Every Society Invents the Failed Utopia it Deserves

“Now: the integration of the actual and the possible.” So speaks the radiant Marie Violette Tranchot (AKA “Octave Obdurant”) at a crucial moment in the piece that follows. Where are we? Well, we are ensconced with a cross-dressing cosmologist of all possible worlds, a scarred veteran of the age of revolution, as s/he bends, wild-haired, in unhinged service to a sociopolitical astrolabe of her own confection — call it a utopian calculator of every utopia, a clockwork orrery modeling nothing less than transcendence. John Tresch is a historian who combines tremendous learning with a luminous imagination, and he here graces us with a gift in both keys. Yes, he tips open the visionary, mechano-morphic romanticism of the mid-nineteenth-century radicals of Paris, and does so using an archival pry bar of real precision. But at the same time, he manages to vignette our vista by means of a tale so lurid and glimmering one can readily imagine it accidentally anthologized in a volume of Edgar Allan Poe. What kind of history is this? Historical fiction? Not really. Fictionalized history? That won’t do either. One is tempted to say that Tresch has here given us history as the integration of the actual and the possible. History contaminated by its subject? Yes. And to quote Violette/Octave once again: “It shows how far dreams may reach.”

— D. Graham Burnett, Series Editor

October 19, 2016

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

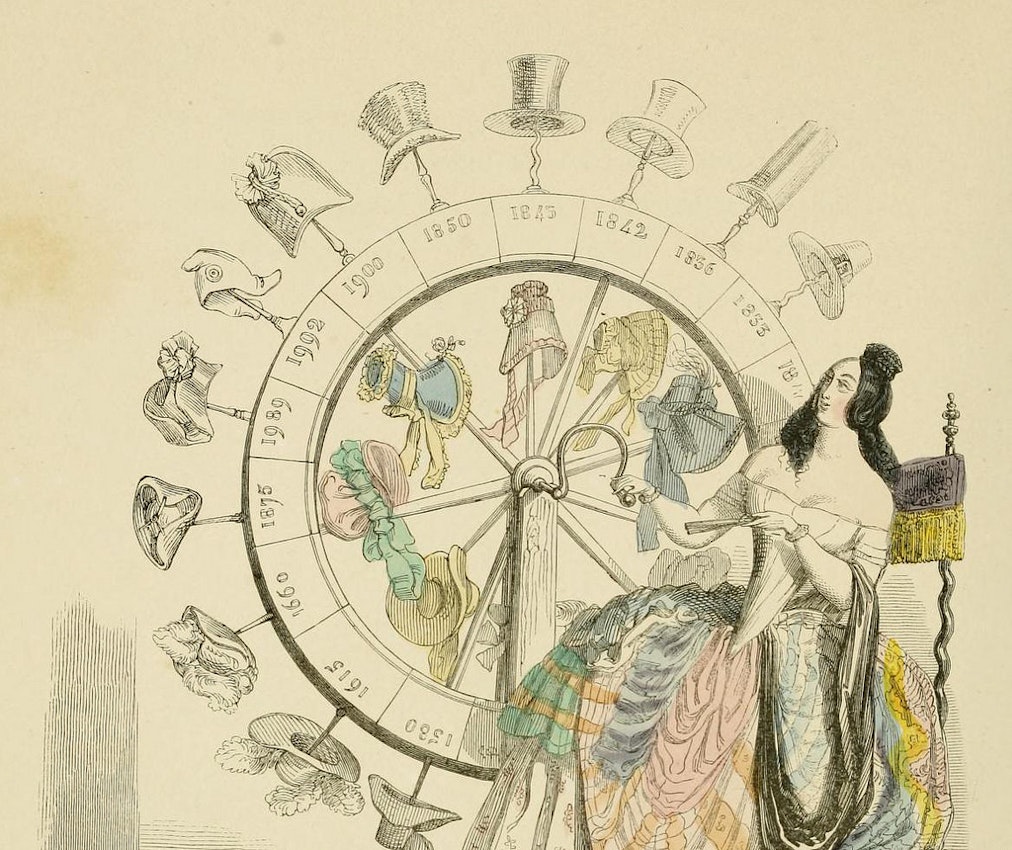

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Detail from "La Mode", an illustration from J. J. Grandville's Un Autre Monde (1844) — Source.

Let me offer a few words to introduce this translation. I stumbled upon the original, a forgotten memoir by a now legendary author, in a bound, yellowed volume of radical newspapers in Paris’ Bibliothèque Nationale. It dates from 1895, when both the past and future of the workers’ movement were rethought under the force of unrest and uncertainty. I was researching Elisée Reclus, the French anarchist geographer. “Man is nature taking consciousness of itself”, Reclus believed; the liberation of humanity and the earth went hand in hand. What Lenin called Imperialism, The Highest Stage of Capitalism, was at that time being consolidated on a global scale. Yet many fought it with new forms of thought and action; they wanted to redirect the power of new technologies, and their world-spanning reach, away from the usual endpoints of nationalist aggression and imperial subjugation. Elisée Reclus was one of those who could see a different future: “Our destiny is to reach that state of ideal perfection in which nations no longer need to be under the tutelage of a government or another nation; it is the absence of government, it is anarchy which is the highest expression of order.”1

I was looking for roots and resonances of Reclus’ science, the tools with which he saw humans helping this more-than-human destiny along. It seemed this moment from the past was ripe with anticipations and provocations for today, offering examples and other resources for those who struggle to draw new maps of politics, knowledge, nature — to remake this crowded globe.

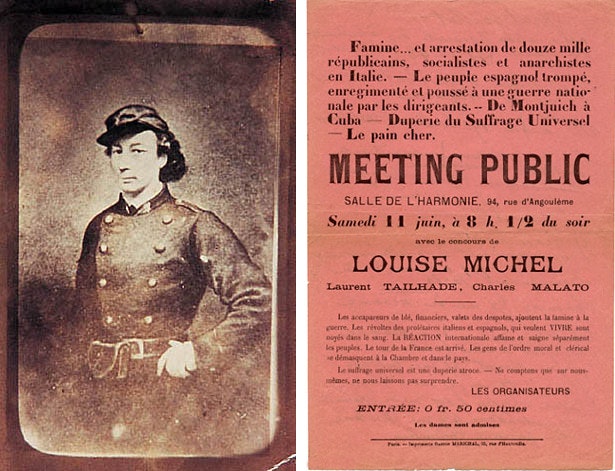

I found I had become obsessed with one of Reclus’ associates: Louise Michel. Paul Verlaine called her “The Red Virgin of Montmartre”. She was a school teacher born in 1830, a pen pal of Victor Hugo and drove an ambulance carriage for the Paris Commune in 1871.

