baptiste Duhamel, and a number of royal troops. Yet neither the swarms of hunters, nor Duhamel, nor the pair of professional wolf stalkers Louis eventually sent to replace Duhamel, were able to track down the animal responsible. It was not until September 1765 that François Antoine, Louis’ lieutenant of the hunt, shot the enormous “Wolf of Chazes”, which was stuffed and put on display in Versailles.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.François Antoine shooting the Beast in September 1765, printed in Paris, 1765 — Source.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.The Wolf of Chazes displayed at Versailles, printed in Paris, 1765 — Source.

Although Antoine also killed the wolf’s similarly enormous mate and cub, the attacks continued. But by now the Royal Court had lost interest. The story had played itself out, and public attention had moved on to other matters. Luckily a local nobleman, the Marquis d’Apcher, organized another hunt, and in June 1767 the hunter Jean Chastel laid low the last of what had turned out to be the Beasts of the Gévaudan.

Supernatural explanations of the attacks of 1764 to 1767 continue to circulate. Even today, some believe they were the work of werewolves or meneurs de loups (magical “wolf whisperers”, or “leaders of wolves”, who can command wolves to do their bidding). But most historians now agree that the Gévaudan — a sparsely inhabited, extremely impoverished rural area — was, as Graham Robb puts it, “infested with wolves”.

You can read more about the Beast of Gévaudan in Jay M. Smith’s Monsters of the Gévaudan: The Making of a Beast and see more illustrations below.

Print showing Jeanne Jouve (AKA Jeanne Varlet), whose valiant defense of her child against the Beast made her a national heroine. She is said to have jumped on the animal’s back after it had taken her son’s head in its mouth. The child, though wrested from the jaws of death, did not survive — Source.

A German print, published in September 1764, showing various attacks and counter-attacks — Source.

Another German print published in September 1764, with an announcement in French and German of the reward offered for bringing the beast down — Source.

An oddly cheerful Danish representation by Thomas Borup of Copenhagen (1726–1770), date of publication unknown — Source.

French print, circa 1764–1765, advancing the theory that the Beast was a hyena — Source.

Jun 19, 2019