Louise Michel was not among the 20,000 who were executed in that uprising; she served twenty months in prison, exiled to New Caledonia in the South Pacific. Amnesty was declared in 1880; she returned to France, increasingly committed to anarchism: “Power is cursed; that is why I am an anarchist”, was one of her slogans. She was arrested again and again. In prison she wrote books about “the social question”, including the astounding science fiction novels The Human Microbes and The New Era. Michel lived her last seventeen years with a bullet lodged in her skull from an assassination attempt. She also inaugurated the use of the black flag for anarchy.2

I wish I had invented Louise Michel, but she’s too extraordinary to be fictional.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, state repression and censorship made widescale political organizing difficult. New means were proposed. Some argued for “The Propaganda of the Deed”. In 1891, the anarchist Ravachol set bombs against Ministers of Public Defense, was arrested and executed. In 1893, Auguste Vaillant exploded a bomb in the Chamber of Deputies causing minor injuries. President Sadi Carnot was stabbed to death in 1894.

A result of these shocking attacks on the ruling elite was “Les Lois Scélérats”, starting in 1893. These “Scoundrel Laws” allowed draconian suppression of civil liberties: the mere mention of violent uprising landed radicals in jail.

1893 was also the year of the death of historian Hippolyte Taine, who had just finished a three volume history of France. Two years later, in 1895, the anarchist journal Le Libertaire, Journal du Mouvement Sociale was relaunched, with the assistance of La Bonne Louise.

The article I’ve translated for this essay is from the third issue of Le Libertaire. It’s signed by “Une lutteuse”, and would almost certainly have been recognized by contemporaries as the work of Louise Michel. It’s entitled: Pour en finir avec l’histoire scélérate- Le mot d’Octave Obdurant. Which I’ve translated as: Scoundrel History and Utopian Method.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Louise Michel pictured at home in her later years, around the time she is presumed to have penned the piece translated below — Source.

Scoundrel History and Utopian Method

Le Libertaire, iii, 1895, presumed Louise Michel

Who among us does not feel the shadow of fear cast by the cowardly laws of these past years? The Scoundrel Laws terrorize not only those who might commit violence, but anyone who associates with them. They reward those who denounce their brothers and sisters, sowing distrust and ill-will. They freeze our hearts and our tongues, by punishing with prison anyone who provokes, praises, or merely seeks to understand those mad acts to which an insane society has driven a few poor souls.

Perhaps even these words, here, are enough to summon our new inquisitors.

If so, I say, let them come. I know their jail cells; their guards are my comrades and friends. Scoundrel laws, like the scoundrels who created them, must one day lose their power. It is a law of justice and nature.

We who know the future, who see with certainty like a memory ahead of us the society of freedom, equality, brotherhood and sisterhood, we learn such laws from the past, even, at times, from the bourgeois chroniclers behind the walls of the Sorbonne. At the very least, from them we may learn what new tricks they employ.

Thus I recently read the three volumes of the historian whom they call “great”, Hippolyte Taine, to learn what lies were being passed off as the official past. Taine sat in a special Chair, for the History of the Revolution — a monument propped on the grave of the past like a tombstone, to guarantee that such an event will never happen again.

This historian is now himself buried, covered in praise. I come not to desecrate his memory, but merely, after so many éloges by those mindless thinkers-by-the-hour, to restore it to its true and laughable scale.

Taine tells us that history is an obscure knowledge of a distant past, and that we have nothing to expect from the future. The Revolution, this decisive overflowing of the desire for justice and a better life, is denounced as a deception, a struggle for power among upstarts, a monstrosity never to be repeated.

Among all Taine’s half-truths, fantasies, and idiocies, none is so great as his pretension to science — in which history is always a balance between race, milieu, and moment. He transforms inspired and courageous men and women into dupes of nature and of their fellows; by this he hopes to complete whatever bestialization the rulers of this society have not yet wrought.

He has created the equivalent in letters of those villainous acts of legislation. He has written l’Histoire scélérate, Scoundrel History. It shuts people’s mouths and severs their connection to the dreams, sweat, and aspirations of those who struggled before us. Scoundrel History insists on the difference between now and then, the arbitrariness of the new, the fatalism of birth, of rocks, vegetation, and rivers. In the name of science he lashes those who embraced a world more vast than his vanity.

Were these his only crimes, I would happily cast his miserable books aside — or in a more generous spirit, wrap fish in them, so that in some small way they might serve life. But I am moved to take up my pen, finally, by his third volume, which blesses the current power as good, just, and in any case inevitable. What spurs me to write is a single citation, a unique if profound mistake.

His book discusses the Commune, a glorious moment we remember by its hopes and noble example, laid low but not destroyed. In one brief passage, Taine betrays all his worship of the predictable and his denial of the unforeseen. Here we see Scoundrelism elevated to a theory.

After describing the aftermath of the Commune, the butchery of the state against the living proof that a truly egalitarian and democratic society functions well, joyously, when left to itself, he writes:

A few years later, most of this rabble had lost whatever convictions drove their violence. Even deluded demagogues renounced their youthful dreams. We need no further evidence than a pamphlet from the printing offices of confusion: Every Society Invents the Failed Utopia It Deserves, the work of a certain Octave Obdurant — a survivor of 1848, second-rate engineer and first rate rabble-rouser. This is not a wise, but a chastened work — the lament of a man awakened to the bitter truth, that only compromise and concession allow one to live with a semblance of repose. In this pamphlet, we see the renunciation of a whole generation, the inevitable calming of a degenerate revolutionary impulse. Obdurant, hard-headed though he was, at last yielded to reality; his fellow-travelers must soon enough do the same. (Histoire de la France, vol IV, Le régime contemporaine, p. 221)

Our historian has not only misread the pamphlet he cites, Every Society Creates the Failed Utopia It Deserves, by Octave Obdurant; I believe he has not even opened it.

For you see, I knew Octave Obdurant. Once, we met.

I sought the author out, in those dark years when it seemed the flame of liberty might be extinguished forever. I was moved by the memory of another pamphlet I had read in the spring of 1848. Meeting me in my youthful optimism and driving it to higher, dizzying heights, was the essay, Organize Labor, Free the Earth, signed Octave Obdurant.

It was one of the many utopias springing up like mushrooms in those days. I was under the sway of Blanqui, captivated by the burning purity of his rage. But in Obdurant there was a different persuasion: the passion of poetry, the serenity of mathematics, the earth’s conception from the first divine breath, its long slumber in chaos until at last the sons of Noah raised their heads, took up the tools of industry, and demanded a just apportionment of labor and its fruits. I was moved that Obdurant spoke also of Noah’s daughters and their high position in the earthly paradise.

This vision resembled the fantastic plenum of the Fourierists, the religious cry of the Saint-Simonians, the frenzy for order of Cabet’s Icarians. Yet in Obdurant’s words one sensed at once eagerness and reserve, a mind which had surveyed a vast territory with all the rigor of science, yet now allowed the quiet light of truth, arriving as if from the origin of time, to illuminate a holy marriage of earth and humanity, thought and deed.

There was madness to it, yes — a madness which spoke to my own. I cherished the pamphlet, even after all those utopias burst one by one like fragile bubbles blown by a child. In 1855, unwilling to abandon these honorable dreams of youth, I wrote two letters. One to Victor Hugo, the great man who repaid me with a gift I value above any other: his friendship. I wrote also to Octave Obdurant.

*

I had learned that Obdurant still lived — in exile, in silence. In Belgium. I wrote a letter, thus: Though a child in ’48, I had sworn my life to the people, and Organize Labor, Free the Earth was a clarion leading a young revolutionary through a hopeless time. I asked if we might meet.

Three months later, a reply came, written on green graph paper in a careful hand. One word: Yes, followed by a date — a fortnight hence: 15h précis.

I was filled with anticipation on the long train journey from Paris to Brussels. With only moderate difficulty I found the address: a quiet cul-de-sac in a warren of streets not yet ravaged by the projects of destruction in the city’s center. I turned the knob which rang a bell, answered by slow, heavy paces. It opened a crack, to a craggy face, peering up at me with suspicion and mockery.

I said I had come for Monsieur Obdurant. The old man took in my eager face, poor dress, cracked shoes, frayed shawl and bonnet, and spoke. “Monsieur Obdurant does not exist.” He glowered with relish.

Baffled by this sphinx’s statement, I brought out my green invitation, unfolded it, showed him the address and signature. With a slight smile he nodded, as if wondering how much of a fool I truly was. He gestured me in, pointing across the courtyard. “Third floor on the left, Mademoiselle”, he said, reminding me of my youth, my sex, my vulnerability.

With growing unease, I mounted the narrow staircase, the ceilings lower with each floor. Before a door on the third, I knocked.

A husky voice barked: “Entrez!”

Through a long, dim hallway, I followed the voice, until I reached a spare, curtained room. One empty chair stood near the entrance. Another, across the darkened space, was occupied by a slender, shadowed figure with erect posture, white hair long and flowing as in the fashion of the 1840s, in an elegant black suit, immaculate linens, a neckcloth of Persian design. A bright gaze set into a finely featured face pierced the gloom.

“Sit”, the figure commanded. As if under the influence of a powerful magnetizer, I sat without pause.

My host spoke sharply, gruffly. “Welcome, Mademoiselle. You have come to meet me, no? You wish to learn of my ideas, my thoughts. But should you not first know to whom you speak?”

I nodded.

The figure straightened. “You wrote to Octave Obdurant. This is the name with which the person before you entered the Ecole Polytechnique. It is the name on my entrance papers to the Ecole de Ponts et Chaussées. It is the name with which I signed my first articles in geometry, my first statistical tables, as well as Free the Earth, which you were kind enough to notice.”

The voice was clear and occasionally guttural; there was a warmth beneath its unyielding syllables.

“But as you have certainly realized, this is not my true name.”

I felt my mind begin to spin. I was unsure of where I was, what I was doing here, in these isolated rooms. I stammered out:

“Excuse me, Monsieur. What, then, is your name?”

“I was baptized Tranchot.” Despite the pause which followed, the name meant nothing to me until it was repeated, with its prenames before it.

“Marie Violette Tranchot.”

I was moved by an emotion of shock and recognition at once. Some part of me had already realized that I was not in the presence of a great man, but rather a great woman — no wizened brother of the struggle, but a sister. Instantly, I felt myself uncannily at home, safe at last in a place I’d never been — truly at home, perhaps, for the first time in my life. This hero, epitome of the courage and intelligence the world saw as masculine, was a woman like myself.

She must have guessed the sensation her revelation would cause. I sat in silence, collecting my thoughts, calming myself. At last I spoke; I asked to know her life and history. In an arch and formal manner, not without humor and charm, she told me her tale.

*

She was a child of the century, born in 1807 near Reims, illegitimate and unrecognized, her father a minor noble and Orleanist, a free thinker and a Field Marshall in the revolutionary Army.

He had limped home from Austerlitz, took up in secret with the daughter of a mason of the Cathedral. Marie Violette’s father, in secret, took her schooling in charge. She learned the multiplication tables by age four. She mastered Laplace and Lagrange, Greek and Latin, Descartes, Pascal, the large-hearted Jean-Jacques. When the pupil surpassed the teacher, he found a discreet polytechnician to prepare her for its examinations.

The only way forward for her was to pretend to be a boy.

Thus Marie Violette Tranchot gave way to Octave Obdurant. Even her tutor did not realize that the child with cropped hair and unbroken voice, defining quadratic functions, was a girl.

At sixteen, with Poinsot himself administering the examinations, Octave-Marie excelled her peers. She entered the Polytechnique in seventh place. She dressed and bathed in secrecy, modeling her gestures on those of older soldiers, training her voice to a manly depth. She was noticed only for the quickness of her mind and memory; at Ponts et Chaussées she became the protégeé of the great diagrammer and cartographer, Charles Minard; she was sent on mission from Metz to Lyon and Saint-Germain, designing railroads, perfecting bridges and new factories.

In Paris, through her astronomy tutor — Auguste Comte himself — she had become aware of Saint-Simon and with her classmates she attended meetings of the religion they were then pouring forth to remake the world.

A great battle was raging in her heart between her regimented life as a soldier-savant and her passions as both a woman and a republican. Suzanne Volquin and Flora Tristan proclaimed the inseparability of workers’ emancipation from that of women. Attending the Vaudeville one night she observed George Sand, dressed as a man but hiding none of her femininity; Octave-Violette was thrilled by her courage and her words.

At last, to Claire Bazard, the Saint-Simonian priestess, Octave-Violette revealed her torments. Bazard knew and understood all; even the Père Enfantin acknowledged her and praised her “sublime versatility, symbol of the androgynous divine.” She became one of the sect’s most persuasive preachers; she shared their collective house, took on lovers, and terrified her former classmates by appearing alternately as Octave and as Violette.

After the Saint-Simonians were scattered, the Père and his loyal Chevalier imprisoned, it was with a troop of Fourierist colonists that Violette found herself in Algeria in 1836, attempting to set up a phalanstery in the foothills of the Atlas Mountains. Writing as Obdurant she examined and documented the Agricultural Science of the Berbers; she scoured the Qur’an, undertook study with a marabout Sheikh.

“He sent me dreams”, she said sternly. “Maps of paradise.”

I dared not to ask what bejeweled landscapes and labyrinths she explored with her Sheikh; it was evident that this was some holy secret she would either take to the grave, or announce at a moment reckoned by an unknown astronomy, and with it set the world aflame.

She was back in Paris by the 40s, her engineering expertise always much in demand. She wept at the tomb of mathematician Sophie Germain, protegée of Lagrange and Joseph Fourier. She taught geometry to weavers and broke bread with republican journalists and polemicists. Half a lifetime of secrecy had taught her to keep quiet, but when the hour grew late, she joined their disquisitions and disputations over the form of artificial paradises to come.

“I ran circles around them”, she said, proud and contemptuous. “They spun only clouds and moon beams. Whereas I had learned to dream in stone and steel.”

During a season she spent in Leroux and Sand’s experimental commune, she arrived at the formulas of Organize Labor, Free the Earth, which had so stirred my imagination. Though she did not realize it, she was preparing for 1848. When it exploded, she was the first to the barricades.

“Four months of intoxication”, she described it, “followed by a hangover without end.” In the June Days, she spent weeks in prison. She later signed articles denouncing both the untethered utopianism of her fellows and the opportunism of her enemies. With Bonaparte’s coup of 1851 she fled, exhausted by hope.

In Brussels she said she had been laboring, for years now, on a new project, a “return to first principles”. Apparently this required utter solitude; I saw nothing in her rooms to indicate any friend, lover, family, or any other visitor but myself.

*

Octave-Violette then expounded her philosophy — like a canal whose gates were suddenly opened, releasing a cascade driven by impatient gravity. I did not understand all she said, though I later recognized it as the method in her pamphlet on utopias.

“To understand the future, we study the past”, she said. “We know the past best by the future it dreams.”

In long historical investigations she saw wave after wave of starry-eyed youngsters, each of them certain that they at last had found the true solution to the problem of human existence. At first she saw only monotony in these relentlessly repeated and doomed burlesques of abundance or simplicity. She began to wonder about hidden variables, about the law connecting real conditions and the wild scenarios to which they gave birth.

She found a guiding thread which became her title: Every Society Invents the Failed Utopia it Deserves. Whether this was a discovery, or an a priori determination, remains to me obscure. Revising Leibniz, she saw an undeniable metaphysical necessity regulating what is, what might be, and the gap between them. She set herself the task of defining and reckoning that gap.

“The reach of a society’s dreams”, she said, “always exceeds its grasp. The measure of this excess — the degree by which a utopia fails, the area between the curves of reality and aspiration — is a periodic function, a law of history. Once known, this formula is the philosopher’s stone of the politician and the revolutionary.

“To discover it requires us to establish the relationship between what is given, what is dreamed, and what is needed. The given is easily observed. To learn what was dreamed it suffices to read the forward-looking testaments of speculators. It is the real historical need which is most difficult to ascertain. Our political economists believe the contrary: either that human needs are set and knowable, or that they are endless.

“Neither is true”, she said. “Need is a historical variable. It changes as a function of the relationship between the givens of natural and social reality, and available visions of a better world. The method of utopia consists of establishing this relationship, making predictions, and acting upon them.”

She peered inquisitively into my face. “You think I speak in riddles.”

Frightened, I said nothing.

“These are no mere words, but the results of a rigorous science”, she stated imperiously. I blinked at her, not knowing what she wanted.

She sprung up suddenly, with youthful speed: “Come, I will show you.” She strode past me, her boot-heels clicking down the hall. I followed a few cautious paces behind. Before a closed door, she took a key from her trousers and unlocked it, looked back at me, opened the door and walked through.

I followed her into a workshop whose floor was covered in scraps of wood and metal. A small furnace stood in the corner, near tongs, hammers, an anvil. Wan rays of late afternoon sunlight streamed through the gap of heavy curtains. One wall was covered in slate, scrawled with a hieroglyphic blizzard of diagrams and numbers. On an overcharged bookshelf I recognized Proudhon, texts in Arabic and Chinese, Schiller’s Letters, a volume of Dante.

In the center was a large round drum, with scraps of cloth, metal, and wood nailed into its sides. Viollette-Octave leaned over this object like a vintner proud of her harvest, an architect above the blueprint of a new world.

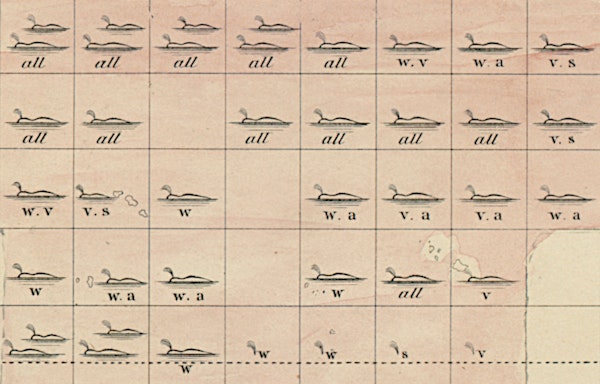

“Behold. My Conducteur à Comparaisons Cosmographiques.”3

It was a sublime contraption: a wooden cylinder, over one meter across. At its center stood a slim but sturdy pole; in its interior was a smaller ring. Between the two rings was rumpled green velvet, calling to mind a roulette wheel as much as a model solar system.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.A Philosopher Lecturing on the Orrery by

Joseph Wright of Derby, ca. 1766 — Source.

The bottom of this well was painted in gold, crossed by elastic ribbons in red, attached to tiny hooks on the inner wooden ring. These divided the space into segments like irregular slices of a tart or the spokes of a warped carriage wheel. The outer circle was covered in brass, hatched out in degrees; at one side a metal arm like a slide rule reached into the center, immediately displaying the radius. On the front was a glass-covered dial whose needle pointed to two.

I had no words. She said, “This is merely a model. But the principle should already be clear.”

It was not. She began to show and to tell.

Turning a crank on the right of the device, the inner ring drew toward the center. “The golden disk at the bottom is the germinal base of beatitude. Its size varies with each era.” She turned the crank in the opposite direction, and the ring expanded outward, exposing more of the gold, pressing the green velvet together and stretching the red bands.

“Look closely. These ribbons cut out nine segments — the nearly perfect number: a square, a triangle of triangles, not yet the stability of ten. These are the nine springs of our nature.” She listed: “Material comfort, equality, justice, desire for command, desire for submission, comfort of stasis, power of flight, butterfly of change, and finally,” she raised her eyebrows, “beauty.”

She owed a debt to Fourier’s keyboard of the passions, she admitted. Yet rather than human motors, her nine sections were “actual quantities of valued entities, goods in the most general sense.”

To establish this “base of beatitude”, is the first, easiest task of the utopian method, she said. Estimates could be derived from evidence in taxation records, agricultural and geological surveys, weather reports, marriage laws, artistic outputs, the state of the sciences and arts, words used in obituaries and their frequency. She was impatient with this inventory, as though one might become embroiled in its imperfections, rather than grasp what she called “the parallax between the pardonable generalization and the exceptional particular which yields the conditions of existence”. It was a simple matter of applying the principles of descriptive geometry and natural history to the human species. “All this detritus of the past — Collect it, count it. Then move on!"

“Our modern Political Economy is concerned almost exclusively with whether the base of beatitude is increasing, declining, or simply waxing and waning according to a cycle as regular as that of our moon. Of course, applying the Cosmographic Comparator to the successive eras of humanity would provide an indisputable answer to this question.

“Yet this is laughably small fruit in light of the device’s true potential.” She pointed to the red elastic bands across the center. “Here we see traced the distribution of the given. The proportions and relations claimed by each of the goods shifts with each era. Regardez.”

She unhooked the bands around the ring, stretching and bending them, rehooking them to divide the tart into different shapes. “The comfort of stability gives way to a rising love of flight; once bread and shelter attain a certain dimension, the share of beauty, by a natural compensation, immediately begins to grow.” With each phrase and new adjustment, the pie pieces shifted. “The desire for command expands, drowning out justice, and occluding the sliver of equality. Desire for flight shrinks near to zero, and comfort in stasis threatens to overtake the whole left half.”

“Do you recognize it?” She gestured with her chin at the new configuration, waiting for me to answer. I did not. “The Empire of China, at the time of Marco Polo!”

She spoke in professorial tones. “Now we can at last truly see, with an exactitude unimagined by the statisticians, the provisions of earth, social order, and human happiness across history.” I saw she expected me to nod. I did, though without comprehension.

“But the Cosmographic Comparator comes into its own when we add the final piece. I cannot tell you the sweat and pain this cost me.”

She turned to open a curtain behind her, letting in rays of thick golden sunlight and revealing a wide cabinet out of which she lifted a bulky, lustrous metal object, and heaved it forward for my inspection. It was a round metal grill, a disk raised at its center like a cymbal, woven of multiple strips of brass in various widths and lengths.

“This is the speculative crown, the utopian umbrella.” With a grunt, brushing aside my gesture of assistance, she balanced it on top of the spike at the center, and spun it around several times; it slowly lowered itself until it stopped, lodged snugly in place.

It covered the cylinder below it, like an awning with gaps, showing the pattern of gold and red beneath.

Reaching to grasp a knob, one at the crown’s center and one at its edge, Octave-Violette said, “The umbrella can be adjusted to render any possible inventory of society’s goods. This concrete utopia reflects, with modification, the germinal base, the pattern of goods below.

“It’s first decisive variable is the distribution of the possible.” She loosened the screw at the top, letting the metal bands slide together and apart, closing and opening gaps which wove into stars, spirals, compass roses, fleurs de lis, in undulating, mesmerizing forms.

She snapped her fingers, waking me from my reverie.

“The second variable is the diameter. It shows how far dreams may reach.” With a twist of the knob on the edge, the disk flared out from the center; twisting in the other direction, it drew inward. “By comparing this distance to that of the germinal base below, we get the age’s disgruntlement index.”4

She gave a quick inspection, murmuring, “And now to calibrate.” Below the dial, she pressed a button; the needle dropped to zero.

“Now: the integration of the actual and the possible.” Opening a divided drawer, she selected out a number of purple elastic bands, with hooks on either end. She laid them out on the palm of her hand, like fishing lures. “The compensation vectors.”

Kneeling, reaching under the crown like a piano tuner, she latched the purple bands onto hooks hidden beneath the umbrella, then looped them, one by one, at precise locations on the red elastic bands.

“Watch the dial!” Its needle rose minutely with each strand she added. “It measures the tension between the germinal base and the distribution of the possible — the total force on the system.”

She hooked the last into place, plucked out a high, clear note. “This gives us the plausibility factor, from one to ten — Ten is ‘Inevitable’; seven means ‘nothing to lose’, five is ‘possibly maybe’, four ‘probably not’, three ‘snowball’s chance’, two ‘bazonkers’, down to one ‘absofuckinglutely never on your life’. The number is the integration of actual conditions with people’s hungry imaginings, and the tension between them. It tells us how fast, and with what violence, a given utopian design is destined to fail.

“A rigorously demonstrated function relates the plausibility coefficient, the germinal base, and the disgruntlement index; from it, we obtain the historical need for any moment.” Her voice was rising in volume, her gestures growing more agitated.

“Performing this same operation for successive eras and the incomplete utopias they generate, in a principle of sufficient unreason, we line up a series of values, ascending and descending. We can then trace the vector of historical need and the vector of realizability from one era to the next. The relation between these functions, ascending and descending, allows us to analyze, at any moment in the past, present, or future, which utopia has the greatest likelihood of failure at any given moment. The point at which these curves cross is the moment in which to act. This is the goal toward which all the philosophers have striven. These curves are nothing less than the signature of God and Nature, written across the ages, from the first imprinted fiat to the final apocalyptic flourish. You see?”

She spoke impatiently, breathing fast, her face beginning to glow with both her own agitation and the late sunlight of the setting sun streaming through the curtains cracked open behind her. Ashamed in the face of this profound learning to feel myself such a poor pupil, I ventured a simple request. “Perhaps if you gave an example...”

“An example?” She stared as if possessed. “You want an example?” Arms outstretched, as if to dive into her machine, she cried: “I will give you the past two thousand years — for example!”

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

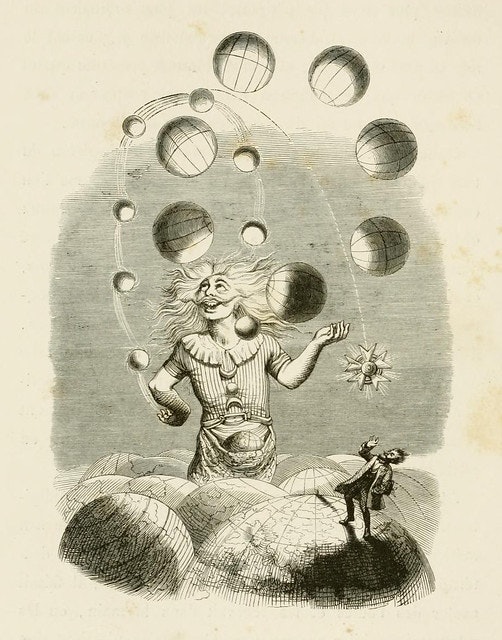

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Untitled illustration, showing a juggler of worlds, from J. J. Grandville's Un Autre Monde (1844) — Source.

She turned the crank; with a shriek that made me shudder, the inner ring contracted, leaving only a small golden disk. She restrung the red bands and adjusted the spokes. Her hands were a blur as she pointed out proportions.

“This, you recognize, is Ancient Greece. A rough land with simple satisfactions. A relatively equal distribution, haunted by material scarcity, political instability, the deadly constriction of slavery."

She twisted the umbrella into a small, tight form. “Now here is the first dream of golden ages, in Pindar and Virgil, looking backwards in escapism to livestock born tame, to crops that needed no coaxing.” She strummed the bands, pointed to the dial, now at three. “Childish compensation for the pains of agriculture.”

She adjusted again, expanded the golden disk, reshaped the umbrella until a triangle appeared. Pointing out new figures she rattled off: “Iron, colonial expansion, democratic experiments, the knots of the helots. The speculative crown, of course, is Plato’s Republic: his caste system, sprung up from the Peloponnesian Wars. As an ineluctable necessity this vision of Spartan austerity emerged, justifying in an ideal order behind the world. The birth of mathematics and political fantasy, in a single gesture.”

She adjusted the radius below and the metal shade above. With a practiced hand, she again reworked the pattern of bindings. “Rome. Harmony of law. Roads. Grain. Straining under excessive expansion.” She flicked the umbrella, which whirled until it stopped in the form of a rose. “Now, the Kingdom of God, Jesus of Nazareth. You see the coefficient, nearing one? Almost as if that was the whole point: to thrust the promised land of the Hebrews into the eternal beyond. Look at this disgruntlement index! Off the chart! No going back after this. The gap between hic et nunc and the unattainable. Setting humans running — and with what unholy tension! — toward the horizon of an unreachable plane.”

Eyes flashing, she cranked the walls in closer, thinned out the profile of the crown. “And now, Augustine’s City of God, hovering above the slack uncertainties of the late empire, the spent energy of past glories, a decadent nobility and an implausible polytheism, now restrung with the longing for a simple solution. An endless mortal pilgrimage rewarded with the only true Eternal City — one outside the world.”

Again she twisted screws, hooked and unhooked. “A shrinking, now, of the givens — the long dark ages — and here, in the overextended fantasies of the Land of Cockaigne — mais quelle grogne! — the projection of vast hunger and want: fill my belly and I want for nothing.” To harmonic twangs, she returned. “Now note, one by one, the utopias drawn up under the strain of the monastic orders. Here Benedict; now loosened into the tender joys of Francis.

“Something is stirring in these monasteries, where utopia and reality live in such proximity. The base of beatitude becomes itself a utopia. The plausibility coefficient runs high here, nearly eight; indeed, even in their obvious imperfections, the orders lasted centuries!”

She plunged, again, beneath the umbrella; broken red bands sprung out of the tub as she grasped across the table next to her for replacements. Her voice was muffled but relentless. “Vatican opulence blocks the higher view. Regal powers of Europe inflate in petulance.” She appeared again, pointing at the dial. “Watch the plausibility!” The needle, drifting back to three, jumped to seven.

“The continents of the New World appear in the spyglass. The science of cosmographic comparison enters its adolescence.” The umbrella assumed a beautiful form, an iris blooming against a chaos of red below. “Surely you recognize this? The land of Utopia, properly named by Thomas More. In its frank earthly paradise, the template for all future dreams. See how closely the diameters align! Little would be needed to bring it about materially — Yet see how violent its strain here — what enormous intellectual, spiritual, political upheaval it would require!

“Note also the similarity, here, here, and here, with the diagram of Benedict: More, aligned with Luther and Calvin, lets the monastery loose upon the world. Indeed, this next crown, from the Dominican Campanella with his City of the Sun” — the umbrella took the form of seven concentric circles — “the world itself becomes a well-furnished monastery. Readjust slightly, remove the wallpaper, and strengthen the part of equality — Here it’s Winstanley and the Levellers. An elegant pattern, no? But I get ahead of myself. As for Lord Bacon,” crouching energetically, she knotted and reknotted strands of red and violet, “here I add the will to technological power, here, the love of royal pomp, and there a maritime fantasy of becoming Beefsteak Conquistadors — and voilà! New Atlantis in the Age of Elizabeth! The Don Quixote of imperial ambition, agricultural improvement, and small machines!”

She took a breath, her white hair wildly uncoiffed, her neckerchief hanging loosely. “I could spend hours with you here on the upside-down worlds of the seventeenth century and those of the eighteenth — Mercier and Condorcet, the great Babeuf.” She gestured around the machine. “Here is where the Encyclopédie would stretch the restless share of learning, here the philosophes deny the heart, the Jacobins lay down a formal but not yet a felt equality.

“Yet even so, the way is being prepared, for our noisy, staggering age.” She crouched again, gave the crank a mighty twist. Like a steam train approaching from the distance, a high-pitched metal whine began from within the machine.

She gasped with exertion as she restrung the vertical strings. They pulled the umbrella downward.

“See here the panorama: the growth of productive powers, the economic and martial entwinement of the world into a single system, the conscious rise of labor and the workers, both below and above.

“Look, here, one republic of workers across the globe! And here! An end to tyranny! There, perfected agriculture! The realization of universal association!”

A great groan arose from the wooden walls of the cylinder. She looked at me, eyes lit with frenzy.

“How far we have traveled, no? One more push and we stretch the crown to where its edge at last matches that of the germinal base: a dissatisfaction index of zero. And here” — she twisted, then pointed to the dial, trembling just above nine— “we would at last reach ten — perfect plausibility — here, at last, action will be the sister of the dream!” She was gripped with a steely intensity.

“One last step remains. Now, we must read the instrument backward — we decode, from this perfected configuration, the precise utopian utterance and image which is required, to bring its own world into existence.”

In the setting sun the machine’s tangle of spikes and strings cast otherworldy shadows across the room.

Looking proudly into my eyes, she said: “It was all so simple, once I saw.”

My admiration had turned first to awe, and now to terror. The sage before me, digging in the mines of the past, climbing the fairytale turrets of the future, had lost her foothold in the present.

The metal shriek grew louder with a sound like a bursting spring. I muttered a hasty excuse, backing toward the door, the machine’s ominous patterns spinning around the room in dizzying reflections. Octave-Violette, lost a thousand years ahead and behind the moment we shared, started at me with a ragged, eternal desperation. With a growl like a pained animal, reaching a long thin hand toward me she cried: “My dear, you’ve seen nothing yet! You must stay here, return to Paris tomorrow!”

Part of me longed to take her hand, to allow myself to be consumed right along with her in the fire of her obsession. But some other impulse made me shake my head, backing out of the workshop, away from the grip of her eyes, the now-piercing shriek, the creaks and knocks of wood and metal the machine was letting out. As I hastened down the hallway, she called out:

“Remember, child! Everything dies — that is a fact. But all that dies — one day comes back!”5

I hurried through the door, singed by the fire of certainty which possessed her, like that mad alchemist who returned from his glimpse of the absolute unable to report what he’d seen. I stepped quickly down the staircase, past the room of the porter in which a single candle flickered. I hurried out into the street, into the familiar darkness of the nineteenth century. Pulling on my bonnet, drawing the shawl around my shoulders, I swiftly retraced my steps back to the railroad station, without a glance behind.

*

To tell the truth I still cannot say if there was more of genius or lunacy to the being I came to think of as the Violet Sister.

I later heard rumors about the androgynous geometer. From Belgium she went to London and Manchester, giving lectures before setting sail to America. She visited Oneida, New Harmony, fixed barrels at the ruins of Brook Farm, sailed to Nouvelle Orleans where, in the Western valley of the Mississippi, she disembarked for several years at a former plantation run by former slaves on principles laid down by Fourier, Cabet, and Mohammed.

From there, the record grows sparse. She was spotted in Nicaragua, organizing the Mayan opposition to the Yankee, Walker; later it appears she took up residence in Panama, with a plan she described as “snipping the umbilical of the globe”.

In 1871, still on that fateful isthmus, she received news of the Commune. I can only assume her calculations had convinced her that the hour had arrived. She was on a ship to France within days. Was it foolish for a woman nearing seventy, halfway across the world, to do anything but wait patiently to hear how things turned out? But Violette measured wisdom and foolishness by a different compass than others.

Yet she made it only as far as the Spanish border. She was stopped at Pau, her papers questioned, told she would have to wait a week. Anxious to witness the new society being born in Paris, she sought some other route; she died in the hands of the border police.

These last rumors were told to me by a wild-eyed poet and drinker of absinthe who claimed to be her abandoned son, whom I met a few years ago at a café in Ménilmontant. Believing that she was carrying his inheritance, as well as plans for the perfected Cosmographic Comparator, he said he had retraced her steps from Pau to Bogota and back. He found nothing concrete. Now he himself has disappeared, leaving only a poem, “Barjot de Belleville”, in a nihilist journal, Le point final.

Octave’s second pamphlet appeared in the 1860s; I stumbled upon a copy in a reading room not long after it was published, on a block now razed to the ground to make way for one of Haussmann’s boulevards. I read it in one sitting with equal parts fascination and confusion. I was pleased to recognize and remember expressions she had used in our one meeting, and felt both admiration and sadness for the author, who had lived such disappointment and denial her whole life, upright in the truth she believed she had found, yet whose hopes for a future society had closed her off from the world.

I return to Taine, that Scoundrel of Historical Studies, recently buried, who so abused the testament of the Violet Sister, trying to make it one more coffin plank for the eternal revolution.

Whatever this document was, Every Society Invents the Failed Utopia It Deserves, it was not a cry of despair. Or not only a cry of despair. It was charged with hope and learning. And while Marx, Engels, and their followers expelled Bakunin and denied their own ingenious precursors, by opposing their supposed scientific socialism to a utopian one, Octave-Violette knew the two were inseparable: that a history without utopia is dead in spirit and fact, but that the future cannot live on dreams alone; that any science worthy of the name has no other purpose than the visionary improvement of life on earth.

Even in her greatest obscurity, the Violet Sister drew toward revelations which cannot be separated from lucid exactitude. Her essay ended thus:

When the vectors balance in stasis, when the distances cancel out, when the needle returns to the originary perfection of zero — then, with recollection and anticipation yielding to what surrounds us, we will have found a center of our universe at last beyond compare. The unveiling of heaven while in hell. The dream inseparable from the suffering which gave it life. Know this once, and there is nothing left to know.

I do not claim to understand all that the Violet Sister wrote, all the prophecies she declaimed. I seek only to redeem her memory from the backward-looking certainty of scoundrels. I wish for the world to see her as I knew her once, and I dare to hope, even as my own star dims, that her history may be one more beacon leading us forward, to the bright future we must see ahead.

Une lutteuse, 1895.

John Tresch is Professor and Mellon Chair in History of Art, Science, and Folk Practice at the Warburg Institute. His books include The Romantic Machine: Utopian Science and Technology after Napoleon, which won the 2013 Pfizer Prize from the History of Science Society, The Reason for the Darkness of the Night: Edgar Allan Poe and the Forging of American Science (2021), and Cosmograms: How to Do Things with Worlds (forthcoming from University of Chicago Press).

![[*Door creaks open. Footsteps*]: Fredric Jameson’s Seminar on *Aesthetic Theory*](https://the-public-domain-review.imgix.net/essays/mimesis-expression-construction/5448914830_cc288c2266_o.jpg?w=600&h=1200)

[Door creaks open. Footsteps]: Fredric Jameson’s Seminar on Aesthetic Theory

By meticulously translating his recordings of Jameson’s seminars into the theatrical idiom of the stage script, Octavian Esanu asks, playfully and tenderly, if we can see pedagogy as performance? Teaching and learning, about art — as a work of art? more

Chaos Bewitched: Moby-Dick and AI

Eigil zu Tage-Ravn asks a GTP-3-driven AI system for help in the interpretation of a key scene in Moby-Dick (1851). Do androids dream of electric whales? more

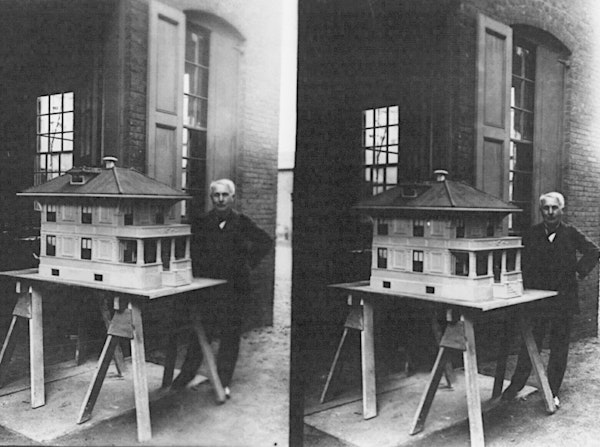

Concrete Poetry: Thomas Edison and the Almost-Built World

The architect and historian Anthony Acciavatti uses a real (but mostly forgotten) patent to conjure a world that could have been. more

In the affecting work of sensory history, Peter Schmidt uses the “strikethrough” as a kind of shadow-writing: his “Encyclopedia of Light” reveals little dark threads of undoing — marks of the second thought that endlessly cancels the first. more

Brad Fox tells a history-story that pulls on a life-thread in the tangle of things. But that only makes it all a little knottier, no? more

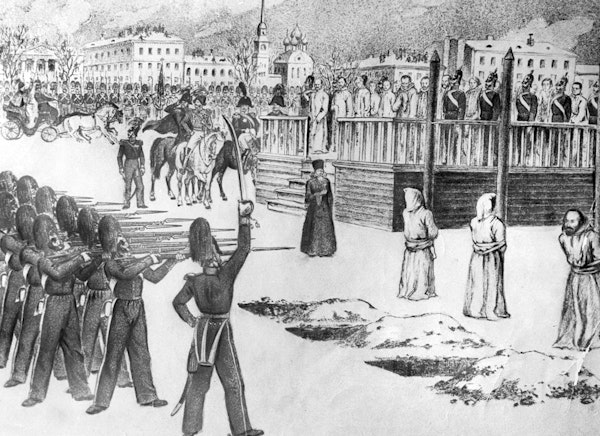

A second life? To live again? Fyodor Dostoevsky survived the uncanny pantomime of his own execution to be “reborn into a new form”. Here Alex Christofi gives these very words a kind of second life, stitching primary source excerpts into a “reconstructed memoir” — the memoir that Dostoevsky himself never wrote. more

In this affecting photo-essay, Federica Soletta invites us to sit with her awhile on the American porch. more

.jpg?w=600&h=1200)

At the intersection of surfing and medieval cathedrals, from the contents of a suitcase, Melissa McCarthy stages a plot that walks its way across paranoia, language, and the pursuit of knowledge. more

Food Pasts, Food Futures: The Culinary History of COVID-19

A criti-fictional course-syllabus from the year 2070 — a bibliographical meteor from the other side of a “Remote Revolution”. more

Titiba and the Invention of the Unknown

In this lyrical essay on a difficult and painful topic, the poet Kathryn Nuernberger works to defy history’s commitment to distance, to unsettling effect. more

In Praise of Halvings: Hidden Histories of Japan Excavated by Dr D. Fenberger

Roger McDonald on the mysterious Dr Daniel Fenberger and his investigations into an archive known as “The Book of Halved Things". more

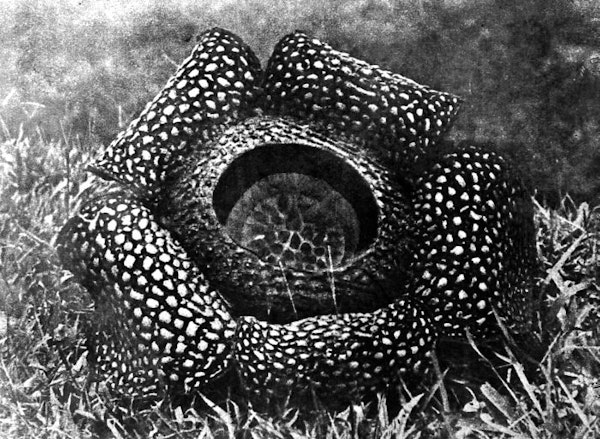

Weaving extracts from a naturalist’s private journals and unpublished sci-fi tale, Elaine Ayers creates a single story of loneliness and scientific longing. more

Remembering Roy Gold, Who was Not Excessively Interested in Books

Nicholas Jeeves takes us on a turn through a Borgesian library of defacements. more

Kant in Sumatra? The Third Critique and the cosmologies of Melanesia? Justin E. H. Smith with an intricate tale of old texts lost and recovered, and the strange worlds revealed in a typesetter's error. more

Lover of the Strange, Sympathizer of the Rude, Barbarianologist of the Farthest Peripheries

Winnie Wong brings us a short biography of the Chinese curioso Pan Youxun (1745-1780). At issue? Hubris, hegemony, and global art history. more

The Elizabeths: Elemental Historians

Carla Nappi conjures a dreamscape from four archival fragments — four oblique references to women named “Elizabeth” who lived on the watershed of the 16th and 17th centuries. more

Dominic Pettman, through the voice of a distant descendant of the Roomba, offers a glimpse into the historiographical revenge of our enslaved devices. more

In Search of the Third Bird: Kenneth Morris and the Three Unusual Arts

Easter McCraney explores the ornithological intrigues lurking in an early-20th-century Theosophical journal. more